BattleTech shows why adapting board games takes more than copying the rules

There have been more than 20 BattleTech videogames since the board game was released back in 1984. Each time the game has been adapted to the screen its core elements have been chopped and changed - it’s a process the game’s creator, Jordan Weisman, embraces. “When a game goes from one genre of game to another, there's an adaptation that needs to be done,” he tells us. “We see that in movies and television all the time.”

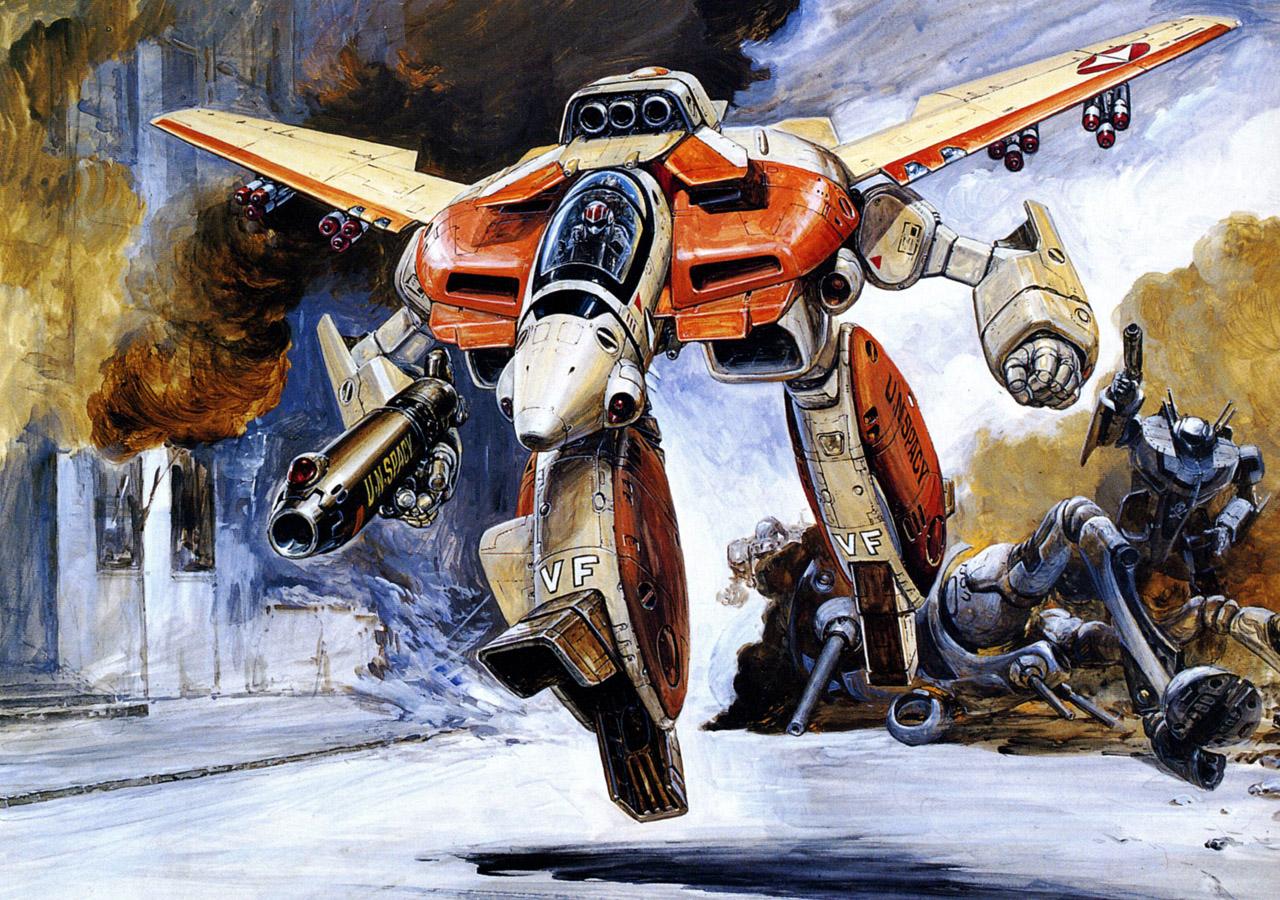

In the tabletop version of BattleTech, you command a lance of mechs in battle against another commander. You both select your mechs based on their weight class and then kit them out with armour and weapons that dictate their abilities and modifier rolls. How you perform on the battlefield depends on your tactics and your dice rolls. It’s a tense, tactical game in which you need to manage your mechs’ heat and outflank your opponent to cause real damage. You are, after all, commanding multi-story, walking tanks.

However, when it came to MechWarrior games - a series of games that adapted BattleTech into a first-person shooter - there had to be some fundamental changes. While the mech design and heat systems remained, all the dice rolls were thrown out.

“The difference between a twitch-based game and a tactical game is pretty big,” Weisman says. The reward for players is skill-based, not tactical. “You're trying to hit something that's physically moving as you're physically moving. It becomes a real skill you have to develop,” he adds. With that in mind, MechWarrior recognised the change in perspective, from looking down on the table to being in the cockpit, and rewarded players for focusing their fire on individual limbs. “In the twitch-based game, being able to target specific areas of the body becomes a rewarding skill you build as a player,” Weisman explains.

In the BattleTech board game, you can only single out limbs or the cockpit of an enemy mech after it’s been knocked to the floor, because, as Weisman points out, “there is no skill that has to be developed on the part of the player to successfully shoot at legs.”

Weisman goes further, explaining that if you put limb shots into the tactical take on the game “we end up with one of two things. Either: a) the odds to hit were so low that you missed a bunch of times and it became frustrating, or b) the percentage chance to hit let you hit a number of times, in which case mechs were destroyable much too quickly.

“You're just clicking on a headshot and rolling for your lucky headshot number. Or you'll take their legs out really quickly,” Weisman summarises.

Currently, Weisman’s studio, Harebrained Schemes, is working on a turn-based tactical videogame version of BattleTech called… er, BattleTech. Despite it being much closer to the board game than, say, MechWarrior, it is still an adaptation.

“Tabletop play is very different from computer game play,” Weisman tells us. “You have the inherent socialness of people at the table, you have the tactile nature of the table and the pieces, and the tableau of the game.

If you simply take the rules of BattleTech and make them work in a videogame those aspects of the board game don’t carry over, Weisman explains. However, the biggest loss is a small thing in principle but a major one in practice: rolling a dice.

“There is an inherent drama to a die roll that doesn't exist in a computer game,” Weisman says. “You can put little dice rolling across the screen but it's not the same because tabletop gamers know for sure that they can psychically control dice. They've known this forever. And we don't believe we can psychically control digital dice.

“I think it's true of any game that uses a dice roll and a table. That's not reproduced by a percentage number on the screen.”

We saw this first-hand with Full Control’s recreation of Space Hulk,

when Tim and I played we found the game had no tension and the outcome of moves were frustrating.

Knowing these issues himself, Weisman and his team didn’t aim to reproduce the ruleset: “We set our goal as to reproduce the same tactical considerations and the same unit identification. If you're talking about a particular mech, that mech should feel the same in our game as it did on the tabletop. We wanted to recreate the tactical considerations, the strategic considerations, the lore, and the feeling of it, but not be concerned with reproducing the exact mechanics.”

It’s not only that a vital part of the game would be lost, though. As well thought of as BattleTech is, Weisman is quick to point out that the “design is 35 years old. So it's not even a modern tabletop game, it's one from another era. In all entertainment things change, things evolve. A 35-year-old design is pretty archaic.”

As Weisman puts it, in BattleTech “everything was a modifier. It was all one grey long continuum of modifications to the risk/reward relationship. More modern games try to present players with more discrete, actionable choices, that have more clear risk/reward relationships.” While the team don’t want to lose what made BattleTech the game it’s recognised as, they did want to infuse the old game with some modern thinking.

The relationships between the game’s systems was always what made skirmishes in BattleTech compelling, you were always weighing up the payoff of your plans. You could charge your mech up the battlefield, firing all its weapons into the chest of an enemy machine, disarticulating its limbs, but doing so would likely overheat your mech, leaving you unable to act in the next turn - exposing your mech to a counter-attack. But a more cautious approach that leaves your mech active might see you attacked by the mech that the aggressive approach could have finished off.

“How weapons, armour, and heat sinks, all those things interact and the balance they have in the tabletop game, that was very important for us to maintain as closely as possible,” Weisman says.

In bringing the game to PC, Weisman’s team has deepened the relationship between the systems of heat, stability, and armour. “When you get yourself too hot you're actually physically wounding the mech, not just providing modifiers, like it did in the tabletop, but actually wounding the mech itself,” he says. The most recent update added flamethrowers to the game, so now you can overheat any mechs to shut them down and cause massive internal damage. The stability system means that as mechs take hits they become unstable and, if they become too unstable, fall over. A downed mech is particularly vulnerable, and one of the few times you can call a shot on a specific mech body part. The system encourages risky moves, like getting a mech up close and personal for a melee attack, which can knock a mech down better than any gun shot.

“You get a nice triangle relationship between damage, stability, and heat,” Weisman says.

Each time BattleTech is adapted it moves away from the original design, but it also brings the core tenets of the series into sharper focus. No BattleTech game would be complete without heat management, nor the interplay between the different mech weight classes and, despite being in different genres, BattleTech and MechWarrior all give you similar breakdowns of the differences between a Mad Cat, an Atlas, and a Firefly.

It’s a fascinating process to see; like the mechs at the heart of the BattleTech, every aspect of the series can be stripped out, altered, and replaced, but the chassis remains intact and recognisable.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)