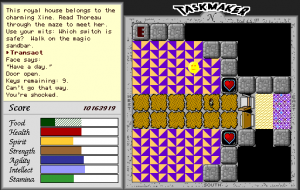

There’s a trick

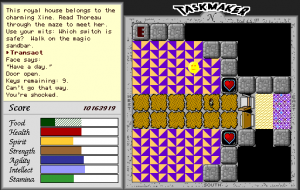

TaskMaker loves to pull where one tile in a wall looks slightly different than the others. It’s called a “passwall,” and if you spot one, you can walk through it into a hidden passage or shortcut.

TaskMaker doesn’t treat them like secrets. They’re part of the tutorial, and sometimes they’re the only way to advance through the game.

Secrets like this are the language of David Cook’s eccentric role-playing game

TaskMaker.

According to an Easter egg that explains the development of the game,

TaskMaker was loosely inspired by a tabletop role-playing game that creator David Cook ran with his friends back in 1982. He adapted the basic idea into a computer game six years later for his software company Storm Impact, working on it part-time at night over the course of a year. Very little remains from the original tabletop concept apart from, most notably, the king-like ruler known as the TaskMaker.

(Whenever you speak to the TaskMaker, the game announces “TaskMaker!” in a dramatic voice.

Please listen to the game say “TaskMaker!” so you can imagine this sound every time you read the word TaskMaker.)

You’ve traveled from faraway to enter into the TaskMaker’s employ to help him defeat evil. Of course, he ends up being a tyrant. At first, he assigns you benign errands, like retrieving his favorite chessboard, and he bestows gifts upon you to celebrate your success. Then gradually he gives you terrible tasks like robbing the old king’s tomb. It becomes clear that you aren’t actually helping anyone. The TaskMaker is not only a violent despot but petty and vengeful: he orders you to kill the leader of a peaceful independent town and humiliate a nearby kingdom by stealing their coat of arms.

You don’t get much say in following the TaskMaker until near the very end, and as most of your tasks are solved by killing a parade of evil monsters, the game doesn’t quite earn its final, predictable twist when the TaskMaker gloats, “Rather than become your own person, you gladly followed my evil whims.” It does, however, act as a slight critique of the inherent tyranny of role-playing games with kings handing out quests, like Lord British in the

Ultima series. The world is better off without an errand boy enforcing the rule of an empire.

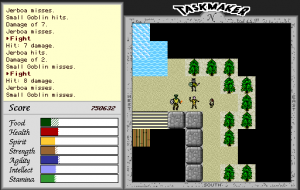

Sometimes the best way to deal with monsters is to hide behind a wall and recover

It’s not a satire or a parody of RPGs, exactly, more like a funhouse mirror amplification of their quirks. You fight goblins and golems, but you also fight angry lamps. The monsters generally seem to mean well even while they’re stabbing you to death, and given the chance to make peace by offering them a valuable item, they’d much rather talk to you about how much they love cream spinach. There are items like the rich ring, a piece of jewelry that gets you drunk, and

a townsperson named Man in the Moon who looks like

that creepy McDonald’s mascot Mac Tonight. We know in our hearts that the TaskMaker can never oppress the free spirit of Man in the Moon. Maybe he hates what he can’t understand.

The game avoids veering into a full-fledged comedy, just exaggerating the silliness that already exists here, in contrast to an adventure that can be dark and foreboding. The only gap in

TaskMaker‘s cleverness is its very literal, repetitive interpretation of role-playing game combat. It feels imaginatively constrained, perhaps out of an obligation to some sense of RPG dogma; for instance, the game gives your character separate traits for Intellect and Spirit without coming up with a meaningful difference between them. (To the developer’s credit, the sequel to

TaskMaker revised that.)

But

TaskMaker saves the most creative exaggeration for its oddly build towns and temples. Every village and dungeon is an interlocking nest of secret hallways, almost to the exclusion of anything else coherent about the setting. If the way forward isn’t hidden behind a passwall, it could be behind a locked door, a maze of teleporters, a trap floor, or a long snaking tunnel where the letters on the walls spell out literary messages – which, as absurd as that sounds, happens in three different locations.

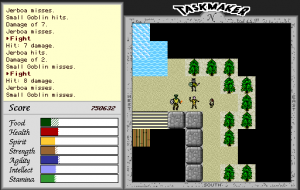

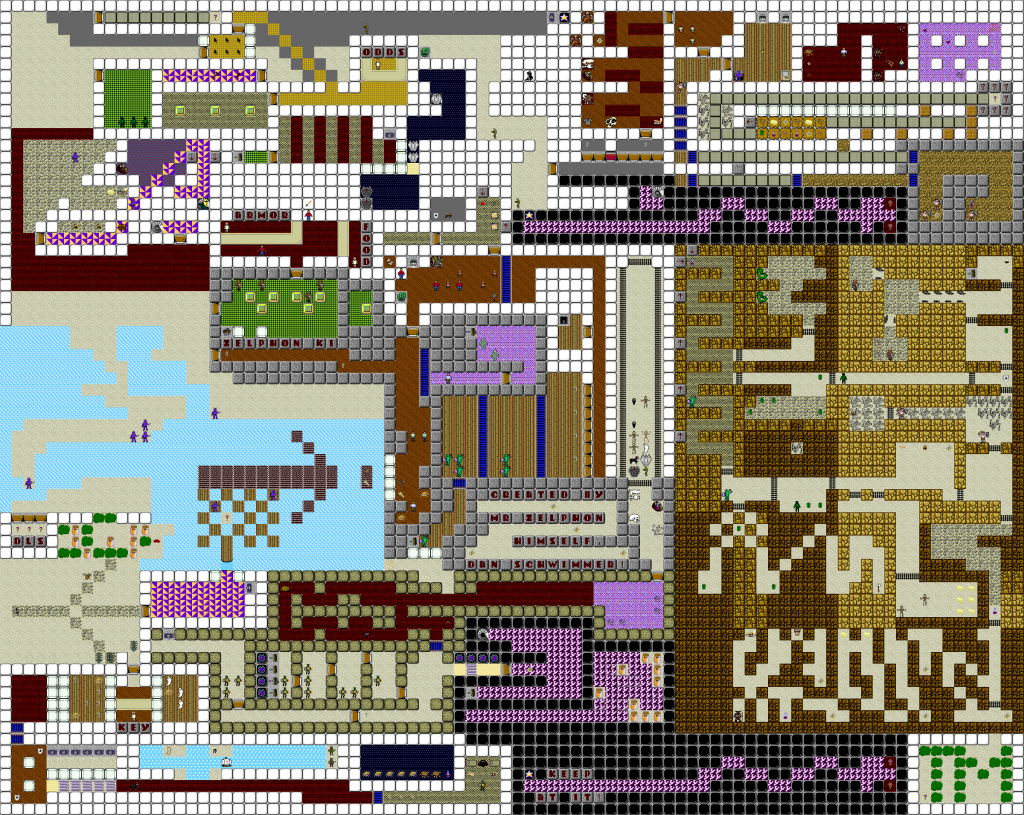

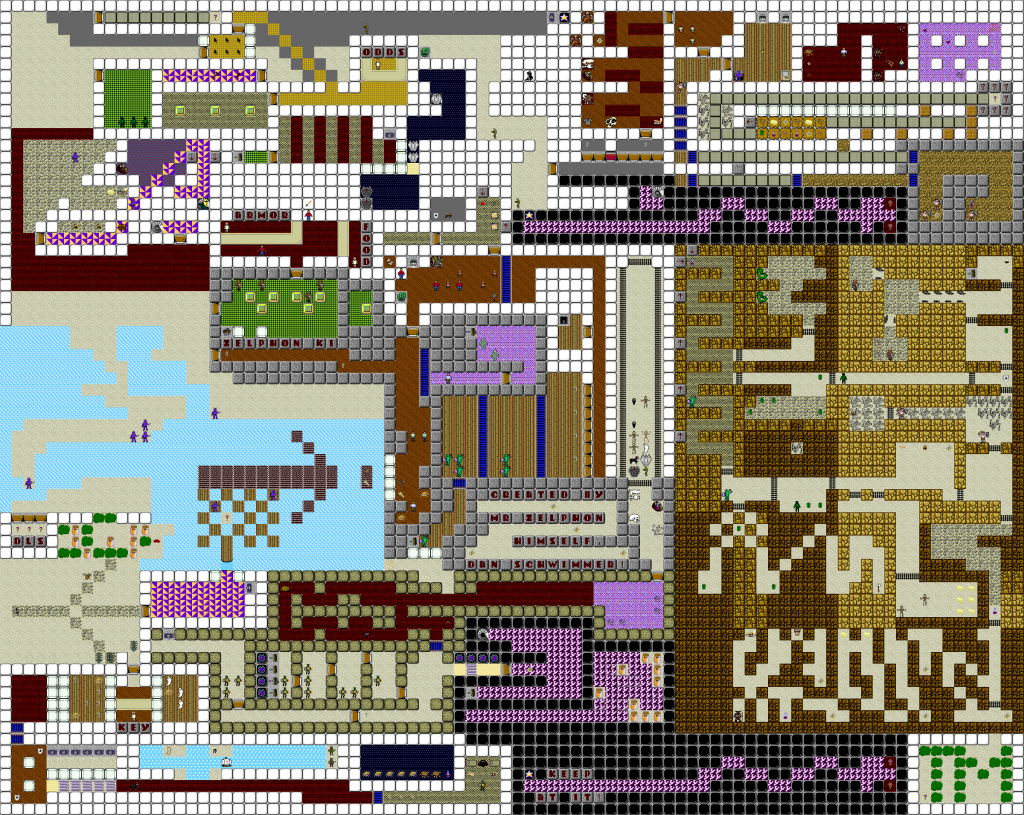

Here’s a closer look at one section that serves as a great example of this game. This is the fourth dungeon – the quest to steal a magic book from the Arbalest Catacombs, shown below:

The labyrinth of Arbalest Catacombs (click to enlarge)

The layout is terrifically intricate, switching themes and architectural styles between every room. These are catacombs, but they have an underground lake and an inconveniently located sandwich shop, which must get terrible business. (

TaskMaker was originally a black-and-white game redrawn in color, which may explain the strong profiles of tiles like the purple eagle-patterned TaskMaker floors.) The game never shows the full map like this; your vision is buffered by walls and doors, so you rarely see more than one area at a time. As you move between section and warp across regions the map, keeping track of where you are and where you’re going can be taxing. You’re always heading down further and deeper, farther away from any anchoring place you might remember.

That’s a perfect representation of

TaskMaker. Every location in this game is a densely packed, intersecting nightmare, unusual fountains and cities within cities, interspersed with orcs, gargoyles, and Crab-Claws to fight. The game hides surprises everywhere. There’s something unusual on the other side of every door and every teleporter, whether it’s a sword or a bag of marbles. You can even find treasure by rummaging through

literal piles of garbage.

Open the door, and… force fields! Where’s the heart switch?

TaskMaker encourages you to poke at its seams to an extent that verges on cheating. Some of the most powerful weapons in the game are kept in the backrooms of the TaskMaker’s castle, and although normally you have to wait until the end of the game to retrieve them, you could drink an Ethereal Potion, a rare item which lets you walk through certain walls, and sneak in through a single permeable tile in the back of the castle. You should definitely not be allowed to get the Vorpal Sword so early, but the game quietly leaves that door open in the back.

All this has the cumulative effect of feeling like you’ve exploited the game or gone somewhere you’re not supposed to. But it wants you to do that!

TaskMaker is so saturated in secret areas and sneaky backways that I still don’t know what its baseline for “normal” is. Beating the game felt like I got away with a crime.

When you finally overthrow the TaskMaker after a comically difficult battle, you inherit his powers. This is still not necessarily a happy ending for the world, but it opens a menu that grants you god-like abilities to go anywhere, to summon any object and character, and to change the tiles in the world itself. (I used this mode to capture the dungeon map!) When you have total omnipotence, it makes the eccentricities of

TaskMaker even more visible. Evidently, there’s a “10 meter cattle prod” weapon somewhere in the game. Was it tucked away in that huge tendril-like maze that I assumed was a dead end? On the other side of that lake you can only cross with random luck by using a magic scroll?

And furthermore, who started a mysterious sandwich shop in the

catacombs?

Download

TaskMaker and its sequel,

Tomb of the TaskMaker, are shareware. You can download the shareware copies of both games from

the Storm Impact website hosted by David Cook. Cook also still sells registration numbers for the games if you want to play the full versions.