grimace

Arcane

- Joined

- Jan 17, 2015

- Messages

- 2,112

Next update we'll also be asking backers for some fake advertising plugs to put in the game. So get your creative hats on.

Here's an idea:

Excidium II Cat Food

Not just for cats. Not just food.

Next update we'll also be asking backers for some fake advertising plugs to put in the game. So get your creative hats on.

Don't we all.I want to play this game

He visited the Codex.what happened to the guy?

Ate cat food.what happened to the guy?

Sure, but it's very inconsiderate of catfood all the same.Ate cat food.what happened to the guy?

Ate cat food.what happened to the guy?

on the 4 white screens? Obvious Easter Egg for the true connoisseur

on the 4 white screens? Obvious Easter Egg for the true connoisseur

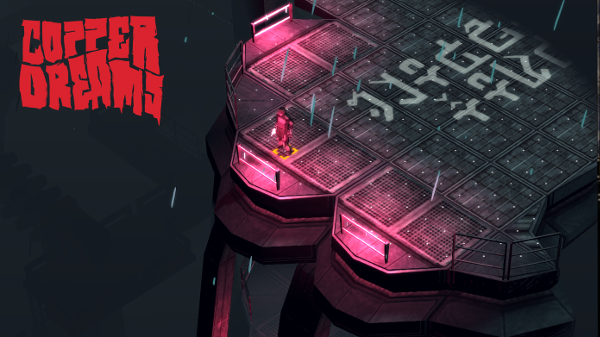

Interview: Copper Dreams’ Hannah Williams

on September 25, 2017

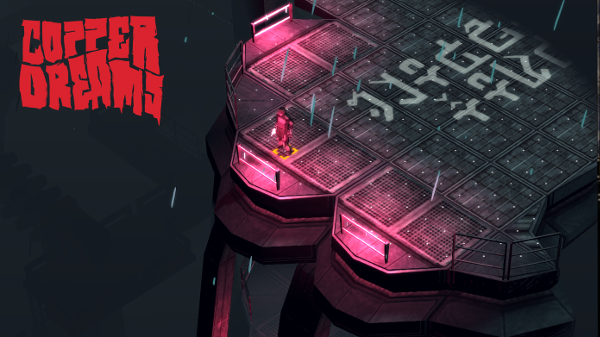

Copper Dreams transports players to a cyberpunk world of corporate war and horror far from Earth. The party-based isometric CRPG from Whalenought Studios employs unique, nuanced mechanics, and I chatted with dev Hannah Williams on the novelties of the project.

Erik Meyer: The release of games like Fallout, Diablo, and Ultima Online in the ’90s established isometric RPGs as a genre, but recent projects like No Truce With The Furies seek to expand standard conventions, such as dialogue. Your project uses a health system comprised of wounds in the place of a more abstract HP meter. Similarly, you have extensive sneak and weapons options systems. What other novel features and content do you see yourselves adding to Copper Dreams? What do you see yourselves implementing that you haven’t seen done elsewhere?

Hannah Williams: The heart and soul of Copper Dreams has always been creating a cozy, p&p roleplaying experience. A comfortable playground that allows you to approach the world as you would in a tabletop game, a ruleset that won’t hamstring your adventure by limiting your tools to those fed through specific dialogue options or one-note item uses. When an RPG does just that, rationing out your actions or even suddenly gifting you a narrative tool that allows you to do something that isn’t possible in game mechanics, it takes away the joy of actually roleplaying without being told what to do. Partially because the game designer spoon-fed you your actions like they did the narrative, but also because it also creates a sense of disorientation. Dice are rolled and actions are performed on the result, that’s a great start, but beyond that there’s a lot we wanted to rethink what a player has control of and what to do with it.

Here’s an example: I’m talking to a guard and I pick option A to palm him five gold coins so he’ll let me pass unmolested. Neat! Glad I didn’t have to stab him, he looked like he had a nice family at home waiting for him. But wait, can I do that with anyone? I never got that bribe option in dialogue before. Why did it pop up with him and not the now-dead guard downstairs? Was one less important on my narrative path? This one has a red vest, does that mean something? Did a writer get distracted and forget to add the dialogue option in before? Was there a secret charisma roll that I finally passed? Am I overthinking this? I’m scared, help! I wish I just had a button that let’s me try to bribe someone whenever I want to!

Most players, of course, are used to a bribe option popping up in dialogue and don’t need to dig out their smelling salts when it happens, but you get the idea. If you give a player all their tools to be used at will, it makes them feel like they can do anything they want, and also gives a sense of security, despite running around in an hostile environment, because you always know what your options are. If you want to try to bribe the final boss, by all means, give it a shot. If you want to bribe a chicken, do that too. Making the DM miserable is mostly what p&p is about, and the least we could do is give the player the freedom to do that to us.

The challenge of this is creating all these tools for players to use at will. Manually jumping over obstacles instead of clicking their hit box to disable them, climbing a roof for height advantage, dropping to a crouch to avoid a missile, dragging cigarettes out of your backpack to an NPC so they will spill their secrets, using your crossbow like a hammer when you’re out of bolts or just throwing it against the wall to make noise. These are the kind of things that we think create that cozy tabletop experience, and what will make our ruleset feel different.

EM: You ran a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Copper Dreams, but this isn’t your first Kickstarter, as you already had Serpent in the Staglands under your belts. What kinds of things did you learn from your previous projects and crowdfunding efforts that informed your process this go-around, and what have the community responses been like?

HW: Our Kickstarter community has always been a true delight in the experience of creating games. We are pretty introverted people, and when we started the company the idea of building a community was quite frankly terrifying. Most 13 year olds have more Twitter followers than we do. But then we took Serpent in the Staglands to Kickstarter, and suddenly there were people talking to us! And giving us ideas and suggestions! It was wonderful. Not just because no one should develop a game in a bubble, but just being digitally surrounded by people who love CRPGs was great. Even when they’re disappointed in you, it’s really great having people along for the ride to explore the possibilities of the best genre of computer games.

We had a lot of repeat backers from Serpent to Copper Dreams, and it’s been exciting to continue to see their comments and hear from them. As a two-person team, we think people know they are getting a very authored experience, a personalized product that comes from just two people creating all the art, writing, and gameplay. All that takes time though, and we learned from Serpent that we needed to allocate more time to ensure that all the ruleset and gameplay connections are working properly. So we’d like to get more feedback from our Kickstarter backers when we’re ready, but thus far they’ve been very supportive and most of all, very patient.

EM: I’m interested in the game’s freedom of movement, including vertical structures, which have often been tricky for isometric projects. What led to your decision to unite the buildings and locations of a particular district as one navigable space (as opposed to separately loaded areas), and what kinds of challenges have you faced in making movement through different areas feel intuitive?

HW: Vertical movement was our our particular obsession for a lot of this, besides tuning the tick/tile system. It’s high risk, because we were new to 3D and there are a ton of level design and programming challenges involved, but also high reward, because who doesn’t want to run around rooftops and climb walls and evade enemies by careening off of tall buildings?

It also felt necessary for that tabletop experience we’re gunning for. If you’re playing a p&p game and spot-check a tripwire, you’d just step over it, or roll to. Most isometric games fall prey to the nature of point n’ clicking, not easily allowing that, so you’d have to instead roll to disarm it or navigate around it. For non-grid based games that convey a level of ‘freedom’, that seems like phoning it in. Or if you want height advantage and you see a crate or short roof, you should just climb it. With the tile-based system we were able to allow this freedom without the need for any hand-eye coordination or reflexes. Moving in and out of buildings with a rotatable camera is important too. It adds a layer of excitement to seamlessly sneaking and getting into combat throughout the city that map loading wouldn’t allow for. Jumping outside a building window onto a lower roof to try to lose some guards chasing you is fun and gives you a lot of freedom. If you were playing a tabletop game, a DM wouldn’t say the guards lose you because you’re now in a new map.

The verticality we had envisioned has certainly been tough to implement, stirring emotions ranging from sheer panic to total excitement as we’ve evolved our systems for creating levels and seamless experiences when roofs or whole buildings that are blocking you need to disappear, or you run up staircases to a new floor and new content needs to be ready for you. If a roof disappears, is there a fog of war? Is it just a slice downward, or a big hole? They are questions asking how much do we want the player to see how the sausage was made, right? If we just chop roofs off or something, players can see how arbitrarily maps are designed. How can we make that vertical transition within a building not abrupt? How much needs to disappear so you can shoot someone at the end of a hallway? Have other isometric games done this (a few), and did they do it well (eh)? These are questions we’ve grappled with, and they’ve definitely been a challenge, but we’re actually very happy with how everything was solved.

EM: The game includes a multitude of factions, from The Mayflower Initiative to Agro-Fax and The Faith, each with different strengths and goals, to speak to the unique lore you’ve created as part of the development process. As a cyberpunk off-world dystopian setting, what elements have become the core of the experience you’re providing, and what kinds of things have you had to leave out?

HW: To get a feel for the experience, we like to picture a stranded Vietnam soldier behind enemy lines, slapping bandages on his wounds, constantly fighting ammo scarcity, confused, and just hoping he makes it through the night. Then take that solider, set him under some neon glowing lights and screw a few tinfoil hats on him and you have Copper Dreams.

The city itself is stamped with the distrust and suspicion bred by the warring syndicates. While the city is populated, the citizens are not on your side, because no one is on their side, and will rat you out if you’re acting fishy. They are frightened of the syndicates and broken down by the day to day difficulties of survival amongst scarce resources and constant faction fighting. You’ve got your bounty and a gun, and you’re the only person you can trust in the game. In the way of gameplay, that means solving mysteries yourself without a guide, patching yourself up, and bribing and making relationships with those you think you can trust. The premise of how people on the colony feed (and heal) themselves is also explored in the campaign setting, and while it’s fun and easy to side-eye our failing Big Pharma-based medicinal lifestyle today, it’s a very cyberpunk appropriate theme that’s interesting to explore.

Our original concept for the Kickstarter was always pretty narrow, we always envisioned the game as a ‘one-shot’ campaign, which in this case meant something compact that you could try with different play-throughs and different randomized content in a more city-simulation based campaign. The core systems of the playground were already pretty vast as they were, so we haven’t really left anything out, fortunately, but haven’t needed to add much more in than we had planned. Mostly, we just focused on iterating on what we had planned for.

EM: You incorporate a wait period into the turn-based combat system, meaning actions don’t execute immediately and can be interrupted. Can you speak a bit more to the genesis of this mechanic and how it translates to both small group (one-on-one fighting, for example) and large group (a bar brawl) encounters? How do you see players and NPCs anticipating enemy actions via this time element, and what added dimensions come with it, from a tactical point of view?

HW: This turn-time feature is really the crux of the game system and has been in flux since the Kickstarter. There’s been a lot of iterating. We wanted to do a turn-based system that is less abstract than the traditional model, where attacks take time and you can interrupt each other. It started with more of a combat timeline, represented in seconds, where character icons would travel across it while they performed their turn. They could get stopped on it, or when it finished they’d be prompted to do their next turn.

This was fun but had flaws. The time-based element was too arbitrary and became frustrating to try to compare between characters during combat. Eventually, we got rid of the actual representation of time in seconds and just had ‘ticks’ evolving into this now step-by-step turn based model. These ticks represent how long something takes, a certain attack might take 3 to prep, and 2 to recover from, where moving a certain distance might just take 4. If you get hit, you add more ‘hit’ ticks, which you have to wait through to get back to your action. Then there’s a tick to tile relationship as well, where you can see how many tiles you can cover while moving in the next tick, or how many tiles a bullet will pass through during one.

The beauty of the simulationist-based combat and ruleset is that things will play out largely how you’d expect them to. If there’s enough people on the screen, it turns into a bullet hell, but because it’s still turn-based, you have time to consider your tactics and adjust to the number of people you’re fighting and their abilities and strategies. Players (should) and NPCs will be seeking cover as much as they can to start with, as the life of characters can be quite limited. One-on-one combat gives you an easier opportunity to get the jump on an enemy or have a very dedicated shootout with each of you cat-and-mousing in and out of cover if you didn’t kill them stealthily or something. Since enemies can often be dispatched easily, other simulated aspects like the noise weapons make, calling for backup, or running for cover make engagements more interesting. There’s nothing stopping a player from sneaking around or instant killing anyone if they set up a roll nicely. There is no omnipresent AI for enemies, they individually read player location and actions based on your current position, stance and knowledge of what has passed. Different enemies could have different last known positions of where you might be, but alerting one in the presence of another would alert both to your location (or general direction). So gaming their senses is certainly part of the tactics, as you would in a stealth game.

To help show all this, players can anticipate enemy actions through the ticks that show up after an enemy chooses an action, and plan accordingly during their turns. If you see that they’re going to do something in 5 ticks, you can pick an action that takes less time, although potentially reducing your hit chance roll at the price of speed. We have a lot of indicators letting players know when bullets are coming and the direction someone is moving, so when that bullet-hell game happens, you can duck, crawl, and run to avoid what you can to get to more cover.

EM: In terms of in-game 3D assets, I note that the character models are low-poly and stylized by way of careful skinning, and as we view the game from afar, the world has a consistent feel. In terms of art direction and creation, what have been key goals and guiding factors? Do you run into hardware/game engine limitations? What ends up demanding the majority of your time?

HW: Our goal was definitely to custom design everything ourselves to make sure we could create a look of stylized consistency. Glad you think that’s coming through! We’re always tweaking the visuals to get it just right with everything. The game started with pixel art characters (playing with what we knew), but that’s evolved into sketchy palette-knife-like character textures with color blocked, chunkier models. It’s supposed to be abstract and stylized enough for a player to use their imagination to fill in some blanks. We loved that about 2D pixel art and aimed to do the same in 3D, and this just sort of naturally evolved as we took more stabs at it.

With a style like this, hardware was never really an issue. Our direction was never the Icarus of ‘realism,’ so it was just a great bonus that our chosen art style also leaves a small footprint. It does leave room for some of our more intensive systems, like the volumetric 3d line of sight for interiors.

The most time-consuming and demanding art job is creating the 3d traversable levels. Coming from a 2D world where we could easily sketch out on grid paper where things are, you really have to throw that out the door and get into the 3D to see how things feel inside/outside buildings and how it looks in an isometric view with being able to turn the camera. There’s just a lot to consider, especially when you don’t want to make it a headache for the player. There’s also height to consider, where we want to establish a consistent feeling for the player as to how far they can leap across things, how tall cover states are, and so on. We sometimes wish we had an architect to help with the sci-fi city nature of it all. In the end, we landed on a design that featured self-contained city ‘blocks,’ sort of like the Barcelona’s grid layout atop a sea. This layout exclusively gets us everything we wanted in every map — verticality, roofs to jump on, outside storefronts to climb, interiors, bunkers, as well as the usual streets and roadways connecting everything. So its very comprehensive, but can be a challenging maze to interconnect places in a logical way.

EM: Whalenought Studios is largely a two person production, so while you take on different roles (animator and artist vs programmer and writer), you rely on each other and have to know a fair amount of what will impact each other when content decisions get made. With that in mind, how do you make the most efficient use of time, how do you schedule workflow, and what have been your biggest challenges, as a small studio?

HW: Time! The clock is always racing against us. We’re only two people on the development side of things. We obviously don’t know everything and want to make sure we’re using best practices, so R&D is necessary, but tough to budget for when deadlines are looming. Living and working together at home and not having ‘weekends’ really makes the development process more of a lifestyle than just a job, sometimes we go outside and realize it’s been three days since we left the house. We’ve found that it’s important to take time off once in a while, even though it’s hard to justify with a paycheck still far away, but otherwise our brains get mushy and we don’t work efficiently. So we go for a hike on one of the nearby mountains or make some stabs at gardening.

We see plenty of crowdfunded games not allocate those funds well and have to cut or just stop development. It’s heartbreaking to read their final posts. There’s a lot of pressure there, and you feel like it could be you if you’re not careful. You adapt though, and the excitement of being able to work together all day every day overcomes the stress of financial insecurity.

Fortunately, working side by side all day does make workflow extremely flexible. We’re pretty familiar with each other, of course, so we don’t have to ask stupid questions and can understand how long things take or what would be best for certain pipelines. If Joe needs a new tool for exporting maps he’d want to do immediately, I take a few minutes whipping that up. That stuff saves hours. Or when I am about to start development on a new system or mechanic, Joe can quickly shift art gears toward that to get it up and running.

Working on new systems and mechanics together is a real treat, it’s a realtime hybrid of art and programming all at once and creating some fun stuff on screen. Plus, working without any office politics or dealing with employees is a treasure in and of itself. I think we’re slowly becoming unemployable as we’ve accustomed to this the past 5 years. We have some guys helping with the OST and voice work for Copper Dreams that worked on Serpent, and they know us well and are just terrific to work with. We also have some internal testers we’ve chatted with about a lot of the ideas that have been fleshed out into the final game for the ruleset and mechanics, and they’ve been very helpful, and very patient, as we take quarter-years to complete some overhauls.

EM: The divide that exists between dreaming about a project and implementing a game is often a wide chasm due to technical hurdles, so how have you maintained a creative spirit while doing the often difficult legwork involved in asset creation, scripting, and coding? Additionally, as you look at the market your games are in, do you see the tools that are available to developers making it easier for enthusiasts to create compelling projects, or do we simply have more people realizing that they can potentially steer their own creative projects if they put in the time? As you look ahead, what do you see as game changers for the indie world?

HW: It’s not easy to maintain the original spark of that creative spirit when you’re doing several iterations on the same thing for so long. Our budget doesn’t allow for burnout time, so we keep going even when the spark comes and goes, but you quickly learn to trust the original plan and love it as you push through. Should that fail, you remind yourself you have ~1000 Kickstarter backers waiting for their rewards! It’s agonizing to have things planned out but needing months to see it through. Loving the design of everything and being able to play it is worth its weight in gold for us though.

For others out there wanting to create games, knowing the right tools to use and knowing what you’re good at always helps. We develop with our strengths in mind, so we allow extra time for what we really need and make quick pipelines for everything we know or are good at to streamline where we can. There will always be development of new and better software, so we find it best to just use what you’re comfortable with. We still run some old Macs because we have old licensed software on them that allows us to escape the monthly payments they usually burden owners with. Do they chug when we run 3D software? Definitely, it’s a relief seeing them just turn on. Do they get the job done? Absolutely. You use what you have. As long as someone has the drive, they can accomplish anything, and the tools for making games are more accessible than ever and it’s objectively never been easier. Making something compelling, of course, is entirely different, and no set of tools or Unreal lighting will replace creativity and vision.

For game changers, we can’t really speak for a lot of genres besides ours, but what we hope to see is more games innovating on new gameplay concepts instead of just adding a snazzy feature to an already very established set of mechanics. CRPGs have somewhat stagnated since their boom in the 90s, and there could be more fun and clever ways of doing things than the tried and true formulas that happened to get popular back then. We fortunately are able to see more of that with indies, where they can break out into interesting territory without being creatively throttled by mainstream trends. We’ll always compare every CRPG to Fallout 1, we’re only human, but the genre certainly has room to grow outside of companion romances.

This was one of the best interviews I have ever read.Hannah did an interview: https://www.indiegraze.com/2017/09/25/interview-copper-dreams-hannah-williams/Interview: Copper Dreams’ Hannah Williams

on September 25, 2017

Copper Dreams transports players to a cyberpunk world of corporate war and horror far from Earth. The party-based isometric CRPG from Whalenought Studios employs unique, nuanced mechanics, and I chatted with dev Hannah Williams on the novelties of the project.

Erik Meyer: The release of games like Fallout, Diablo, and Ultima Online in the ’90s established isometric RPGs as a genre, but recent projects like No Truce With The Furies seek to expand standard conventions, such as dialogue. Your project uses a health system comprised of wounds in the place of a more abstract HP meter. Similarly, you have extensive sneak and weapons options systems. What other novel features and content do you see yourselves adding to Copper Dreams? What do you see yourselves implementing that you haven’t seen done elsewhere?

Hannah Williams: The heart and soul of Copper Dreams has always been creating a cozy, p&p roleplaying experience. A comfortable playground that allows you to approach the world as you would in a tabletop game, a ruleset that won’t hamstring your adventure by limiting your tools to those fed through specific dialogue options or one-note item uses. When an RPG does just that, rationing out your actions or even suddenly gifting you a narrative tool that allows you to do something that isn’t possible in game mechanics, it takes away the joy of actually roleplaying without being told what to do. Partially because the game designer spoon-fed you your actions like they did the narrative, but also because it also creates a sense of disorientation. Dice are rolled and actions are performed on the result, that’s a great start, but beyond that there’s a lot we wanted to rethink what a player has control of and what to do with it.

Here’s an example: I’m talking to a guard and I pick option A to palm him five gold coins so he’ll let me pass unmolested. Neat! Glad I didn’t have to stab him, he looked like he had a nice family at home waiting for him. But wait, can I do that with anyone? I never got that bribe option in dialogue before. Why did it pop up with him and not the now-dead guard downstairs? Was one less important on my narrative path? This one has a red vest, does that mean something? Did a writer get distracted and forget to add the dialogue option in before? Was there a secret charisma roll that I finally passed? Am I overthinking this? I’m scared, help! I wish I just had a button that let’s me try to bribe someone whenever I want to!

Most players, of course, are used to a bribe option popping up in dialogue and don’t need to dig out their smelling salts when it happens, but you get the idea. If you give a player all their tools to be used at will, it makes them feel like they can do anything they want, and also gives a sense of security, despite running around in an hostile environment, because you always know what your options are. If you want to try to bribe the final boss, by all means, give it a shot. If you want to bribe a chicken, do that too. Making the DM miserable is mostly what p&p is about, and the least we could do is give the player the freedom to do that to us.

The challenge of this is creating all these tools for players to use at will. Manually jumping over obstacles instead of clicking their hit box to disable them, climbing a roof for height advantage, dropping to a crouch to avoid a missile, dragging cigarettes out of your backpack to an NPC so they will spill their secrets, using your crossbow like a hammer when you’re out of bolts or just throwing it against the wall to make noise. These are the kind of things that we think create that cozy tabletop experience, and what will make our ruleset feel different.

EM: You ran a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Copper Dreams, but this isn’t your first Kickstarter, as you already had Serpent in the Staglands under your belts. What kinds of things did you learn from your previous projects and crowdfunding efforts that informed your process this go-around, and what have the community responses been like?

HW: Our Kickstarter community has always been a true delight in the experience of creating games. We are pretty introverted people, and when we started the company the idea of building a community was quite frankly terrifying. Most 13 year olds have more Twitter followers than we do. But then we took Serpent in the Staglands to Kickstarter, and suddenly there were people talking to us! And giving us ideas and suggestions! It was wonderful. Not just because no one should develop a game in a bubble, but just being digitally surrounded by people who love CRPGs was great. Even when they’re disappointed in you, it’s really great having people along for the ride to explore the possibilities of the best genre of computer games.

We had a lot of repeat backers from Serpent to Copper Dreams, and it’s been exciting to continue to see their comments and hear from them. As a two-person team, we think people know they are getting a very authored experience, a personalized product that comes from just two people creating all the art, writing, and gameplay. All that takes time though, and we learned from Serpent that we needed to allocate more time to ensure that all the ruleset and gameplay connections are working properly. So we’d like to get more feedback from our Kickstarter backers when we’re ready, but thus far they’ve been very supportive and most of all, very patient.

EM: I’m interested in the game’s freedom of movement, including vertical structures, which have often been tricky for isometric projects. What led to your decision to unite the buildings and locations of a particular district as one navigable space (as opposed to separately loaded areas), and what kinds of challenges have you faced in making movement through different areas feel intuitive?

HW: Vertical movement was our our particular obsession for a lot of this, besides tuning the tick/tile system. It’s high risk, because we were new to 3D and there are a ton of level design and programming challenges involved, but also high reward, because who doesn’t want to run around rooftops and climb walls and evade enemies by careening off of tall buildings?

It also felt necessary for that tabletop experience we’re gunning for. If you’re playing a p&p game and spot-check a tripwire, you’d just step over it, or roll to. Most isometric games fall prey to the nature of point n’ clicking, not easily allowing that, so you’d have to instead roll to disarm it or navigate around it. For non-grid based games that convey a level of ‘freedom’, that seems like phoning it in. Or if you want height advantage and you see a crate or short roof, you should just climb it. With the tile-based system we were able to allow this freedom without the need for any hand-eye coordination or reflexes. Moving in and out of buildings with a rotatable camera is important too. It adds a layer of excitement to seamlessly sneaking and getting into combat throughout the city that map loading wouldn’t allow for. Jumping outside a building window onto a lower roof to try to lose some guards chasing you is fun and gives you a lot of freedom. If you were playing a tabletop game, a DM wouldn’t say the guards lose you because you’re now in a new map.

The verticality we had envisioned has certainly been tough to implement, stirring emotions ranging from sheer panic to total excitement as we’ve evolved our systems for creating levels and seamless experiences when roofs or whole buildings that are blocking you need to disappear, or you run up staircases to a new floor and new content needs to be ready for you. If a roof disappears, is there a fog of war? Is it just a slice downward, or a big hole? They are questions asking how much do we want the player to see how the sausage was made, right? If we just chop roofs off or something, players can see how arbitrarily maps are designed. How can we make that vertical transition within a building not abrupt? How much needs to disappear so you can shoot someone at the end of a hallway? Have other isometric games done this (a few), and did they do it well (eh)? These are questions we’ve grappled with, and they’ve definitely been a challenge, but we’re actually very happy with how everything was solved.

EM: The game includes a multitude of factions, from The Mayflower Initiative to Agro-Fax and The Faith, each with different strengths and goals, to speak to the unique lore you’ve created as part of the development process. As a cyberpunk off-world dystopian setting, what elements have become the core of the experience you’re providing, and what kinds of things have you had to leave out?

HW: To get a feel for the experience, we like to picture a stranded Vietnam soldier behind enemy lines, slapping bandages on his wounds, constantly fighting ammo scarcity, confused, and just hoping he makes it through the night. Then take that solider, set him under some neon glowing lights and screw a few tinfoil hats on him and you have Copper Dreams.

The city itself is stamped with the distrust and suspicion bred by the warring syndicates. While the city is populated, the citizens are not on your side, because no one is on their side, and will rat you out if you’re acting fishy. They are frightened of the syndicates and broken down by the day to day difficulties of survival amongst scarce resources and constant faction fighting. You’ve got your bounty and a gun, and you’re the only person you can trust in the game. In the way of gameplay, that means solving mysteries yourself without a guide, patching yourself up, and bribing and making relationships with those you think you can trust. The premise of how people on the colony feed (and heal) themselves is also explored in the campaign setting, and while it’s fun and easy to side-eye our failing Big Pharma-based medicinal lifestyle today, it’s a very cyberpunk appropriate theme that’s interesting to explore.

Our original concept for the Kickstarter was always pretty narrow, we always envisioned the game as a ‘one-shot’ campaign, which in this case meant something compact that you could try with different play-throughs and different randomized content in a more city-simulation based campaign. The core systems of the playground were already pretty vast as they were, so we haven’t really left anything out, fortunately, but haven’t needed to add much more in than we had planned. Mostly, we just focused on iterating on what we had planned for.

EM: You incorporate a wait period into the turn-based combat system, meaning actions don’t execute immediately and can be interrupted. Can you speak a bit more to the genesis of this mechanic and how it translates to both small group (one-on-one fighting, for example) and large group (a bar brawl) encounters? How do you see players and NPCs anticipating enemy actions via this time element, and what added dimensions come with it, from a tactical point of view?

HW: This turn-time feature is really the crux of the game system and has been in flux since the Kickstarter. There’s been a lot of iterating. We wanted to do a turn-based system that is less abstract than the traditional model, where attacks take time and you can interrupt each other. It started with more of a combat timeline, represented in seconds, where character icons would travel across it while they performed their turn. They could get stopped on it, or when it finished they’d be prompted to do their next turn.

This was fun but had flaws. The time-based element was too arbitrary and became frustrating to try to compare between characters during combat. Eventually, we got rid of the actual representation of time in seconds and just had ‘ticks’ evolving into this now step-by-step turn based model. These ticks represent how long something takes, a certain attack might take 3 to prep, and 2 to recover from, where moving a certain distance might just take 4. If you get hit, you add more ‘hit’ ticks, which you have to wait through to get back to your action. Then there’s a tick to tile relationship as well, where you can see how many tiles you can cover while moving in the next tick, or how many tiles a bullet will pass through during one.

The beauty of the simulationist-based combat and ruleset is that things will play out largely how you’d expect them to. If there’s enough people on the screen, it turns into a bullet hell, but because it’s still turn-based, you have time to consider your tactics and adjust to the number of people you’re fighting and their abilities and strategies. Players (should) and NPCs will be seeking cover as much as they can to start with, as the life of characters can be quite limited. One-on-one combat gives you an easier opportunity to get the jump on an enemy or have a very dedicated shootout with each of you cat-and-mousing in and out of cover if you didn’t kill them stealthily or something. Since enemies can often be dispatched easily, other simulated aspects like the noise weapons make, calling for backup, or running for cover make engagements more interesting. There’s nothing stopping a player from sneaking around or instant killing anyone if they set up a roll nicely. There is no omnipresent AI for enemies, they individually read player location and actions based on your current position, stance and knowledge of what has passed. Different enemies could have different last known positions of where you might be, but alerting one in the presence of another would alert both to your location (or general direction). So gaming their senses is certainly part of the tactics, as you would in a stealth game.

To help show all this, players can anticipate enemy actions through the ticks that show up after an enemy chooses an action, and plan accordingly during their turns. If you see that they’re going to do something in 5 ticks, you can pick an action that takes less time, although potentially reducing your hit chance roll at the price of speed. We have a lot of indicators letting players know when bullets are coming and the direction someone is moving, so when that bullet-hell game happens, you can duck, crawl, and run to avoid what you can to get to more cover.

EM: In terms of in-game 3D assets, I note that the character models are low-poly and stylized by way of careful skinning, and as we view the game from afar, the world has a consistent feel. In terms of art direction and creation, what have been key goals and guiding factors? Do you run into hardware/game engine limitations? What ends up demanding the majority of your time?

HW: Our goal was definitely to custom design everything ourselves to make sure we could create a look of stylized consistency. Glad you think that’s coming through! We’re always tweaking the visuals to get it just right with everything. The game started with pixel art characters (playing with what we knew), but that’s evolved into sketchy palette-knife-like character textures with color blocked, chunkier models. It’s supposed to be abstract and stylized enough for a player to use their imagination to fill in some blanks. We loved that about 2D pixel art and aimed to do the same in 3D, and this just sort of naturally evolved as we took more stabs at it.

With a style like this, hardware was never really an issue. Our direction was never the Icarus of ‘realism,’ so it was just a great bonus that our chosen art style also leaves a small footprint. It does leave room for some of our more intensive systems, like the volumetric 3d line of sight for interiors.

The most time-consuming and demanding art job is creating the 3d traversable levels. Coming from a 2D world where we could easily sketch out on grid paper where things are, you really have to throw that out the door and get into the 3D to see how things feel inside/outside buildings and how it looks in an isometric view with being able to turn the camera. There’s just a lot to consider, especially when you don’t want to make it a headache for the player. There’s also height to consider, where we want to establish a consistent feeling for the player as to how far they can leap across things, how tall cover states are, and so on. We sometimes wish we had an architect to help with the sci-fi city nature of it all. In the end, we landed on a design that featured self-contained city ‘blocks,’ sort of like the Barcelona’s grid layout atop a sea. This layout exclusively gets us everything we wanted in every map — verticality, roofs to jump on, outside storefronts to climb, interiors, bunkers, as well as the usual streets and roadways connecting everything. So its very comprehensive, but can be a challenging maze to interconnect places in a logical way.

EM: Whalenought Studios is largely a two person production, so while you take on different roles (animator and artist vs programmer and writer), you rely on each other and have to know a fair amount of what will impact each other when content decisions get made. With that in mind, how do you make the most efficient use of time, how do you schedule workflow, and what have been your biggest challenges, as a small studio?

HW: Time! The clock is always racing against us. We’re only two people on the development side of things. We obviously don’t know everything and want to make sure we’re using best practices, so R&D is necessary, but tough to budget for when deadlines are looming. Living and working together at home and not having ‘weekends’ really makes the development process more of a lifestyle than just a job, sometimes we go outside and realize it’s been three days since we left the house. We’ve found that it’s important to take time off once in a while, even though it’s hard to justify with a paycheck still far away, but otherwise our brains get mushy and we don’t work efficiently. So we go for a hike on one of the nearby mountains or make some stabs at gardening.

We see plenty of crowdfunded games not allocate those funds well and have to cut or just stop development. It’s heartbreaking to read their final posts. There’s a lot of pressure there, and you feel like it could be you if you’re not careful. You adapt though, and the excitement of being able to work together all day every day overcomes the stress of financial insecurity.

Fortunately, working side by side all day does make workflow extremely flexible. We’re pretty familiar with each other, of course, so we don’t have to ask stupid questions and can understand how long things take or what would be best for certain pipelines. If Joe needs a new tool for exporting maps he’d want to do immediately, I take a few minutes whipping that up. That stuff saves hours. Or when I am about to start development on a new system or mechanic, Joe can quickly shift art gears toward that to get it up and running.

Working on new systems and mechanics together is a real treat, it’s a realtime hybrid of art and programming all at once and creating some fun stuff on screen. Plus, working without any office politics or dealing with employees is a treasure in and of itself. I think we’re slowly becoming unemployable as we’ve accustomed to this the past 5 years. We have some guys helping with the OST and voice work for Copper Dreams that worked on Serpent, and they know us well and are just terrific to work with. We also have some internal testers we’ve chatted with about a lot of the ideas that have been fleshed out into the final game for the ruleset and mechanics, and they’ve been very helpful, and very patient, as we take quarter-years to complete some overhauls.

EM: The divide that exists between dreaming about a project and implementing a game is often a wide chasm due to technical hurdles, so how have you maintained a creative spirit while doing the often difficult legwork involved in asset creation, scripting, and coding? Additionally, as you look at the market your games are in, do you see the tools that are available to developers making it easier for enthusiasts to create compelling projects, or do we simply have more people realizing that they can potentially steer their own creative projects if they put in the time? As you look ahead, what do you see as game changers for the indie world?

HW: It’s not easy to maintain the original spark of that creative spirit when you’re doing several iterations on the same thing for so long. Our budget doesn’t allow for burnout time, so we keep going even when the spark comes and goes, but you quickly learn to trust the original plan and love it as you push through. Should that fail, you remind yourself you have ~1000 Kickstarter backers waiting for their rewards! It’s agonizing to have things planned out but needing months to see it through. Loving the design of everything and being able to play it is worth its weight in gold for us though.

For others out there wanting to create games, knowing the right tools to use and knowing what you’re good at always helps. We develop with our strengths in mind, so we allow extra time for what we really need and make quick pipelines for everything we know or are good at to streamline where we can. There will always be development of new and better software, so we find it best to just use what you’re comfortable with. We still run some old Macs because we have old licensed software on them that allows us to escape the monthly payments they usually burden owners with. Do they chug when we run 3D software? Definitely, it’s a relief seeing them just turn on. Do they get the job done? Absolutely. You use what you have. As long as someone has the drive, they can accomplish anything, and the tools for making games are more accessible than ever and it’s objectively never been easier. Making something compelling, of course, is entirely different, and no set of tools or Unreal lighting will replace creativity and vision.

For game changers, we can’t really speak for a lot of genres besides ours, but what we hope to see is more games innovating on new gameplay concepts instead of just adding a snazzy feature to an already very established set of mechanics. CRPGs have somewhat stagnated since their boom in the 90s, and there could be more fun and clever ways of doing things than the tried and true formulas that happened to get popular back then. We fortunately are able to see more of that with indies, where they can break out into interesting territory without being creatively throttled by mainstream trends. We’ll always compare every CRPG to Fallout 1, we’re only human, but the genre certainly has room to grow outside of companion romances.

This was one of the best interviews I have ever read.Hannah did an interview: https://www.indiegraze.com/2017/09/25/interview-copper-dreams-hannah-williams/Interview: Copper Dreams’ Hannah Williams

on September 25, 2017

Copper Dreams transports players to a cyberpunk world of corporate war and horror far from Earth. The party-based isometric CRPG from Whalenought Studios employs unique, nuanced mechanics, and I chatted with dev Hannah Williams on the novelties of the project.

Erik Meyer: The release of games like Fallout, Diablo, and Ultima Online in the ’90s established isometric RPGs as a genre, but recent projects like No Truce With The Furies seek to expand standard conventions, such as dialogue. Your project uses a health system comprised of wounds in the place of a more abstract HP meter. Similarly, you have extensive sneak and weapons options systems. What other novel features and content do you see yourselves adding to Copper Dreams? What do you see yourselves implementing that you haven’t seen done elsewhere?

Hannah Williams: The heart and soul of Copper Dreams has always been creating a cozy, p&p roleplaying experience. A comfortable playground that allows you to approach the world as you would in a tabletop game, a ruleset that won’t hamstring your adventure by limiting your tools to those fed through specific dialogue options or one-note item uses. When an RPG does just that, rationing out your actions or even suddenly gifting you a narrative tool that allows you to do something that isn’t possible in game mechanics, it takes away the joy of actually roleplaying without being told what to do. Partially because the game designer spoon-fed you your actions like they did the narrative, but also because it also creates a sense of disorientation. Dice are rolled and actions are performed on the result, that’s a great start, but beyond that there’s a lot we wanted to rethink what a player has control of and what to do with it.

Here’s an example: I’m talking to a guard and I pick option A to palm him five gold coins so he’ll let me pass unmolested. Neat! Glad I didn’t have to stab him, he looked like he had a nice family at home waiting for him. But wait, can I do that with anyone? I never got that bribe option in dialogue before. Why did it pop up with him and not the now-dead guard downstairs? Was one less important on my narrative path? This one has a red vest, does that mean something? Did a writer get distracted and forget to add the dialogue option in before? Was there a secret charisma roll that I finally passed? Am I overthinking this? I’m scared, help! I wish I just had a button that let’s me try to bribe someone whenever I want to!

Most players, of course, are used to a bribe option popping up in dialogue and don’t need to dig out their smelling salts when it happens, but you get the idea. If you give a player all their tools to be used at will, it makes them feel like they can do anything they want, and also gives a sense of security, despite running around in an hostile environment, because you always know what your options are. If you want to try to bribe the final boss, by all means, give it a shot. If you want to bribe a chicken, do that too. Making the DM miserable is mostly what p&p is about, and the least we could do is give the player the freedom to do that to us.

The challenge of this is creating all these tools for players to use at will. Manually jumping over obstacles instead of clicking their hit box to disable them, climbing a roof for height advantage, dropping to a crouch to avoid a missile, dragging cigarettes out of your backpack to an NPC so they will spill their secrets, using your crossbow like a hammer when you’re out of bolts or just throwing it against the wall to make noise. These are the kind of things that we think create that cozy tabletop experience, and what will make our ruleset feel different.

EM: You ran a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund Copper Dreams, but this isn’t your first Kickstarter, as you already had Serpent in the Staglands under your belts. What kinds of things did you learn from your previous projects and crowdfunding efforts that informed your process this go-around, and what have the community responses been like?

HW: Our Kickstarter community has always been a true delight in the experience of creating games. We are pretty introverted people, and when we started the company the idea of building a community was quite frankly terrifying. Most 13 year olds have more Twitter followers than we do. But then we took Serpent in the Staglands to Kickstarter, and suddenly there were people talking to us! And giving us ideas and suggestions! It was wonderful. Not just because no one should develop a game in a bubble, but just being digitally surrounded by people who love CRPGs was great. Even when they’re disappointed in you, it’s really great having people along for the ride to explore the possibilities of the best genre of computer games.

We had a lot of repeat backers from Serpent to Copper Dreams, and it’s been exciting to continue to see their comments and hear from them. As a two-person team, we think people know they are getting a very authored experience, a personalized product that comes from just two people creating all the art, writing, and gameplay. All that takes time though, and we learned from Serpent that we needed to allocate more time to ensure that all the ruleset and gameplay connections are working properly. So we’d like to get more feedback from our Kickstarter backers when we’re ready, but thus far they’ve been very supportive and most of all, very patient.

EM: I’m interested in the game’s freedom of movement, including vertical structures, which have often been tricky for isometric projects. What led to your decision to unite the buildings and locations of a particular district as one navigable space (as opposed to separately loaded areas), and what kinds of challenges have you faced in making movement through different areas feel intuitive?

HW: Vertical movement was our our particular obsession for a lot of this, besides tuning the tick/tile system. It’s high risk, because we were new to 3D and there are a ton of level design and programming challenges involved, but also high reward, because who doesn’t want to run around rooftops and climb walls and evade enemies by careening off of tall buildings?

It also felt necessary for that tabletop experience we’re gunning for. If you’re playing a p&p game and spot-check a tripwire, you’d just step over it, or roll to. Most isometric games fall prey to the nature of point n’ clicking, not easily allowing that, so you’d have to instead roll to disarm it or navigate around it. For non-grid based games that convey a level of ‘freedom’, that seems like phoning it in. Or if you want height advantage and you see a crate or short roof, you should just climb it. With the tile-based system we were able to allow this freedom without the need for any hand-eye coordination or reflexes. Moving in and out of buildings with a rotatable camera is important too. It adds a layer of excitement to seamlessly sneaking and getting into combat throughout the city that map loading wouldn’t allow for. Jumping outside a building window onto a lower roof to try to lose some guards chasing you is fun and gives you a lot of freedom. If you were playing a tabletop game, a DM wouldn’t say the guards lose you because you’re now in a new map.

The verticality we had envisioned has certainly been tough to implement, stirring emotions ranging from sheer panic to total excitement as we’ve evolved our systems for creating levels and seamless experiences when roofs or whole buildings that are blocking you need to disappear, or you run up staircases to a new floor and new content needs to be ready for you. If a roof disappears, is there a fog of war? Is it just a slice downward, or a big hole? They are questions asking how much do we want the player to see how the sausage was made, right? If we just chop roofs off or something, players can see how arbitrarily maps are designed. How can we make that vertical transition within a building not abrupt? How much needs to disappear so you can shoot someone at the end of a hallway? Have other isometric games done this (a few), and did they do it well (eh)? These are questions we’ve grappled with, and they’ve definitely been a challenge, but we’re actually very happy with how everything was solved.

EM: The game includes a multitude of factions, from The Mayflower Initiative to Agro-Fax and The Faith, each with different strengths and goals, to speak to the unique lore you’ve created as part of the development process. As a cyberpunk off-world dystopian setting, what elements have become the core of the experience you’re providing, and what kinds of things have you had to leave out?

HW: To get a feel for the experience, we like to picture a stranded Vietnam soldier behind enemy lines, slapping bandages on his wounds, constantly fighting ammo scarcity, confused, and just hoping he makes it through the night. Then take that solider, set him under some neon glowing lights and screw a few tinfoil hats on him and you have Copper Dreams.

The city itself is stamped with the distrust and suspicion bred by the warring syndicates. While the city is populated, the citizens are not on your side, because no one is on their side, and will rat you out if you’re acting fishy. They are frightened of the syndicates and broken down by the day to day difficulties of survival amongst scarce resources and constant faction fighting. You’ve got your bounty and a gun, and you’re the only person you can trust in the game. In the way of gameplay, that means solving mysteries yourself without a guide, patching yourself up, and bribing and making relationships with those you think you can trust. The premise of how people on the colony feed (and heal) themselves is also explored in the campaign setting, and while it’s fun and easy to side-eye our failing Big Pharma-based medicinal lifestyle today, it’s a very cyberpunk appropriate theme that’s interesting to explore.

Our original concept for the Kickstarter was always pretty narrow, we always envisioned the game as a ‘one-shot’ campaign, which in this case meant something compact that you could try with different play-throughs and different randomized content in a more city-simulation based campaign. The core systems of the playground were already pretty vast as they were, so we haven’t really left anything out, fortunately, but haven’t needed to add much more in than we had planned. Mostly, we just focused on iterating on what we had planned for.

EM: You incorporate a wait period into the turn-based combat system, meaning actions don’t execute immediately and can be interrupted. Can you speak a bit more to the genesis of this mechanic and how it translates to both small group (one-on-one fighting, for example) and large group (a bar brawl) encounters? How do you see players and NPCs anticipating enemy actions via this time element, and what added dimensions come with it, from a tactical point of view?

HW: This turn-time feature is really the crux of the game system and has been in flux since the Kickstarter. There’s been a lot of iterating. We wanted to do a turn-based system that is less abstract than the traditional model, where attacks take time and you can interrupt each other. It started with more of a combat timeline, represented in seconds, where character icons would travel across it while they performed their turn. They could get stopped on it, or when it finished they’d be prompted to do their next turn.

This was fun but had flaws. The time-based element was too arbitrary and became frustrating to try to compare between characters during combat. Eventually, we got rid of the actual representation of time in seconds and just had ‘ticks’ evolving into this now step-by-step turn based model. These ticks represent how long something takes, a certain attack might take 3 to prep, and 2 to recover from, where moving a certain distance might just take 4. If you get hit, you add more ‘hit’ ticks, which you have to wait through to get back to your action. Then there’s a tick to tile relationship as well, where you can see how many tiles you can cover while moving in the next tick, or how many tiles a bullet will pass through during one.

The beauty of the simulationist-based combat and ruleset is that things will play out largely how you’d expect them to. If there’s enough people on the screen, it turns into a bullet hell, but because it’s still turn-based, you have time to consider your tactics and adjust to the number of people you’re fighting and their abilities and strategies. Players (should) and NPCs will be seeking cover as much as they can to start with, as the life of characters can be quite limited. One-on-one combat gives you an easier opportunity to get the jump on an enemy or have a very dedicated shootout with each of you cat-and-mousing in and out of cover if you didn’t kill them stealthily or something. Since enemies can often be dispatched easily, other simulated aspects like the noise weapons make, calling for backup, or running for cover make engagements more interesting. There’s nothing stopping a player from sneaking around or instant killing anyone if they set up a roll nicely. There is no omnipresent AI for enemies, they individually read player location and actions based on your current position, stance and knowledge of what has passed. Different enemies could have different last known positions of where you might be, but alerting one in the presence of another would alert both to your location (or general direction). So gaming their senses is certainly part of the tactics, as you would in a stealth game.

To help show all this, players can anticipate enemy actions through the ticks that show up after an enemy chooses an action, and plan accordingly during their turns. If you see that they’re going to do something in 5 ticks, you can pick an action that takes less time, although potentially reducing your hit chance roll at the price of speed. We have a lot of indicators letting players know when bullets are coming and the direction someone is moving, so when that bullet-hell game happens, you can duck, crawl, and run to avoid what you can to get to more cover.

EM: In terms of in-game 3D assets, I note that the character models are low-poly and stylized by way of careful skinning, and as we view the game from afar, the world has a consistent feel. In terms of art direction and creation, what have been key goals and guiding factors? Do you run into hardware/game engine limitations? What ends up demanding the majority of your time?

HW: Our goal was definitely to custom design everything ourselves to make sure we could create a look of stylized consistency. Glad you think that’s coming through! We’re always tweaking the visuals to get it just right with everything. The game started with pixel art characters (playing with what we knew), but that’s evolved into sketchy palette-knife-like character textures with color blocked, chunkier models. It’s supposed to be abstract and stylized enough for a player to use their imagination to fill in some blanks. We loved that about 2D pixel art and aimed to do the same in 3D, and this just sort of naturally evolved as we took more stabs at it.

With a style like this, hardware was never really an issue. Our direction was never the Icarus of ‘realism,’ so it was just a great bonus that our chosen art style also leaves a small footprint. It does leave room for some of our more intensive systems, like the volumetric 3d line of sight for interiors.

The most time-consuming and demanding art job is creating the 3d traversable levels. Coming from a 2D world where we could easily sketch out on grid paper where things are, you really have to throw that out the door and get into the 3D to see how things feel inside/outside buildings and how it looks in an isometric view with being able to turn the camera. There’s just a lot to consider, especially when you don’t want to make it a headache for the player. There’s also height to consider, where we want to establish a consistent feeling for the player as to how far they can leap across things, how tall cover states are, and so on. We sometimes wish we had an architect to help with the sci-fi city nature of it all. In the end, we landed on a design that featured self-contained city ‘blocks,’ sort of like the Barcelona’s grid layout atop a sea. This layout exclusively gets us everything we wanted in every map — verticality, roofs to jump on, outside storefronts to climb, interiors, bunkers, as well as the usual streets and roadways connecting everything. So its very comprehensive, but can be a challenging maze to interconnect places in a logical way.

EM: Whalenought Studios is largely a two person production, so while you take on different roles (animator and artist vs programmer and writer), you rely on each other and have to know a fair amount of what will impact each other when content decisions get made. With that in mind, how do you make the most efficient use of time, how do you schedule workflow, and what have been your biggest challenges, as a small studio?

HW: Time! The clock is always racing against us. We’re only two people on the development side of things. We obviously don’t know everything and want to make sure we’re using best practices, so R&D is necessary, but tough to budget for when deadlines are looming. Living and working together at home and not having ‘weekends’ really makes the development process more of a lifestyle than just a job, sometimes we go outside and realize it’s been three days since we left the house. We’ve found that it’s important to take time off once in a while, even though it’s hard to justify with a paycheck still far away, but otherwise our brains get mushy and we don’t work efficiently. So we go for a hike on one of the nearby mountains or make some stabs at gardening.

We see plenty of crowdfunded games not allocate those funds well and have to cut or just stop development. It’s heartbreaking to read their final posts. There’s a lot of pressure there, and you feel like it could be you if you’re not careful. You adapt though, and the excitement of being able to work together all day every day overcomes the stress of financial insecurity.

Fortunately, working side by side all day does make workflow extremely flexible. We’re pretty familiar with each other, of course, so we don’t have to ask stupid questions and can understand how long things take or what would be best for certain pipelines. If Joe needs a new tool for exporting maps he’d want to do immediately, I take a few minutes whipping that up. That stuff saves hours. Or when I am about to start development on a new system or mechanic, Joe can quickly shift art gears toward that to get it up and running.

Working on new systems and mechanics together is a real treat, it’s a realtime hybrid of art and programming all at once and creating some fun stuff on screen. Plus, working without any office politics or dealing with employees is a treasure in and of itself. I think we’re slowly becoming unemployable as we’ve accustomed to this the past 5 years. We have some guys helping with the OST and voice work for Copper Dreams that worked on Serpent, and they know us well and are just terrific to work with. We also have some internal testers we’ve chatted with about a lot of the ideas that have been fleshed out into the final game for the ruleset and mechanics, and they’ve been very helpful, and very patient, as we take quarter-years to complete some overhauls.

EM: The divide that exists between dreaming about a project and implementing a game is often a wide chasm due to technical hurdles, so how have you maintained a creative spirit while doing the often difficult legwork involved in asset creation, scripting, and coding? Additionally, as you look at the market your games are in, do you see the tools that are available to developers making it easier for enthusiasts to create compelling projects, or do we simply have more people realizing that they can potentially steer their own creative projects if they put in the time? As you look ahead, what do you see as game changers for the indie world?

HW: It’s not easy to maintain the original spark of that creative spirit when you’re doing several iterations on the same thing for so long. Our budget doesn’t allow for burnout time, so we keep going even when the spark comes and goes, but you quickly learn to trust the original plan and love it as you push through. Should that fail, you remind yourself you have ~1000 Kickstarter backers waiting for their rewards! It’s agonizing to have things planned out but needing months to see it through. Loving the design of everything and being able to play it is worth its weight in gold for us though.

For others out there wanting to create games, knowing the right tools to use and knowing what you’re good at always helps. We develop with our strengths in mind, so we allow extra time for what we really need and make quick pipelines for everything we know or are good at to streamline where we can. There will always be development of new and better software, so we find it best to just use what you’re comfortable with. We still run some old Macs because we have old licensed software on them that allows us to escape the monthly payments they usually burden owners with. Do they chug when we run 3D software? Definitely, it’s a relief seeing them just turn on. Do they get the job done? Absolutely. You use what you have. As long as someone has the drive, they can accomplish anything, and the tools for making games are more accessible than ever and it’s objectively never been easier. Making something compelling, of course, is entirely different, and no set of tools or Unreal lighting will replace creativity and vision.

For game changers, we can’t really speak for a lot of genres besides ours, but what we hope to see is more games innovating on new gameplay concepts instead of just adding a snazzy feature to an already very established set of mechanics. CRPGs have somewhat stagnated since their boom in the 90s, and there could be more fun and clever ways of doing things than the tried and true formulas that happened to get popular back then. We fortunately are able to see more of that with indies, where they can break out into interesting territory without being creatively throttled by mainstream trends. We’ll always compare every CRPG to Fallout 1, we’re only human, but the genre certainly has room to grow outside of companion romances.