Hands On: XCOM 2’s Brutal Difficulty And Superb Tactical Overhaul

Nobody gets left behind. That was my XCOM: Enemy Unknown rule and it was a rule that I adhered to in almost every one of the hundreds of missions I oversaw. If a squad fell in combat, they fell side by side.

XCOM 2 [official site] has made me break my one rule. Repeatedly. Deviously. Tragically. It’s hard as nails, and superbly distorts the tactics and strategies that were successful in its predecessor. I’m smitten.

I received a preview build of XCOM 2 just before Christmas and I’ve spent almost as much time with over the last two weeks as I have with all of the family and friends added together. Making a mockery of the idea of a winter break from the game criticism beat, it’s been my near-constant companion. That in itself should tell you something about how much I’ve been enjoying it, as should

my previous words on the subject.

There’s so much more to tell though. I don’t want to spill the details about all of the new and exciting things though because you deserve to discover them for yourself. With its varied mission types, new foes and winding strategic structure, XCOM 2 puts the Unknown back in the series and that’s the way it should be.

In the three campaigns that I’ve started (and finished; the version I’m playing does have a cut-off point but I’ve failed rather than reaching it), I’ve faced more objectives than in every complete playthrough of Enemy Unknown and Within put together, and I’ve developed an entirely new tactical mindset.

That’s what I’m going to focus on here – the tension and terror of the tactical side of XCOM 2. When I first played the game, in a brief session at a preview event, I was surprised by the apparent depth of the strategic map. A closer look suggests that depth might not be quite the right word: unpredictability is closer.

Gone is the steady and structured escalation of the invasion, and gone are the boring bastard satellites that were to the campaign’s shape what weights and other hindrances were to Harrison Bergeron. Freed from the single-route linear progression, XCOM 2 presents an alien menace that reacts and builds power, through visible facilities in the world, and through a Doomsday counter that can be interrupted and set back by the player. There’s more, in the form of side missions and alien activity directed toward objectives other than an apocalyptic end-goal.

I’ll analyse all of that more carefully when I have the full game in my mitts. There’s loads to say about the actual missions as well, you see. They’re even more surprising than the changes to the Geoscape and the entire alien occupation storyline.

Above all else, XCOM 2 is a game of surprises, which is (ironically?) precisely what I didn’t expect it to be. It builds on the foundation laid by Enemy Unknown but distorts and challenges your expectations and understanding of that game at almost every turn.

The most obvious example of that tendency that I’ve seen occurs during an encounter with something new. That ‘something new’ disrupts the battlefield, forcing a rethink regarding the importance and utility of the usual movement from cover to cover. It makes a mockery of the good practice you’ve drilled into your soldiers and that will likely cause you to lose a squad or two as you readjust.

What’s truly brilliant about the execution of these twists in the tale is the way that they’re introduced. Although times have changed and XCOM are now a guerrilla resistance operation striking against an occupying force rather than a sanctioned defense force attempting to repel an invasion, many of the plot beats in XCOM 2 have direct analogues in Enemy Unknown. There’s a familiarity to the research path that initially makes the game seem like it’s going to mirror the original, in the way that Terror From The Deep found its own brand of terror missions and alien containment facilities.

Those analogues do exist but Firaxis make every effort to subvert the structure at every turn. That’s true in the day-to-day operations of XCOM, who are now called on to abduct high-ranking officials rather than to prevent abductions, and it’s true in the turn-by-turn catastrophes on the randomised tactical maps.

They look spectacular, those maps. Almost every object and building works not only as a block of potential cover on the battlefield but as a signpost to the events between the two games. There are optional backstory voiceovers, which trigger when you see certain environmental features for the first time, causing one of your chums to break radio silence so that they can fill in the details of the world for you. While there’s a lot more of that this time around – your crew have as much to say for themselves as party members in an RPG – the environment contains all the clues and evidence you need to piece things together. It’s a masterclass of environmental storytelling, and the images of your custom-designed operatives as wanted terrorists that flash up on in-world billboards and checkpoints are the icing on a delicious cake.

The randomisation of the maps works as well as I’d hoped as well. The repetitive maps of Enemy Unknown were one of the few black marks against it. Here, not only does the slotting together of structures and outdoor tiles make for exciting variety and unpredictability (that word again), it never seems to throw out an incoherent jumble. There’s a much better flow to the missions, which have aliens patrolling credible routes and gaggles of civilians watching from the sidelines as all hell breaks loose.

And that brings me to the objectives of those missions. I’ll be astonished if the full game somehow fails to live up to these early hours but whatever its achievements, the seemingly simple act of redesigning mission objectives might be the most important change of them all. When your squad land in a combat zone, they’re often concealed and

I already suspected that mechanic would work extremely well – what I didn’t suspect was the brutality and necessary compromises that this new mode of warfare would bring about.

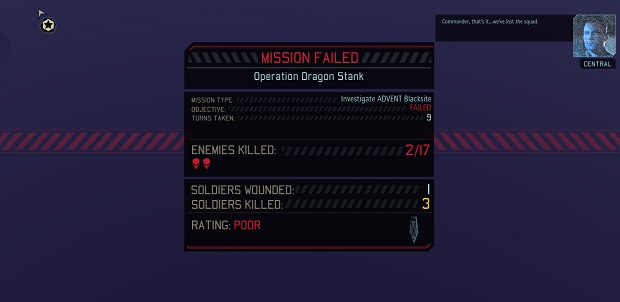

Everything is rooted in the difficulty level. Playing on the normal setting, I’ve found the game far more difficult than XCOM: Enemy Within on veteran. In that game, I’d fallen into the habit of considering a mission a failure if I didn’t return with a full complement of operatives. In XCOM 2, I’ve whooped with delight when a single soldier manages to limp back to the extraction zone (and they really do limp, stagger and slump on the mission debrief screens, as well as suffering from the long-term psychological effects of the war).

At first, I thought the game might be

too difficult, with spikes that seemed to require grinding for resources to overcome, but I’m becoming convinced that I was thinking about my approach all wrong. If an objective calls for the destruction of a specific object or facility on the map, it’s sometimes necessary to use two squad members as a decoy, drawing aliens away from the target, while others get the job done. Those decoys are expendable.

Dying for the cause is often the only way to advance the cause and, hideously, I find myself totting up the resource costs to replace sacrificed soldiers against the benefits of a successful mission that requires their sacrifice. The future of humanity is at stake, after all.

I’ve found myself ordering soldiers to flee across city blocks in an attempt to get back to the evac zone while a sniper stays in place on a rooftop trying to take down pursuing enemies, knowing that she’s cut off from escape. The existence of objectives that encourage extreme risk-taking and that require the maintenance of a safe route back to the evac zone creates unfamiliar situations and outcomes.

With my new ruthless tactics, I’m enjoying more success but even my victories often look like failures as I throw more rookies into the meatgrinder. I’ve navigated the difficulty spikes by ditching familiar tactics and standard measurements of success, and learning to think like a desperate resistance leader rather than the commander of an organised military unit.

Aside from the possibility that the mid- and end-game really might be too punishing, with no sense of the tables turning in XCOM’s favour and backs permanently against walls, I have few quibbles. Loading times for missions are a little long and you’ll become familiar with the twitchy animations of your operatives as they sit in the Skyranger preparing for action, and though the cameras are improved, there are times when a dramatic moment is somewhat spoiled by a wall obstructing the view. Those things might be improved before release but even if they’re not, they’ll be cause for minor complaints given the quality of the game as a whole.

I’d love to rave about the new enemies and how they fit so effectively with all of the tactical and strategic changes mentioned above, and there are moments, scripted and otherwise, that I’m bursting to discuss. In fact,

I haven’t felt like this about a game since 2012 when I wrote: “No coy introduction here; XCOM is marvellous and now that I’m not playing it, all I want to do is talk about it, write about it, and jump up and down hollering about it.”

Well, no coy conclusion here. XCOM 2 is marvellous and I’m sorely tempted to jump up and down hollering about it. Back in 2012 that was as much due to a sense of relief that Firaxis hadn’t made a mistake in attempting to revive the license at all – this time it’s because they’ve built on a strong foundation intelligently, and with an unexpected degree of cunning. The occupation storyline is more than a new flavour, it’s the base on which the game’s themes, tactics and strategies are built, and this war doesn’t feel like a rehash – it feels like a voyage into the unknown.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)