RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Leonard Boyarsky on Fallout, Interplay and Troika

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Leonard Boyarsky on Fallout, Interplay and Troika

Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Mon 7 May 2012, 21:18:51

Tags: Arcanum: of Steamworks and Magick Obscura; Blizzard Entertainment; Diablo III; Fallout; Fallout 2; Interplay; Leonard Boyarsky; Retrospective Interview; Troika Games; Vampire: The Masquerade - BloodlinesLeonard Boyarsky is a name that everyone at the RPG Codex knows and loves. The games he worked on, first at Interplay and then at Troika as the company's co-founder and CEO, are among the cRPG industry's most oustanding achievements, and two of them – Fallout 1 and Arcanum – have, along with non-Boyarsky-designed Planescape: Torment, been firmly holding their place in the RPG Codex Holy Trinity™ of computer RPGs for many years already.

Therefore you can imagine how excited we were when Leonard Boyarsky agreed to do a retrospective interview with us, which you can find here. In the interview, Leonard talks Interplay, Troika, and some of the inspirations and design (and business) particulars behind the titles he helped create. Have a snippet -- but be sure to read the full interview as well, it's really interesting!

I repeat, be sure to read the interview in full: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Leonard Boyarsky

We are grateful to Leonard Boyarsky for taking time out of his demanding schedule to do this interview for us, and Che'von Slaughter of Blizzard Entertainment for kindly allowing it to take place. We also thank everyone who suggested their questions for this interview; unfortunately, it was impossible for Leonard to answer all your questions, but I hope you're satisfied with the result!

Therefore you can imagine how excited we were when Leonard Boyarsky agreed to do a retrospective interview with us, which you can find here. In the interview, Leonard talks Interplay, Troika, and some of the inspirations and design (and business) particulars behind the titles he helped create. Have a snippet -- but be sure to read the full interview as well, it's really interesting!

What was the atmosphere and company culture like at Interplay when you worked there, and how did it develop into the situation that prompted you to leave the company?

The atmosphere and culture at Interplay were phenomenal. It was a very creative and inspiring place to work – I mean, they let us do basically whatever we wanted with Fallout. We had almost complete creative freedom on that game. After it shipped, however, it felt like the ‘being left alone in a corner to do whatever we wanted’ era had come to an end. They liked what we had done with Fallout too much to let us run wild anymore, I suppose. Don’t get me wrong – the atmosphere at Interplay was still great, but it felt like we had to move on. Another major factor in our leaving was that we felt that Interplay was going to be facing hard times soon, due to certain choices that were being made. We didn’t want to wait around for it to implode, so we left.

Was founding your own video game developer company something you had long wanted to do, or was it a spontaneous decision? How difficult was it for you as Troika's CEO to balance creative and business challenges?

I never wanted to start my own company, I wanted to stay at Interplay forever. But then Fallout ended and our situation at Interplay changed. It was only then that we seriously started considering starting our own thing. As far as being CEO, that just meant that I was the poor soul who had to negotiate contracts, deal with publishers, write our reports, etc. I spent as little time doing that stuff as possible, which is probably one of the main reasons we didn’t succeed as a company. None of us wanted to do the business stuff, we just wanted to make games. Vampire was really where the management/lead stuff began to crowd out the ‘in the trenches’ day to day work on the games for me.

As you put it in a past interview, "being original is risky." Do you believe originality, and the fact it did not sell, was the chief reason Troika was not able to survive?

Pinning our demise on ‘being too original’ is a bit self-serving for my tastes. For one thing, we were never able to spread our appeal beyond the hardcore RPG market and our sales suffered for it. Not to mention our reputation for releasing ‘unpolished’ games…

Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as an alternative way of video game publishing? Do you believe it can significantly change the landscape of the industry, and would you consider turning to crowdfunding yourself in the future? (For a Troika reunion maybe?)

I think it’s great. It’s wonderful that old school games are being funded this way. I don’t know that it will have much of an effect on the publishing industry, though, unless one of the games is a huge hit.

And I’m happy working at Blizzard, so I don’t see crowdfunding in my future—especially since I have no desire to run my own company again.

The atmosphere and culture at Interplay were phenomenal. It was a very creative and inspiring place to work – I mean, they let us do basically whatever we wanted with Fallout. We had almost complete creative freedom on that game. After it shipped, however, it felt like the ‘being left alone in a corner to do whatever we wanted’ era had come to an end. They liked what we had done with Fallout too much to let us run wild anymore, I suppose. Don’t get me wrong – the atmosphere at Interplay was still great, but it felt like we had to move on. Another major factor in our leaving was that we felt that Interplay was going to be facing hard times soon, due to certain choices that were being made. We didn’t want to wait around for it to implode, so we left.

Was founding your own video game developer company something you had long wanted to do, or was it a spontaneous decision? How difficult was it for you as Troika's CEO to balance creative and business challenges?

I never wanted to start my own company, I wanted to stay at Interplay forever. But then Fallout ended and our situation at Interplay changed. It was only then that we seriously started considering starting our own thing. As far as being CEO, that just meant that I was the poor soul who had to negotiate contracts, deal with publishers, write our reports, etc. I spent as little time doing that stuff as possible, which is probably one of the main reasons we didn’t succeed as a company. None of us wanted to do the business stuff, we just wanted to make games. Vampire was really where the management/lead stuff began to crowd out the ‘in the trenches’ day to day work on the games for me.

As you put it in a past interview, "being original is risky." Do you believe originality, and the fact it did not sell, was the chief reason Troika was not able to survive?

Pinning our demise on ‘being too original’ is a bit self-serving for my tastes. For one thing, we were never able to spread our appeal beyond the hardcore RPG market and our sales suffered for it. Not to mention our reputation for releasing ‘unpolished’ games…

Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as an alternative way of video game publishing? Do you believe it can significantly change the landscape of the industry, and would you consider turning to crowdfunding yourself in the future? (For a Troika reunion maybe?)

I think it’s great. It’s wonderful that old school games are being funded this way. I don’t know that it will have much of an effect on the publishing industry, though, unless one of the games is a huge hit.

And I’m happy working at Blizzard, so I don’t see crowdfunding in my future—especially since I have no desire to run my own company again.

I repeat, be sure to read the interview in full: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Leonard Boyarsky

We are grateful to Leonard Boyarsky for taking time out of his demanding schedule to do this interview for us, and Che'von Slaughter of Blizzard Entertainment for kindly allowing it to take place. We also thank everyone who suggested their questions for this interview; unfortunately, it was impossible for Leonard to answer all your questions, but I hope you're satisfied with the result!

Leonard Boyarsky is a name that everyone at the RPG Codex knows and loves. The games he worked on, first at Interplay and then at Troika as the company's co-founder and CEO, are among the cRPG industry's most oustanding achievements, and two of them – Fallout 1 and Arcanum – have, along with non-Boyarsky-designed Planescape: Torment, been firmly holding their place in the RPG Codex Holy Trinity™ of computer RPGs for many years already. In 1998, after having worked on Fallout 1 and 2 as art director and designer, together with Tim Cain and Jason D. Anderson Leonard Boyarsky left Interplay and went on to co-found Troika Games (incidentally, "troika" means "carriage pulled by three horses" in Russian), the company that released three cult classic yet underappreciated – and undersold – cRPGs: Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura (2001), The Temple of Elemental Evil (2003), and Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines (2004, released the same day as Valve's Half Life 2, which obviously influenced the fact that it only sold 72,000 units). Unfortunately short-lived, Troika failed to create a bestseller cRPG that would secure its future and had to close its doors in 2005 due to financial problems. About a year later, Leonard Boyarsky joined Blizzard Entertainment and is currently working as Senior World Designer on Blizzard's upcoming Diablo III, a new game belonging to the series that needs no introduction. (As you may remember, despite being an ARPG, Diablo II even made it into our 5 RPGs of the decade that we think you should play.)

It is both hard and easy to explain the appeal Troika's games hold for our website's regulars. Hard, because the company's games were by no means perfect, even if all of them did at least one thing perfectly, or almost so: combat in ToEE, world design and non-linearity in Arcanum, writing and atmosphere in Bloodlines. Created on the lofty goals of "Design, Art, Code," the company sought to do ambitious things in all three departments, but despite the many moments of unrivaled greatness and originality, the stated goals and ambitions proved to be more than the company of Troika's size and finances could chew – or the industry could allow it to. Most importantly, however, and this makes it easy to explain our love for it, Troika Games has been one of the very few post-2000 developers who have tried – tried to do RPG design differently and in a non-standardized manner – and, unfortunately, failed. Is there really a rule that developers who try, and choose to go their own original way, also tend to fail an awful lot? As things stand, even with the 'crowd-funding' craze in full swing, it looks like sticking to making sequels is an RPG developer's best chance of survival and making profit. Maybe. We'll have to see how that works out for Obsidian Entertainment, for example.

Anyway, Arcanum, for one, has always held a special power over the admirers of the 1990s-style cRPGs that reached their peak with Fallout. Set in a unique steampunk world where magic and technology are clashing, Arcanum is a role-playing game with a complex character system that allows you to at least reasonably play the role you choose in some way. "Choices and consequences" has traditionally been our catch-cry here at the Codex, and with Arcanum Troika managed to deliver some of the best. Akin to, say, Morrowind, there are many things for the player to do and a big world to explore, but unlike Morrowind you actually will have choices to make and those choices will affect the things you will be able to do so that the game does its best to move in a non-linear fashion. There are also some really – really – well-designed quests and an interesting host of characters to meet. While Arcanum also had its bad sides (the combat), overall it was and remains a classic role-playing game. (The game is available on GOG.com for a measly $5.99, by the way, so you should play it if you still have not. I am looking at you, Mr. Chris Avellone.) Troika's second game, The Temple of Elemental Evil (also available on GOG), while failing to live up to the lofty RPG ambitions of Arcanum, did, however, produce some of the best turn-based D&D combat ever seen in a computer game. Finally, Bloodlines saw Troika drop the classic isometric view and put their RPG skills to task in Valve's first-person Source engine, which resulted in an extremely interesting mix of FPS and RPG, one of the best to this day alongside such games as Deus Ex, with some excellent design and an incredibly addictive writing and atmosphere.

Therefore you can imagine how excited we were when Leonard Boyarsky agreed to do a retrospective interview with us, which you can find below. In the interview, Leonard talks Interplay, Troika, and some of the inspirations and design (and business) particulars behind the titles he helped create.

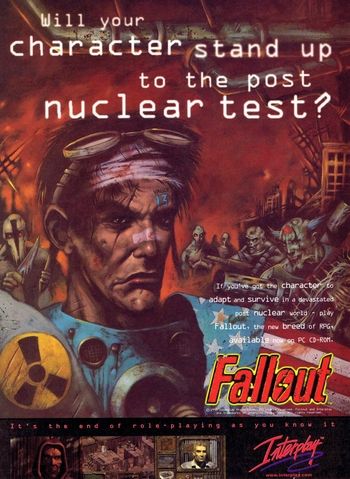

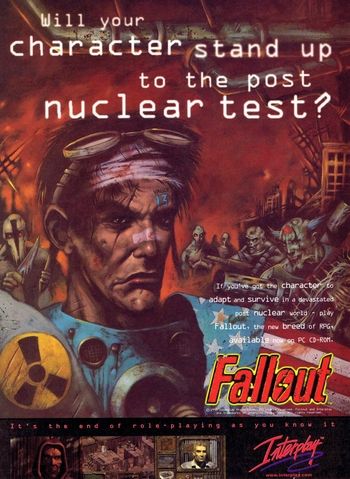

Fallout 1's promotional poster: "It's the end of role-playing as you know it"

How did you find your way into role-playing video game design? Did you come from pen & paper RPGs?

What was the atmosphere and company culture like at Interplay when you worked there, and how did it develop into the situation that prompted you to leave the company?

You are famously associated with the original Fallout mood and look. Was it hard to convince everyone else at Interplay that the "future 1950s" art style was the way to go? What rival ideas were there for the game's look?

Created on the lofty goals of "Design, Art, Code," Troika Games sought to do ambitious things in all three departments.

Aside from Fallout's overall art style, can you give us a rundown of what exactly you designed and wrote for Fallout 1 and Fallout 2? Apart from the look, which is the obvious high point, what contributions to the Fallout games are you most proud of?

Was founding your own video game developer company something you had long wanted to do, or was it a spontaneous decision? How difficult was it for you as Troika's CEO to balance creative and business challenges?

As you put it in a past interview, "being original is risky." Do you believe originality, and the fact it did not sell, was the chief reason Troika was not able to survive?

In the book Gamers At Work, Tim Cain mentions that Troika might have kept itself afloat by taking on various non-RPG projects, but that he was unwilling to sign on to games he "had no interest in playing." How do you feel about this kind of decision today? Is there – was there ever – a place for this kind of idealism in the industry, or should pragmatism have ruled the day?

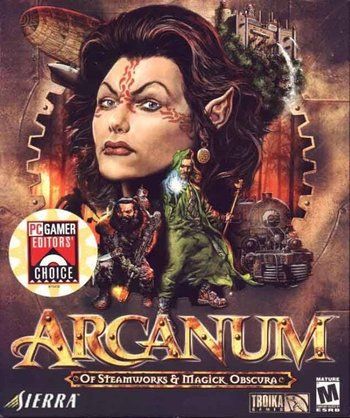

Arcanum's art style was a unique blend of 19th century aesthetics and traditional medieval fantasy – and the game itself was appropriately ambitious.

What were your inspirations for the unique art style and look of Arcanum that blends 19th century aesthetics with traditional medieval fantasy? Also, as far as the game's setting is concerned, what inspired the accent on the conflict between magic and technology?

Vampire the Masquerade: Bloodlines was very different from Troika's other cRPGs. What motivated the shift to action gameplay and first person perspective? Did publisher and market demands have anything to do with it?

As the project lead, what exactly did you design and write for Bloodlines? What is your favorite location in the game, be it among the ones you designed or the ones you did not?

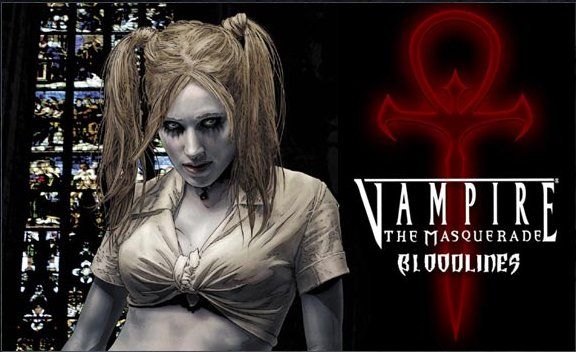

Despite the vampire theme and the great mix of RPG and FPS, Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines failed to sell enough to secure Troika's future.

Bloodlines boasts some of the best voice acting in the video game history as well as an excellent soundtrack. How did the game's sound design come together?

How far in development was Troika's post-apocalyptic cRPG? Can you share some of the ideas you had for the story and setting, as well as for the game's name? Did it represent the direction you wanted the Fallout license to take if Troika had gotten it?

You famously attempted to pitch your post-apocalyptic cRPG to publishers. Can you describe those pitch meetings? How did they go, and what did the publishers have to say in response to your pitch document? Why do you think none of them picked the game up?

Troika's post-apocalyptic RPG unfortunately did not make it beyond a tech demo. All attempts to pitch it to publishers were unsuccessful.

Apart from the post-apocalyptic cRPG, were there any other Troika games in development that failed to see the light of day? If there were, what can you tell us about them?

How did your decision to join Blizzard to work on Diablo III come about?

In your view, what makes a good role-playing game and what are the defining elements of the genre?

Currently, Leonard Boyarsky is working as Senior World Designer on Blizzard Entertainment's upcoming action-RPG Diablo III.

What do you think about the current state of the cRPG industry and how do you envisage the future of the genre? Are there certain trends that are worrisome to you or, on the contrary, that you especially appreciate?

For turn-based cRPGs, do you prefer Temple of Elemental Evil's full party control or Fallout’s single controllable character with followers?

Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as an alternative way of video game publishing? Do you believe it can significantly change the landscape of the industry, and would you consider turning to crowdfunding yourself in the future? (For a Troika reunion maybe?)

We are grateful to Leonard Boyarsky for taking time out of his demanding schedule to do this interview for us, and Che'von Slaughter of Blizzard Entertainment for kindly allowing it to take place.

It is both hard and easy to explain the appeal Troika's games hold for our website's regulars. Hard, because the company's games were by no means perfect, even if all of them did at least one thing perfectly, or almost so: combat in ToEE, world design and non-linearity in Arcanum, writing and atmosphere in Bloodlines. Created on the lofty goals of "Design, Art, Code," the company sought to do ambitious things in all three departments, but despite the many moments of unrivaled greatness and originality, the stated goals and ambitions proved to be more than the company of Troika's size and finances could chew – or the industry could allow it to. Most importantly, however, and this makes it easy to explain our love for it, Troika Games has been one of the very few post-2000 developers who have tried – tried to do RPG design differently and in a non-standardized manner – and, unfortunately, failed. Is there really a rule that developers who try, and choose to go their own original way, also tend to fail an awful lot? As things stand, even with the 'crowd-funding' craze in full swing, it looks like sticking to making sequels is an RPG developer's best chance of survival and making profit. Maybe. We'll have to see how that works out for Obsidian Entertainment, for example.

Anyway, Arcanum, for one, has always held a special power over the admirers of the 1990s-style cRPGs that reached their peak with Fallout. Set in a unique steampunk world where magic and technology are clashing, Arcanum is a role-playing game with a complex character system that allows you to at least reasonably play the role you choose in some way. "Choices and consequences" has traditionally been our catch-cry here at the Codex, and with Arcanum Troika managed to deliver some of the best. Akin to, say, Morrowind, there are many things for the player to do and a big world to explore, but unlike Morrowind you actually will have choices to make and those choices will affect the things you will be able to do so that the game does its best to move in a non-linear fashion. There are also some really – really – well-designed quests and an interesting host of characters to meet. While Arcanum also had its bad sides (the combat), overall it was and remains a classic role-playing game. (The game is available on GOG.com for a measly $5.99, by the way, so you should play it if you still have not. I am looking at you, Mr. Chris Avellone.) Troika's second game, The Temple of Elemental Evil (also available on GOG), while failing to live up to the lofty RPG ambitions of Arcanum, did, however, produce some of the best turn-based D&D combat ever seen in a computer game. Finally, Bloodlines saw Troika drop the classic isometric view and put their RPG skills to task in Valve's first-person Source engine, which resulted in an extremely interesting mix of FPS and RPG, one of the best to this day alongside such games as Deus Ex, with some excellent design and an incredibly addictive writing and atmosphere.

Therefore you can imagine how excited we were when Leonard Boyarsky agreed to do a retrospective interview with us, which you can find below. In the interview, Leonard talks Interplay, Troika, and some of the inspirations and design (and business) particulars behind the titles he helped create.

Fallout 1's promotional poster: "It's the end of role-playing as you know it"

How did you find your way into role-playing video game design? Did you come from pen & paper RPGs?

I did not have a lot of experience with pen and paper RPGs, unfortunately. I was fascinated with DnD and other RPGs when I was younger, but I never found a good group of people to play with. My first PnP experiences were at Interplay with Tim Cain running a Conan campaign. He also ran a pretty cool GURPS Space campaign, if I recall correctly.

The fact that I ended up a game designer was purely by accident. I always liked writing, but I was an artist at heart – it’s what I got my degrees in in college. My first foray into design was at the beginning of Fallout. A group of us got together and decided what we wanted the game to be from a design and story standpoint. I was fortunate enough to have the others listen to someone like me—who had absolutely no experience in design—blather on about what I wanted from the game. It was definitely a shared vision between all of us. Once we had decided on the necessary basics of the game (multiple ways to solve each quest, branching dialog, consequences for player choices, basic area design, etc.) I went back to being the art director and didn’t think anything else about it. However, once we finished the art for the game and had the time to start playing it in earnest, we found that a lot of our original area design and philosophy somehow hadn’t made it into the game. I remember specifically that there was nothing in the Brotherhood of Steel apart from the NPCs with talking heads – and we were supposed to be shipping soon. So Jason and I, with the unbounded arrogance of youth, decided we were going to start writing and editing dialogues and adding quests for the game. And so I became a game designer.

The fact that I ended up a game designer was purely by accident. I always liked writing, but I was an artist at heart – it’s what I got my degrees in in college. My first foray into design was at the beginning of Fallout. A group of us got together and decided what we wanted the game to be from a design and story standpoint. I was fortunate enough to have the others listen to someone like me—who had absolutely no experience in design—blather on about what I wanted from the game. It was definitely a shared vision between all of us. Once we had decided on the necessary basics of the game (multiple ways to solve each quest, branching dialog, consequences for player choices, basic area design, etc.) I went back to being the art director and didn’t think anything else about it. However, once we finished the art for the game and had the time to start playing it in earnest, we found that a lot of our original area design and philosophy somehow hadn’t made it into the game. I remember specifically that there was nothing in the Brotherhood of Steel apart from the NPCs with talking heads – and we were supposed to be shipping soon. So Jason and I, with the unbounded arrogance of youth, decided we were going to start writing and editing dialogues and adding quests for the game. And so I became a game designer.

What was the atmosphere and company culture like at Interplay when you worked there, and how did it develop into the situation that prompted you to leave the company?

The atmosphere and culture at Interplay were phenomenal. It was a very creative and inspiring place to work – I mean, they let us do basically whatever we wanted with Fallout. We had almost complete creative freedom on that game. After it shipped, however, it felt like the ‘being left alone in a corner to do whatever we wanted’ era had come to an end. They liked what we had done with Fallout too much to let us run wild anymore, I suppose. Don’t get me wrong – the atmosphere at Interplay was still great, but it felt like we had to move on. Another major factor in our leaving was that we felt that Interplay was going to be facing hard times soon, due to certain choices that were being made. We didn’t want to wait around for it to implode, so we left.

You are famously associated with the original Fallout mood and look. Was it hard to convince everyone else at Interplay that the "future 1950s" art style was the way to go? What rival ideas were there for the game's look?

When I told people about my ideas for the look of the game, they looked at me like I was crazy. Why would we make a post-apocalyptic game look like a cheesy fifties B-movie? Much to Interplay’s credit however, even though they thought I was insane, no one said we couldn’t do it. So we did. I started pitching the fifties vibe so early that there were really never any other competing art styles considered.

Created on the lofty goals of "Design, Art, Code," Troika Games sought to do ambitious things in all three departments.

Aside from Fallout's overall art style, can you give us a rundown of what exactly you designed and wrote for Fallout 1 and Fallout 2? Apart from the look, which is the obvious high point, what contributions to the Fallout games are you most proud of?

I’m not going to try to write an exhaustive list of what I designed/wrote in Fallout, as that would be, well, exhausting. When I think about all the writing we did on Fallout, the first things that always come to mind were the edits we had to do for the talking head conversations. A lot of times the conversations didn’t make sense or deliver the information they were supposed to, but they had already been recorded and we didn’t have the budget to rerecord them – so we had to go in and edit/rewrite the player responses and rearrange the NPC lines so that the conversations worked. In some instances, like Vree, the information we wanted to impart to the player just wasn’t there so I had to add her assistant (Sophia, I think?) so that there was at least an NPC around who did have the necessary info. And she wasn’t the only one—we had to add several NPCs with vital information that was supposed to be covered with the talking heads but for some reason wasn’t. I did extensive rewrites on Gizmo, Killian and the Master as well as one or two others. One scenario I really enjoyed designing was in Adytum – Zimmerman’s situation with the regulators, his son and the Blades. I wrote a lot of NPCs, too many to list (or remember). I also wrote some of the holodisks.

From a design standpoint, I’m really proud of the tone we hit for the game, the humor style. Even though I was the one who started the fifties ironic horror/comedy vibe, I can’t take full credit for its final form in the game – it really ended up being an extension of a combination of our personalities. Once it was established, however, I was the policeman who made sure that we hit that tone whether it was in the art or the design. Above everything else, though, the two things I am specifically most proud of are the intro and ending to the game. I guess those would be half design and half art, but I’m proud of both aspects of them. I think the intro did a great job setting the mood, and the ending had a nice haunting feel to it. I still can’t believe Tim let us kick the vault dweller out of the vault to end the game.

For Fallout 2, Jason, Tim and I designed the main story arc and a few side quests before leaving Interplay. They kept a lot of what we had designed, but changed some significant parts of it as well.

From a design standpoint, I’m really proud of the tone we hit for the game, the humor style. Even though I was the one who started the fifties ironic horror/comedy vibe, I can’t take full credit for its final form in the game – it really ended up being an extension of a combination of our personalities. Once it was established, however, I was the policeman who made sure that we hit that tone whether it was in the art or the design. Above everything else, though, the two things I am specifically most proud of are the intro and ending to the game. I guess those would be half design and half art, but I’m proud of both aspects of them. I think the intro did a great job setting the mood, and the ending had a nice haunting feel to it. I still can’t believe Tim let us kick the vault dweller out of the vault to end the game.

For Fallout 2, Jason, Tim and I designed the main story arc and a few side quests before leaving Interplay. They kept a lot of what we had designed, but changed some significant parts of it as well.

Was founding your own video game developer company something you had long wanted to do, or was it a spontaneous decision? How difficult was it for you as Troika's CEO to balance creative and business challenges?

I never wanted to start my own company, I wanted to stay at Interplay forever. But then Fallout ended and our situation at Interplay changed. It was only then that we seriously started considering starting our own thing. As far as being CEO, that just meant that I was the poor soul who had to negotiate contracts, deal with publishers, write our reports, etc. I spent as little time doing that stuff as possible, which is probably one of the main reasons we didn’t succeed as a company. None of us wanted to do the business stuff, we just wanted to make games. Vampire was really where the management/lead stuff began to crowd out the ‘in the trenches’ day to day work on the games for me.

As you put it in a past interview, "being original is risky." Do you believe originality, and the fact it did not sell, was the chief reason Troika was not able to survive?

Pinning our demise on ‘being too original’ is a bit self-serving for my tastes. For one thing, we were never able to spread our appeal beyond the hardcore RPG market and our sales suffered for it. Not to mention our reputation for releasing ‘unpolished’ games…

In the book Gamers At Work, Tim Cain mentions that Troika might have kept itself afloat by taking on various non-RPG projects, but that he was unwilling to sign on to games he "had no interest in playing." How do you feel about this kind of decision today? Is there – was there ever – a place for this kind of idealism in the industry, or should pragmatism have ruled the day?

I don’t think it was idealism. If we had no interest in playing a certain style of game, we would have no passion for making it. Making games is not easy – you definitely need to have passion for what you’re doing to be successful. Without the passion, you’re sunk.

Arcanum's art style was a unique blend of 19th century aesthetics and traditional medieval fantasy – and the game itself was appropriately ambitious.

What were your inspirations for the unique art style and look of Arcanum that blends 19th century aesthetics with traditional medieval fantasy? Also, as far as the game's setting is concerned, what inspired the accent on the conflict between magic and technology?

The visual look of Arcanum really flowed from our initial idea that we wanted to bring an industrial revolution to a fantasy world. I really love the steampunk aesthetic, with valves and gears and exposed machinery. I can’t really remember any one specific touchstone or inspiration for the look, we just did a lot of research on the industrial revolution and the 19th century. The decision to focus on the conflict between magic and technology was part of our initial inspiration to bring technology into a magical world—it just seems natural that they would be in conflict with each other. As far as the system end of the magic/tech conflict, that would be all Jason and Tim. I stay away from system stuff for the most part.

Vampire the Masquerade: Bloodlines was very different from Troika's other cRPGs. What motivated the shift to action gameplay and first person perspective? Did publisher and market demands have anything to do with it?

We had done two isometric games back to back, so when the opportunity arose to work with Valve’s Source engine it felt like a good time to try something different. It was as simple as that. The inclusion of the Source engine definitely helped sell the game to the publisher.

As the project lead, what exactly did you design and write for Bloodlines? What is your favorite location in the game, be it among the ones you designed or the ones you did not?

As I said before, the management/lead demands really cut into my actual day to day work on Vampire, but I did get in there and get my hands dirty on some stuff. I did a fair amount of character concepts and texture work on the art side, and I reviewed, revised and/or edited much of the dialogues for the game. Chad Moore, Jason and myself came up with the basic storyline for the game, and I also was able to write a few of the side characters.

My favorite location in the game definitely has to be the haunted house – several people took turns trying to make that work, but it wasn’t until Jason took it over that it really began to shine.

My favorite location in the game definitely has to be the haunted house – several people took turns trying to make that work, but it wasn’t until Jason took it over that it really began to shine.

Despite the vampire theme and the great mix of RPG and FPS, Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines failed to sell enough to secure Troika's future.

Bloodlines boasts some of the best voice acting in the video game history as well as an excellent soundtrack. How did the game's sound design come together?

I really have to give credit to one of our designers, Brian Mitsoda, and our casting and voice director Margaret Tang for the VO work. On the sound/music side, Jason was the point man on that along with our composer Rik Schaffer. I think they all did a great job with our limited resources.

How far in development was Troika's post-apocalyptic cRPG? Can you share some of the ideas you had for the story and setting, as well as for the game's name? Did it represent the direction you wanted the Fallout license to take if Troika had gotten it?

We only had an engine demo, and were just starting to talk about some possible directions we could take the game when Troika closed its doors. We just knew we wanted to revisit the post-apocalyptic genre. Believe it or not, we really never talked much about what we would do with Fallout if we ever got the chance to work on it again.

You famously attempted to pitch your post-apocalyptic cRPG to publishers. Can you describe those pitch meetings? How did they go, and what did the publishers have to say in response to your pitch document? Why do you think none of them picked the game up?

We didn’t get very far with any of our pitches. A few introductory phone calls with no interest on the side of the publishers. I’m sure there were many reasons for the lack of interest, not the least of which being that none of our games had really been a hit.

Troika's post-apocalyptic RPG unfortunately did not make it beyond a tech demo. All attempts to pitch it to publishers were unsuccessful.

Apart from the post-apocalyptic cRPG, were there any other Troika games in development that failed to see the light of day? If there were, what can you tell us about them?

There were a few pitch documents we were working on, but nothing that we really had rallied behind as a company. One thing we did do was a demo using the Source engine for a World of Darkness werewolf game, but I don’t think we ended up even getting the chance to show that one to anybody. At that stage in the life of Troika I was just trying to get publishers interested in talking to us about the possibility of doing a game, any game, but I was unsuccessful.

How did your decision to join Blizzard to work on Diablo III come about?

It was an easy decision, really. I had sent my resume to Blizzard and they called me in to talk about working on Diablo. I thought it was a great opportunity so I jumped at the chance.

In your view, what makes a good role-playing game and what are the defining elements of the genre?

I don’t think there is one set of criteria for what makes a good role playing game—it depends on what type of RPG you’re making. There would be a whole different list of criteria for a Mass Effect style game than there would be for Diablo III, for instance. It just depends on what the goals of the game are. However, one thing all RPGs do need to have is the ability to choose how to play your character in terms of skills and abilities.

Currently, Leonard Boyarsky is working as Senior World Designer on Blizzard Entertainment's upcoming action-RPG Diablo III.

What do you think about the current state of the cRPG industry and how do you envisage the future of the genre? Are there certain trends that are worrisome to you or, on the contrary, that you especially appreciate?

I think it’s a very interesting time for RPGs, with the success of games like Mass Effect and Fallout 3 and the reappearance of old school titles like Grimrock and Wasteland 2. I hope we continue to see games from both ends (and even the middle) of the RPG spectrum. More stuff to play!

For turn-based cRPGs, do you prefer Temple of Elemental Evil's full party control or Fallout’s single controllable character with followers?

As I said before, I’m not a systems guy by any means, so this is just more of a personal than professional opinion, but I like controlling one character more than a party. I like to feel that I’m the hero of the game, and having a party dilutes that somewhat for me. Of course, there is something to be said for the more strategic nature of party based games…

Given the recent Kickstarter success stories of Tim Schafer and Brian Fargo, what do you think of crowdfunding as an alternative way of video game publishing? Do you believe it can significantly change the landscape of the industry, and would you consider turning to crowdfunding yourself in the future? (For a Troika reunion maybe?)

I think it’s great. It’s wonderful that old school games are being funded this way. I don’t know that it will have much of an effect on the publishing industry, though, unless one of the games is a huge hit.

And I’m happy working at Blizzard, so I don’t see crowdfunding in my future—especially since I have no desire to run my own company again.

And I’m happy working at Blizzard, so I don’t see crowdfunding in my future—especially since I have no desire to run my own company again.

We are grateful to Leonard Boyarsky for taking time out of his demanding schedule to do this interview for us, and Che'von Slaughter of Blizzard Entertainment for kindly allowing it to take place.