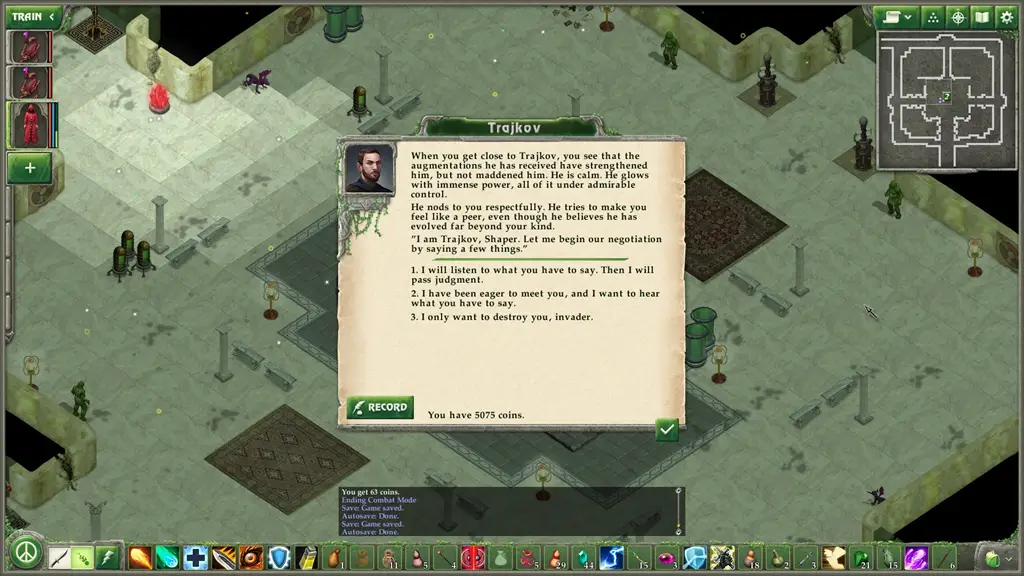

To this end, the Takers have allied themselves with the Sholai, a group of explorers from some distant land who have landed on Sucia. They’re humans, and they have also discovered the canisters full of magical goop – and they’re getting powers. Powers like yours, powers that are supposed to be reserved for the Shapers. Their leader, Trajkov, has sealed himself away in a chamber in a mountain containing a powerful Shaper tool – if you’re going to get to him, you’ll have to get stronger.

You don’t necessarily need to get

physically stronger, though (or magically, I guess).

Geneforge is adamant about letting you achieve one of several endings without ever shooting a fireball, much less even making a creature to aid you in battle. By upgrading your Leadership and Mechanics stats, you can unlock new dialogue options or bypass mechanical obstacles, allowing you access to parts of the world through routes other than fighting.

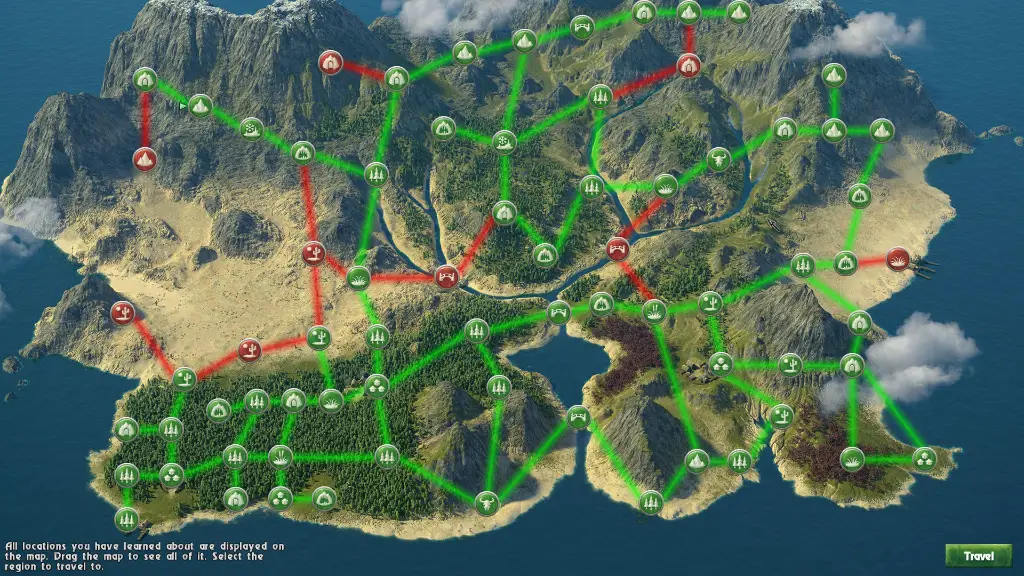

The likely version is you’ll end up using a combination of all three tactics to make your path across the island. The overworld of

Geneforge is made of interconnected area maps, and exploration is largely non-linear. In keeping with the older era of CRPG games, the game opens up really dangerous areas to you very early in the experience. It’s up to the player to realize that they aren’t going to be able to truck through the wastelands or get shot by ghosts for very long until they level up elsewhere on the island. Much of the western part of the map where you start the game is in fact incredibly high-level, and the vast expanse of initially-unexplorable land provides a lot of mystery as you chart the rest of the world.

Like

G1,

Mutagen has real-time map exploration, with an immediate switch into on-map turn-based combat. In

Mutagen, each unit gets 8 Action Points per round, to be used either to move, attack, or use special abilities.

G1 had the same Action Point system, but it didn’t show you a grid, so you had to estimate how many AP each movement action might use.

Mutagen has finally made the grid visible to the player, which also opened up a bunch of design space for the player and their creations.

The addition of the grid allows for new targetable abilities to be added into the game’s library of powers. Spray Crystal used to just hit a target and then the two nearest foes, but now it requires positioning your Shaper and lining up the shot, keeping your targets in the cone. Rods previously only contained buff effects that applied to all of your creations, but

Mutagen’s grid means that now there are a bunch of rods that can cast powerful destructive magics. My new favorite spell in

Mutagen is Airshock, a massive field of lightning that damages and stuns your enemies – it wouldn’t have worked without the new visualization system.

Similarly to rods, there are new crystals containing weaker versions of offensive Shaper spells. I found that the grid gave me confidence in using my items, and I didn’t just stockpile Spray Crystals and then sell them in town like I did in

G1. Overall,

Mutagen is much more generous than

G1 with the items you find throughout the world – I only shopped a few times, and I was never

too desperate for more healing pods.

Shapers aren’t the only ones who get to have fun with grids. All creations are now leveled up by selecting specific ability score upgrades and additional active and passive abilities, at the cost of more Essence. Many of these active abilities take the form of cones, but some creations have new single-target abilities that help them displace enemies or move across the battlefield. Creature types in

Mutagen are much more distinct than in previous

Geneforge games, even though there’s not much build diversity within a species. This differentiation of creatures, combined with the new spells, items, and grid tactics, makes combat in

Mutagen much more interesting than it was in

G1.

Creations no longer gain their own experience points like they did in the original

Geneforge series. This means that losing a minion in battle is less devastating, as you can just make another one of those creatures at the same level with the same stat picks. While this might be stressful for players who develop personal relationships to their creations, it fits the world-view of the young Shaper more closely: creations are disposable, and meant to be replaced.

This creation leveling rework does remove much of the control available in

G1, where you could stat each creation to your whims. In

Mutagen, each species has an unchanging list of abilities, and by the end of the game you’ll just be picking all of them every time you make a creation. While it does reduce player agency overall, it does provide an interesting conundrum in the midgame, when you might only have the Essence available for one upgrade – are you going to get a new attack, or a point of Magical Skill to boost what you already have?

Removing direct stat manipulation is particularly punishing in the early game, when you have poor control over your creations and they often get spooked and run from fights. In

G1 you could just dump points into Intelligence, but that’s not a creature stat in

Mutagen. Some folks on the Steam forum have done the math for how control levels in

Mutagen work, and right now it’s kind of broken: by increasing your Shaping skill for a type of creature (Fire, Battle, or Magic) you increase your control level. However, increasing that Shaping skill also gives that type of creation an extra level, returning the control level to the previous precarious number.

This is exacerbated by the number of creations you have, which stretch your focus and reduce your control over all of your minions, and whether or not you outlevel your creations (which you won’t for much of the early game, if you’re investing skill points in Shaping). Vogel says it’s working as intended, and I’m willing to admit that it fits the role-play of the game well: your character starts the game not even knowing how to make a creation, and they’re learning on their feet. Still, it makes an already-challenging game trickier than it needs to be, especially at the start of the experience.

The inventory rework balances out that early-game struggle, and makes equipping your character and carrying items much more accessible. Instead of the combined equipment + pack weight encumbrance system of the original

Geneforge series,

Mutagen only counts weight for your active equipment. To balance the potentially infinite weight in your inventory, you now only have 25 slots for bag items. This runs out quickly if you’re keeping lots of health pods, spores, crystals, and wands, so

Mutagen has also added a “junk bag” functionality, where you can keep anything you won’t need right away. Items in the junk bag can only be removed while you’re in a friendly city, so you can’t cheese the inventory system by keeping a bunch of usable items in the junk bag.

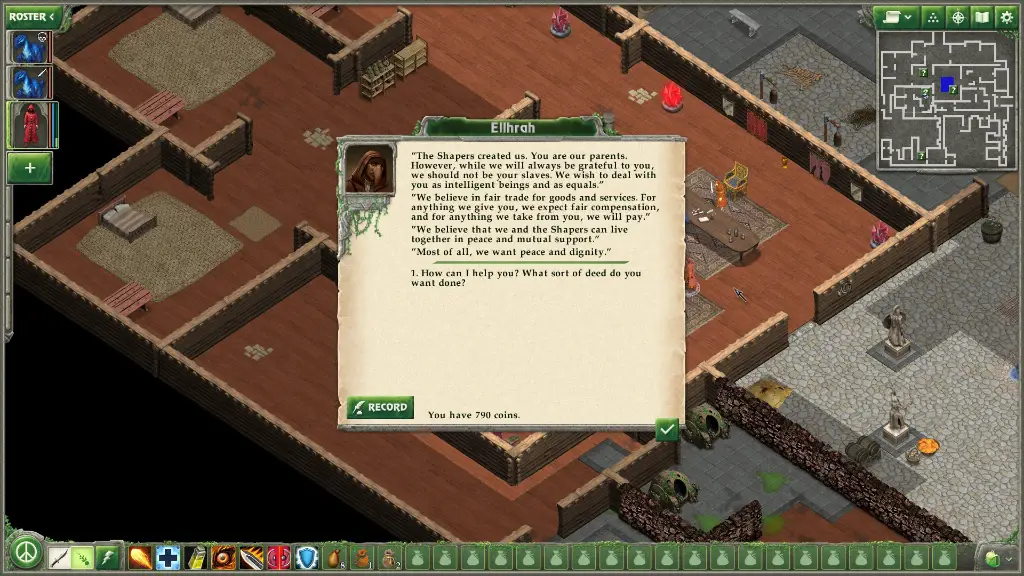

The writing in

Mutagen is excellent, with that classic dry wit gently masking the horror of the setting. One of Vogel’s best narrative tricks is just repeatedly hitting the player with second-person narration about how the character feels themself changing due to the canisters, which, when tied to progress across the world, makes it feel genuine. Slow but matter-of-fact reveals about the setting pull a lot of the game’s narrative weight, as the player “remembers” the various facets of Shaper society through the eyes of their character: the pigs-in-bowls that run whole laboratories, the dragons that Shapers stopped making because they were too smart, the creation gladiator arenas which were eventually banned and pushed underground.

And under all this, you’re learning details about the Sholai and their own fractured sectarianism. Details about what Trajkov does or doesn’t know are ferreted out, and allies reveal potential paths to his lair – the chamber of the Geneforge.

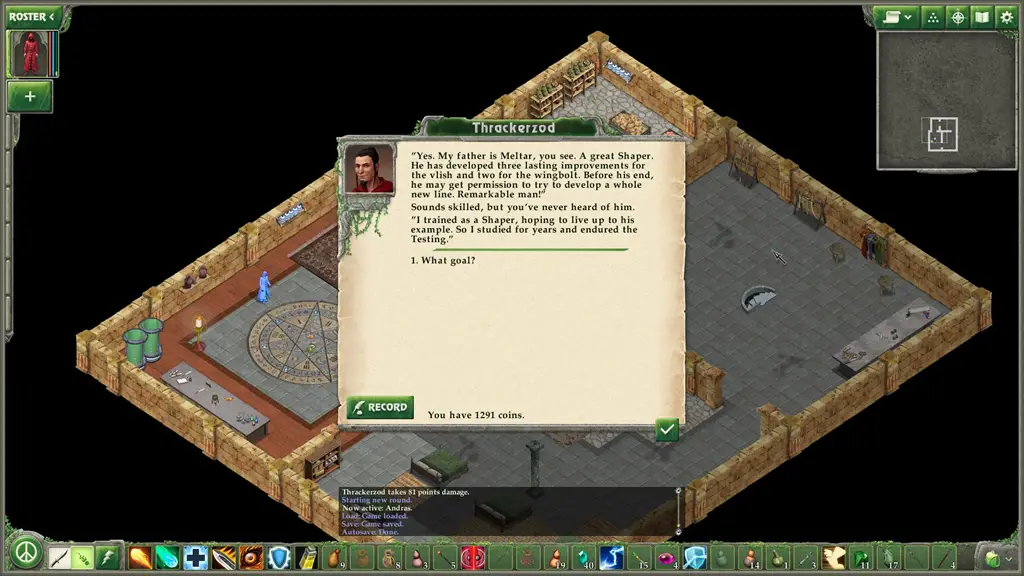

Mutagen has a new side storyline that surprised the hell out of me when I found it. About 14 hours in, I made my way to the Eastern Docks, a location I feel is a strong benchmark for being out of the beginning of the game. To my immense surprise, I found a new building on the map. A building with Shapers, from Terrestia, who weren’t trying to kill me. In fact, they couldn’t have cared less about me and the main plot if they’d tried – they’re intended as an example of Shapers who are already indoctrinated in the thought of their society, who mean to shape the laws of reality as master.

This gang is made up of the Shaper Thrackerzod, the Agent Arixy, and the Guardian Kevin. Thrackerzod’s father is Meltar, a name that didn’t ring any bells when I searched for it in other

Geneforge materials about the later games. In fact, the only evidence I could find of these characters existing pre-

Mutagen is from an

animated video made by a group of New Zealand teens. I reached out to Vogel on Twitter to ask about Thrackerzod’s origins, and received no reply. So that’s a fun mystery!

The end-game is gripping. there’s a distinct feeling when you’ve switched over from struggling against the endgame to fighting it on even footing, when you can summon dragons and big freaky grasshoppers and cut your way through the island. While getting to Trajkov doesn’t mark The End of The Game, it does mark The Middle of The End of The Game. You can choose to ally yourself with Trajkov or destroy him, with various permutations therein, but I doubt you’re actually going to be swayed either way once you get there. Meeting Trajkov himself is deeply underwhelming (in a good way), because if you’ve been exploring and talking to NPCs then you probably know exactly what you’re going to do about him by the time you get to his chamber. If you’ve made it this far, no matter which path you took, you’re likely already powerful enough to put your plans into action.

Clicking this sentence will reveal endgame spoilers.

The

Geneforge games have always been political, but the struggles and separations of the Serviles on Sucia Island feel especially poignant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and political unrest in the United States over the past year. The land itself on Sucia has become sick due to the poorly managed containment procedures of the Shapers as they escaped the island, making it difficult to grow crops. It is dangerous to leave one’s village and scrounge for resources due to the rogue monsters coming from… somewhere, and even if the serviles knew where the source was they don’t have the tools or strength to shut it down.

The thing that’s sticking with me the most though is the repeated interactions where Serviles will ask you, a Shaper (the creator of their people) what you think is right. If you give them an honest opinion that conflicts with what they believe, they will reject it completely – even the speech from their god’s lips can not sway their convictions. It is easier to empathize with the Takers in 2021, those serviles who have been abandoned by their caretakers and guardians and in that absence have realized just how poorly they were being treated, now brimming with intent to destroy the system that abused them.

Mutagen adds a new theme about Serviles to the game – the inutile, a Servile-society term for a Servile that can’t work

right. Through my own lenses, the idea of the inutile seems a thinly-veiled metaphor for neurodivergence and queerness, and how those things intersect with the larger expectations of living in a capitalist society. Serviles have children the same way humans do, and sometimes Serviles come out non-”standard”, just like humans. Despite the sects’ developing ideologies about their interaction with Shapers, none of them can get away from the culture of work that was instilled in their very genes when they were first created. Any Servile that can’t work in the ways Serviles are

supposed to work is outcast, left for the wandering monsters of the island to take care of.

Some of the inutile you’ll meet outside of the Servile villages got obsessively fixated on the job their family line was originally tasked with, and sent out. Some of them don’t want a life of toil. A rare few are just uncontrollably violent. But most of them are totally reasonable people who disagreed with the fanatic philosophy they grew up in, and were forced out of society for it. I found that the inutiles were often kind, curious, and prepared to stand toe-to-toe with a Shaper bearing down at them. They were the actuality of the Awakened and Taker philosophies, existing independently from Shapers

and the societies fixated on Shapers.

The epilogue that plays based on your decisions after you leave the island includes a note about Thrackerzod, hinting that he may return in future remasters of the

Geneforge series. If those future remasters simply added the new UI, mechanics, and spells, I would probably be very content to pick them up. However, I hope future remasters add more responsive writing to the games, as

Mutagen was still plagued by the problem of NPCs that somehow know you’ve done something before you’ve come back to tell them you’ve done it, and yet have nothing particularly new to say about it. Dialogue trees are inconsistent in their accessibility – sometimes broaching a topic down one tree brings that topic to the main conversation panel, sometimes you have to go down that whole tree again just to ask a different question about that topic. Vogel’s writing is excellent, and I want more of it – and for it to flow a little more naturally.

Mutagen is an excellent updating and reimagining of a classic CRPG, with new story, new systems, and a much-needed update of the UI and graphics. The mysteries of Sucia Island, the thrill of unlocking powerful magics, and the danger around every corner make

Mutagen a gripping experience despite its methodical play. Any lover of CRPGs should play it – with some conditions.

If you’ve never played

Geneforge, this is the time. The game takes up all of a modern screen now, and the combat rework has made the game much more accessible without reducing the challenge. If you’ve tried

G1 in the past and couldn’t stomach the outdated UI and low resolution,

Mutagen has come to save you from a

Geneforgeless life. If you loved the original

Geneforge games,

Mutagen’s new systems provide a new way of experiencing the classic story and setting. If you loved the

story in

G1 but weren’t actually that excited by the way the game works,

Mutagen’s mechanical reworks probably aren’t different enough to make you love playing, and I’d suggest you pass.

Ultimately,

Mutagen is a brilliant example of what a remaster of a classic game can be. The mechanical reworks are intense, but don’t lose the heart of the original game. I look forward to playing

Mutagen again and making different choices, and I hope the remaster of

Geneforge 2 is in the near-ish future.