Primordial Muses: Virginia Mishnun-Hardman

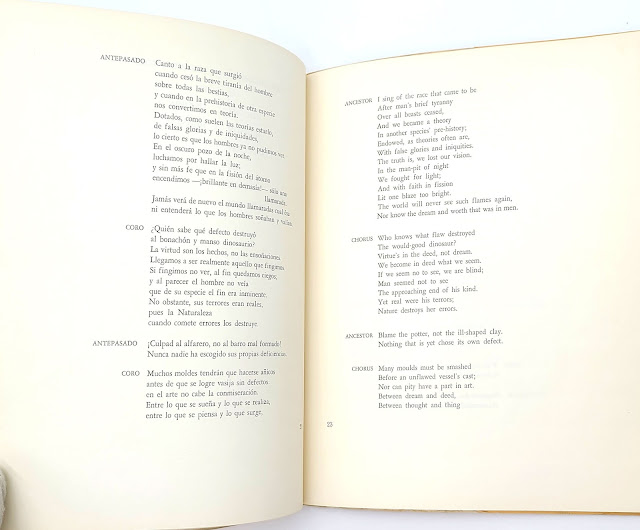

Between dream and deed,

Between thought and thing

Made real on the potter’s wheel,

The abyss is not less

Than between the living and unliving.

- Virginia Mishnun-Hardman, “The Inheritors”

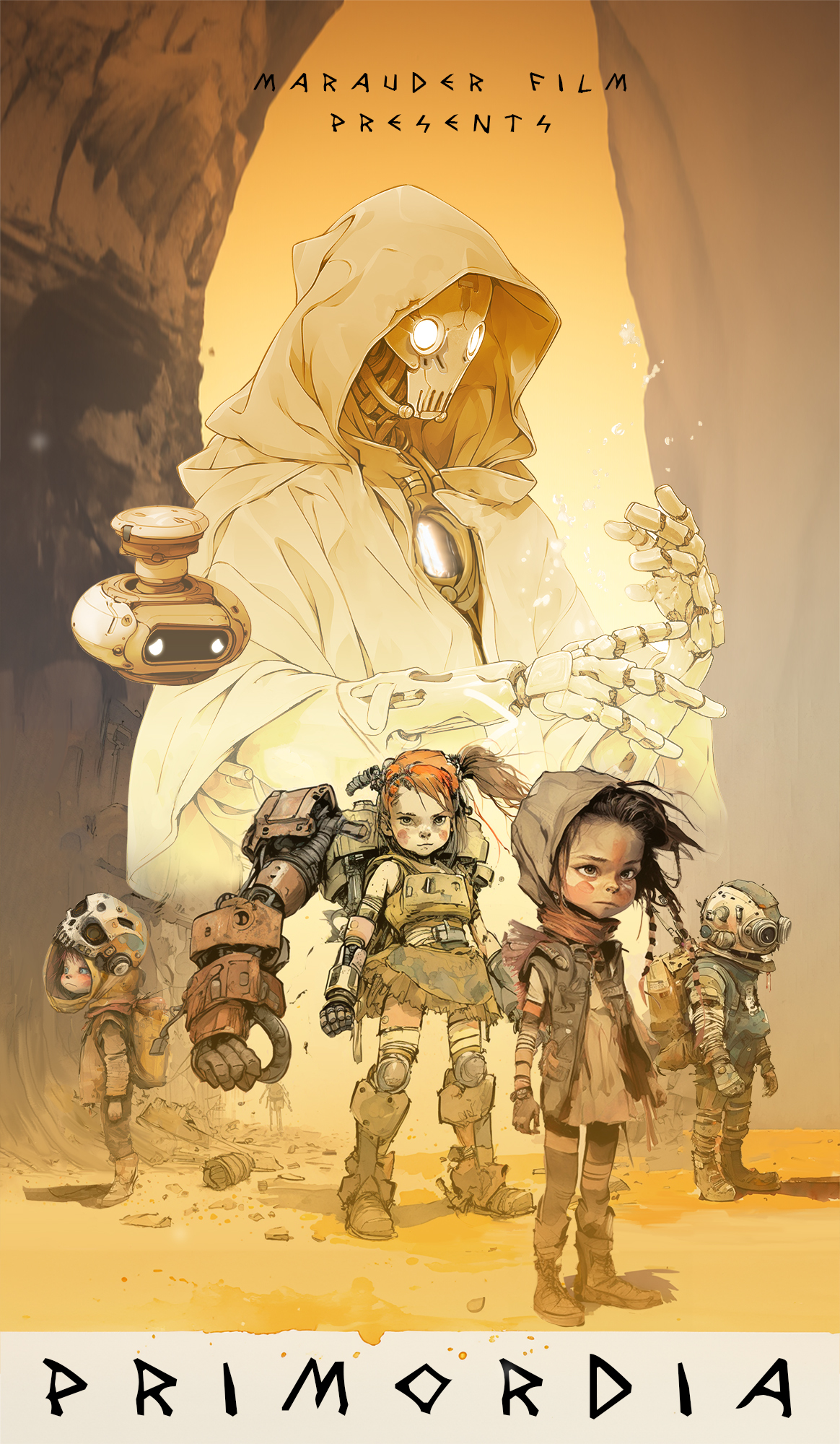

When

Primordia turned 10 years old, I

mentioned that I wanted to share some retrospective thoughts about making the game. Unfortunately, the press of life, family, work, and

Fallen Godskept me from diving in immediately. But a longtime fan of the game recently asked me where its themes of humanism, post-human inheritors, and dignity and defiance in the face of hopelessness came from. All of us who made the game, including James, Vic, Nathaniel, Dave, the voice actors, drew on our own experiences, and each of us had different muses. I thought it would be nice to talk about mine, and how they inspired the game’s writing and design.

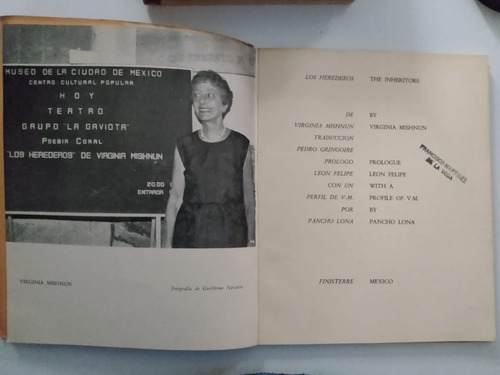

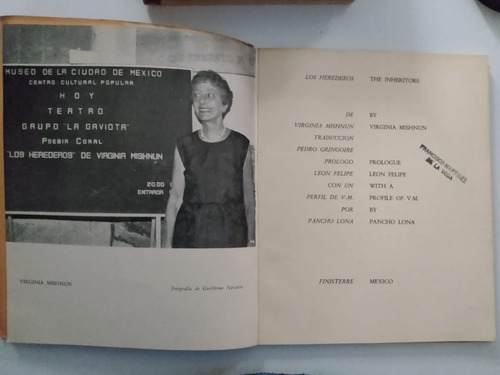

The first muse I want to talk about is my great aunt, the poet

Virginia Mishnun-Hardman.

To start with, wherefor and wherefrom Humanism? Well….

Aunt Virginia’s influence on the world, themes, story, and characters of

Primordia is something recognized from the very outset, when John Scalzi graciously hosted a “

Big Idea” about

Primordia on the day of the game’s release. Rather than just repeat that homage, I’d like to expand upon it, both with a bit more biography and with more of her poetry.

Virginia Mishnun was born around the turn of the 20th century and died at the turn of the 21st century. Her home was New York City, the ultimate metropolis, but she found welcome in Mexico City, Rockport, and Tel Aviv. A graduate of Hunter College and Columbia University, she passed through many trades in her life (including dance, reporting, editing, and social work). But she was foremost a poet and an activist. Her cause was humanity—meaning both the collective of our vast, flawed species, and that quality of ours that redeems those flaws. She was an advocate for refugees and the dispossessed (including as an editor of the International Rescue and Relief Committee

Bulletin during the Holocaust), for women, for

Native Americans, and for workers. Alongside her second husband,

J.B.S. Hardman, she worked in the labor movement.

After J.B.’s death in 1968, Virignia wrote the poem “Wait for Me”: “As all our lives you went ahead / To find new lands, / So now I’m briefly left behind once more / While you explore a shore I still can’t see / And I again cry, / ‘Wait—oh wait for me.’” But, by the grace of nature and nature’s god, she lingered not “briefly” but at length, and so was a part of my life for over two decades. It’s thanks to her that I’m a writer, and thanks to her that I wrote

Primordia.

As a poet, she published two anthologies (

The Inheritors and

Bright Winter), and many standalone poems in the United States, Mexico, and Israel. The anti-fascist Spanish poet

León Felipe called her “a consolation and a miracle.” The American philosopher and scholar

Maxine Greene celebrated Virginia’s “remarkable ability to render torment and isolation into a celebration of human life.” And the novelist and critic

Waldo Frank called her “the most living American poet since Hart Crane”—a line of praise that underscores the ephemeral nature of poets’ fame, since, but for that quotation, I wouldn’t know Hart Crane from Ichabod Crane.

My aunt was a fervent, lifelong socialist, but with equal fervor she despised the inhumanity and dishonesty of the Soviet Communists. When Stalin betrayed the cause of anti-fascism and made his pact with Hitler, she saw friends and allies from the labor movement turn on a dime, praising the same Fuhrer they had reviled days earlier. Anyone who has read Orwell knows the socialists’ sense of rage and betrayal at this about-face. As she told me years later, she saw good people hollowed by lies; they became “shells.” They had, she said, turned the poetic language of progress into empty sloganeering. That the USSR later helped demolish the Nazis never changed her view; hers was a socialism that had at its heart the conviction that human beings and human tragedy could never be reduced to “a statistic.” If, in these lessons she taught me, you recognize the roots of MetroMind and the shells that drag themselves through the Underworks, you would not be wrong.

Aunt Virginia’s socialist activism was her entree into science fiction because many science fiction authors of the late 19th and early 20th century used their novels as an extension of their progressive politics. On her bookshelves were first editions of H.G. Wells’s science fiction novels—alongside his socialist writings. So too did she have the science fiction of Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Joseph Conrad, Arthur Conan Doyle, and others. This is, of course, “respectable” science fiction, so typically bookstores stock such novels on the “Classics” shelf. But to Virginia, that was flat wrong. Respectability and enshrinement were a kind of tomb. Great books are “vital” precisely because they are “alive” and accessible.

It was from this perspective that she embraced, nurtured, sheltered, and encouraged my love of science fiction and fantasy. As is covered in the “Big Idea,” she was the rare adult who taught that “growing up” was a struggle against the loss of imagination rather than, as St. Paul wrote, a process of “put[ting] away childish things.” In her poem “Dreams In Age,” she wrote: “Like water colors / Erased by life’s deluge / Are the dreams of youth.” Her own life’s deluge had been torrential. But she helped shield the watercolors of my youthful dreams.

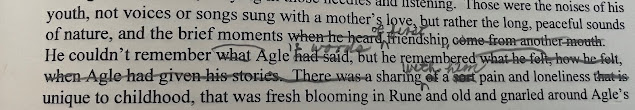

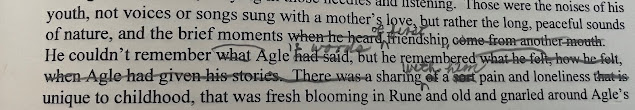

We told stories together. In one of the lower moments of my childhood, my family had moved across the country, I had left my friends behind, and I was subjected to a teacher who, among other things, forced me to write a letter to my parents apologizing for being stupid and incompetent at English. That same year Aunt Virginia sent me for Christmas a near-mint copy of

Bright Winter addressed to “Mark, dear fellow writer.” On the frontispiece she inscribed “a new poem”: “To be hunted.” “... oh, the terror of the / Poet, prey, destroyed again / And again ....” She did, indeed, know how “to render torment and isolation into a celebration of human life.”

Years later, in college, when I told her I had spent months writing a poem about Hector’s death beneath the walls of Troy, only to have my Classics professor dismiss it as worthless, she shot back a short note: “Let us pause to urinate / on the over-lauded laureate.” She knew what she was doing. As she said in “On Learning”: “They say / grief teaches. / But I learn faster / When joy’s the master.”

When I wrote a trio of science fiction stories in 2000, she found the core of each and helped me refine them all. One, “The Skinny Mnemonsyne,” features the first incarnation of the Underworks and its memory-less shells. Another was “

New Mansions,” and it established themes I’d later elaborate in

Primordia. No doubt inspired by “The Heart of Steel” arc in

Batman: The Animated Series, its premise is that a faction of humanity seeks to replace flawed politicians and judges with incorruptible robotic doppelgangers (foreshadowing

Primordia’s Arbiter, visually modeled off of

BTAS’s

H.A.R.D.A.C.). The protagonist is the first of these doppelgangers, a war veteran unaware of his own identity and programmed to venerate humanity (like Horatio/Horus). I was stumped by the ending until Virginia observed that, if he had been programmed to venerate humanity, he would destroy himself and the doppelganger scheme to spare mankind its downfall. Thus she sowed the seeds of the Horus’s sacrifice and Autonomous 8’s awakening in my

Primordia spin-off story “Fallen.” (Alas, despite Virginia’s best efforts, I don’t think “New Mansions” is a particularly good story….)

The last work of mine that Aunt Virginia edited was a 300-page manuscript of a fantasy novel I sent her in 2001, when she was in her nineties. With a claw-like hand tortured by arthritis and gout, she line edited every page in her shaky script.

On the first page (a prologue entitled “Upon the Web”), she stuck a Post-It note: “Between us, there is a web without end.” She died just two years later. She was, indeed, a “consolation and a miracle.”

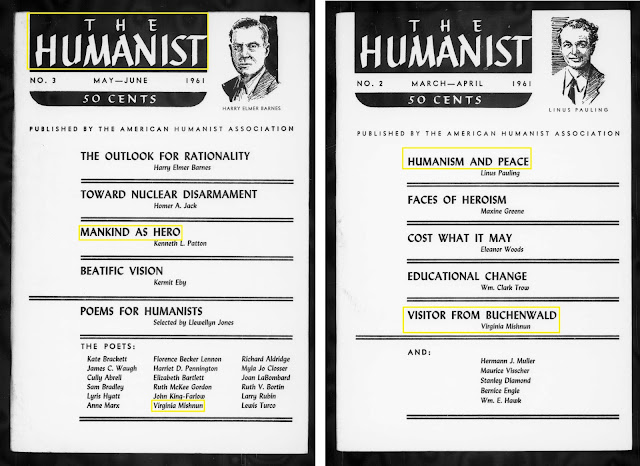

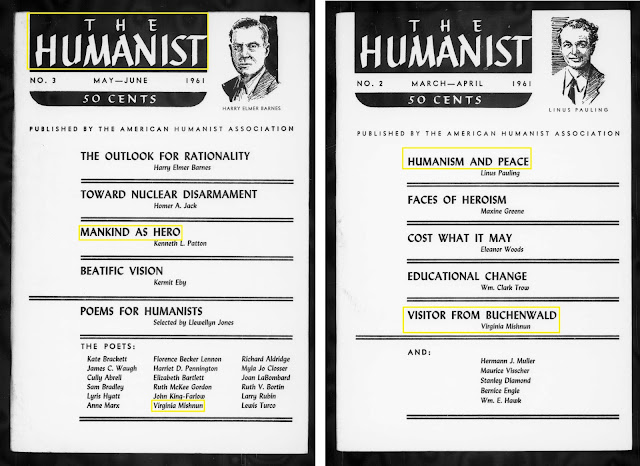

Virginia’s poetry is about love, loss, injustice, war, the Holocaust, violence against women, the act and art of creation, and hope. Her poem “A Visitor From Buchenwald” was published and regularly recited in New York, Rockport, Mexico City, and Tel Aviv, in English and Spanish.

But these respectable themes are embedded in the imagination, energy, and language of science fiction and, in particular, post-apocalyptic science fiction. In “In Time of Testing,” written after the death of her husband J.B. and in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Virginia imagines a post-apocalyptic landscape in which humanity gives way to machines. She tells of “the pizzicato of fat rats scurrying through / The wonderful garbage that was once a world.” And she asks, “Why use men when we can get the answers / from the do-it-themselves dream-proof machines? / After all, the Divine Engine will soon arrive. It was programmed / To appear at the end of the third act, which is where we’re at.” “Play computers? Let the computers play!” When she wrote that poem, first published in

John Herling’s Labor Letter in 1970, could she have imagined the unborn grand-nephew who would play computers and let the computers play, and tell the story of robots scurrying through the wonderful garbage that was once a world?

Above all, it was her post-apocalyptic poem “The Inheritors” that shaped

Primordia.

In the extraordinary essay “Poetry and People” that precedes “The Inheritors” in the collection of the same name, Virginia writes: “Both

Dr. Zhivago and

Last of the Just enlarge us, make us thrillingly aware of our own dormant capacities for living fully like compassionate humans, even in an inhuman world. They give us confidence that this species need not perish; that it can indeed transform itself, and in the transformation be more human than it yet has been. The overtones that reverberate long after the stories end are those of awful victory, suggesting that the unyielding assertion of individual humanity may be the only possible triumph in the present Twilight of Mankind.” In

Primordia, I strove to tell my own story about the “unyielding assertion of individual humanity,” a world in which “the species need not perish” even though it has vanished.

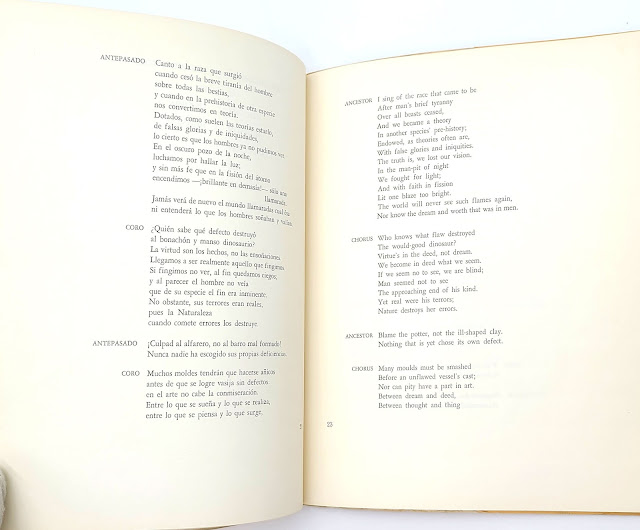

So too is Virginia’s poem set in a world destroyed by war, bereft of humanity, and left to our inheritors, to whom we are merely “a theory ... with false glories and iniquities.”

I sing of the race that came to be

After man’s brief tyranny

Over all beasts ceased,

And we became a theory

In another species’ pre-history;

Endowed, as theories often are,

With false glories and iniquities.

The truth is, we lost our vision.

In the man-pit of night

We fought for light;

And with faith in fission

Lit one blaze too bright.

The world will never see such flames again,

Nor know the dream and worth that was in men.

Anyone who has played

Primordia will feel at home in these verses, which helped shape the game’s characters, setting, lore, and themes. At one moment, two figures in “The Inheritors” muse and speculate about the humans’ demise—and, again, those familiar with

Primordia’s War of the Four Cities may hear the strains the game echoed. One character says, “One theory holds they had / Machines of such complexity / Only two brothers knew the key / To the whole world’s productivity.” The other answers, “The two were rivals; / Fighting one day, / Each slew the other.” Of the inheritors, we learn they pass “through immensities of galaxies and centuries, / Singing; with one small phrase forever altering / The endlessly unfolding theme / Of which each is briefly dreamer and dream.” Here is the seed of Civitas and its robots singing their eternal harmony. The poem wisely warns: “Greed beat the drum you followed, / Proud and blind into oblivion.”

But while “The Inheritors” had the most influence on

Primordia, other poems of hers helped create Horatio, Crispin, and other characters, as well as the setting. As for Horatio, consider, “Memo from Our Fathers”: “For faith / There are no substitutes. / The destroyers are always / Ready to attack. / But the builders know that their task is / To build; / That only when the wilderness within / Is stilled / Will the wilderness without / Move back.” This is, of course, Horatio’s arc: becoming a “builder” rather than a “destroyer,” and achieving this victory over the waste outside of him by first achieving victory over the waste inside of him. For the setting, there is the horrifying “No Last Waltz, A Requiem,” which depicts with nightmarish imagery what it is to destroy a world and leave behind a “dead planet.” There is “Two Ways,” which tells of how, “Drowning in the dry sands / Go the acquisitors....” And on the phonograph of

Primordia’s UNNIIC, you can hear the song “

Dreams of Green,” my homage to Virginia’s “Mimosa Tree”: “Under the green mimosa tree / How green the dream I dream of you.”

Of course, Virginia’s poems were by no means the only, or even the primary, influence on

Primordia’s world and story. I drew on my love of games like

Planescape: Torment and

Fallout, childhood cartoons like

The Challenge of the GoBots and

He-Man, books like

The Road by Cormac McCarthy and

City by Clifford Simak, movies like

Metropolis and

Wall-E, classics from Shakespeare and Milton, as well as countless other inspirations from life and art. Crispin, for instance, is not much different from my own normal snark, subject to James’s prodding and encouragement. Goliath is based on a giant sculpture (“

The Awakening”) that I would climb on as a kid. And so on. And of course Vic looked to the wasteland and cityscape of

Beneath a Steel Sky, the famous biomechanical style of H.R. Giger, and other influences. Nathaniel filled the world with music drawn from sources like Vangelis and

Wendy Carlos. Creating

Primordia was truly a team effort, where each of us wove our creativity into a unified whole. Much of our inspiration came from each other.

In her poem “Warnings,” my aunt wrote: “They lack a future / Who befoul the past.” Sometimes, the befoulers of the past manage to drag themselves quite far into the future. But here, as elsewhere, I trust my aunt’s wisdom. Her eyes were always on the future—one eye fearful, one eye hopeful—but she drew from the wealth of the past to face those fears and realize those hopes. She is, for me, part of that wealth. For that and for what it meant for

Primordia, I will be forever grateful.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)