JK: Are point and click games suited for telling stories, in your view?

Mark Yohalem: Only a certain kind of story works in point and click games. If you want to tell a story primarily about action and violence, or relationships and personal growth, I think it is a bad vehicle. For humorous stories or stories about introverted outsiders dealing primarily with machines/non-human obstacles, I think adventure games are fine. Ultimately, even though the genre has become known for its stories, I don’t think it’s particularly well suited to narrative for a variety of reasons. I do think adventures can have very compelling settings, memorable characters, interesting twists, powerful bursts of dialogue, etc. But I just don’t think that the pacing or nature of the gameplay is well suited to what we typically think of as good stories. Think about translating any well-regarded adventure game into a book or even movie – to the extent we can imagine it all, it is because we stitch together the un-interactive cut scenes while cutting out the gameplay. But if the story exists

in spite of the gameplay, then the game is not telling the story.

I say this despite loving adventure games and writing adventure game stories! But, ultimately, what I hope to provide my players is not me telling a story, but them experiencing an adventure. That’s something very different. Their minds will make a narrative of that adventure that is better than anything I could narrate through the medium, if that makes sense.

JK: What genre of games would you say are most well-suited to telling stories? I think of role-playing games (RPGs) like

Planescape: Torment, of Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs) such as

Xenogears and the

Suikoden series, and also of point and click games like

Primordia, Unavowed, Kathy Rain, and the

Broken Sword series, of how these games take players into new ‘virtual’ worlds where they’re able to immerse themselves in stories and characters, as they play and progress. Wonderful adventure games like

The Longest Journey and

Syberia also come to mind, as do

Coffee Talk (visual novel) and

Her Story (interactive film). What are your thoughts on digital games and storytelling, on games as interaction fiction (IF)?

Mark Yohalem: I’d say linear cinematic third-person action games are most conducive to telling stories. Think about the atrociousness of RPG novelizations. RPGs at least have more narrative “action” than adventure games, but the heart of the games is not where the

plot is happening. It’s where the

choice is happening. The moments we think of as “great story” in, say,

Planescape: Torment aren’t great

story. Rather, the choices (and consequences) are compelling. In a great RPG, we are

expressing a role through the game, rather than merely acting out someone else’s script and directions. For that to work, RPGs give us a series of encounters (often combat, but increasingly dialogues) in which we can resolve some conflict. These encounters are only loosely tied together (in a well-written RPG, they should all advance core themes and will often tie to other encounters)—they don’t form a linear story even if we experience them in sequence. “And then the hero talked to this guy. And then that lady. And then the dwarf over there,” and so on.

There is “story” in games, and games involve many traditional story-telling media within them (text to read, video to watch, narration to listen to, etc.). But what interactive games offer in comparison to traditional story-telling media is precisely our active participation. The games that offer the most rewarding narrative experiences are not necessarily the games telling the best stories; they are the games that permit our participation within the story. Adam Cadre, a developer of wonderful interactive fiction, wrote the following (Cadre, 2001) about

A Mind Forever Voyaging, generally regarded as having the best story of the classic games in that genre:

As for the story – well, had it been straight fiction, A Mind Forever Voyaging would count as about a fourth-rate dystopia: it’s no 1984, no The Man in the High Castle, not even a Brave New World. Had the author, Steve Meretzky, led me by the hand through the world he’d created – “Perry nervously walked through the zoo. He passed a sign that read MONKEY TORTURING: 2 PM IN THE PRIMATE CAGE.” – I probably would’ve groaned and felt as though I were being lectured at. But this is IF. I chose to walk through the zoo; I chose to look at the sign. What could have been ham-handed magically becomes a chilling detail, delivered with a light touch.

Cadre knows whereof he speaks: his own most famous work, Photopia, was immensely moving for me; his one novel,

Ready, Okay!, “felt as though I were being lectured at.”

Thus, what I would say is that even if a linear cinematic third-person shooter is better at

telling stories, the magic that Cadre is describing is conjured best by other genres.

JK: On the potential of games to be progressive and educational?

Mark Yohalem: Of course, it depends on the game.

The Oregon Trail was progressive and educational.

Duke Nukem was neither progressive nor educational (at least in the sense a school would use “educational”). Neither game is perfect, but both brought me great pleasure. I am totally unable to nose-count individual games or generalize about the medium as a whole. But for me, and many others I think, there is a humanist quality to gaming as a

hobby that deserves mention: namely, that the interaction of the Internet and gaming means that, through discussions or online play, one’s enjoyment of a game inevitably exposes him or her to other folks from around the world who

also enjoy the game. This leads to direct interactions that introduce strangers and bring them together. But it also leads to the indirect sense of universality: when I and a Polish player can both adore some obscure game (say,

Dark Sun: Shattered Lands) that is proof that there is a common quality

in us that is resonating with that game.

In developing

Primordia, I’ve seen how it attracts as disparate players as you could imagine, on every axis – people from every populated continent and dozens of countries, the far extremes of the political spectrum, devout believers in several religions as well as committed atheists and everything in between, hardcore and casual gamers, people of all gender identities and sexual orientations, the very old (one octogenarian!) to the very young (including my girls when they were still toddlers).

This is hardly unique to

Primordia. And, to be fair, it is not unique to games. But there is something

distinctive about games in my mind. For when we play a game, we put on, for a time, another self—that of the game’s protagonist. And, as it turns out, that self is a well-worn suit that fits comfortably on a wide sampling of humanity. So perhaps we are not made so differently after all.

JK: How do you view the field of game criticism and analysis?

Mark Yohalem: I think there has always been a great community around computer and video games who discuss and dissect the games in ways that go far beyond simply “reviewing” them – it’s one of the special things about this pastime. In some ways, the growing body of “academic” game criticism and analysis could be seen as a subset or outgrowth of that long standing practice, but there are a couple of things about it that give me some gentle misgivings.

UseNet threads on rec.games.video.nintendo (and their successors in various forms over the years) may have been parochial and oftentimes sophomoric. But the flipside of “parochial” is that they were indigenous and the flipside of “sophomoric” is that they grew from the ground up. That is to say, these were instances of players using their experience with games to distill theory from practical know-how.

While quite a bit of serious game criticism and analysis still fits within that mold – for instance, when Emily Short writes about narrative design, she does so from the position of a player and a developer of interactive fiction as much as from the position of an academic theorist – some of it is more anthropological. People writing about games from the outside, based not on their own experience with games, but on their observations of others. As ridiculous and awful as the hurly burly of message board flame-wars and fanboying can sometimes be, I suspect that it has more direct impact on how games are actually being developed.

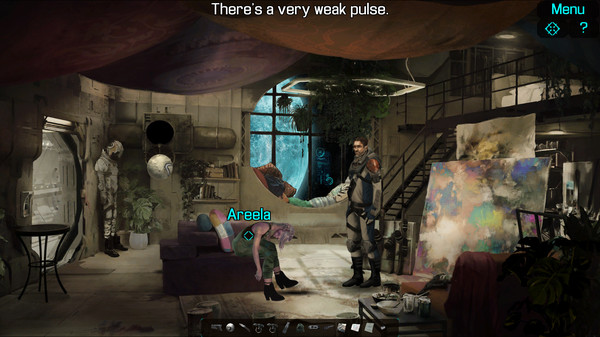

I guess the last thing I will say is that I think there is a disconnect between how game reviewers play and appreciate games and players play and appreciate games. Of course, I’m really biased here:

Primordia did rather poorly with “respected” professional reviewers (72% on Metacritic) while doing spectacularly well among players (bouncing between 98% and 97% positive on Steam, with over 2000 reviews, 4.7 and 4.8 stars on GOG, etc.). I don’t think this is just sour grapes, though. Professional reviewers, particularly when they’re dealing with indie games, have an imperative to get through the game quickly to move onto the next thing, so they inevitably will engage more superficially and get frustrated when the game prevents them from moving onward. Thus, an RPG with a really complex ruleset and challenging combat, or an adventure game with lots of tricky puzzles, might be really appealing to players who want to dig in, but fairly annoying to reviewers who want to be able to finish the game, evaluate it, and move on with things. By contrast, a game that is short, quirky, and pretty –or has spectacular technology behind it – will be a wonderful break from the grind for a reviewer, but might be less interesting to a player.

For that reason, I tend to find retrospectives, or “features,” more interesting than reviews, though of course I’m programmed to care about review scores just like everybody else is.

JK: Your thoughts on the popularity of point and click games?

Mark Yohalem: I think that in the 1980s and early 1990s, adventure games represented the high water mark of audiovisuals and narratives in PC gaming. For that reason, they were able to attract (and then train) a very broad group of players. Today, adventure games sound and look fine, but they’re not remotely at the level of a

Grand Theft Auto or

Modern Warfare or

Elder Scrolls title. And even adventure game developers have spent the last 20+ years publicly lecturing potential players that adventure games stink from a gameplay standpoint. No surprise that the tent has gotten much smaller as a result.

I also think that, generally, people today don’t grow up tinkering, experimenting, and puzzle-solving the way people did in earlier generations.

The generation that grew up on Apple IIc computers and the generation that grew up on Apple iPhones come to computer games with very different expectations of what it should be like to interact with a machine.

If you expect things to largely take care of themselves, and call an expert when they don’t, classic adventure games will feel “wrong,” “un-fun,” or overly demanding. But if hard knocks taught you that “mastery”

over a machine in the sense of “authority” exists only when you possess “mastery”

of the machine in the sense of “possession of great skill or technique,” then the demands of classic adventure games feel natural and appropriate.

This cultural shift is not a reason to eschew the defining feature of adventure games. Instead, it’s a clarion call to re-emphasize traditional puzzles. The genius of games is that they can let us partake in things that are impossible for us in real life – and sometimes make those impossible things possible.

I’ve watched my own daughters use the eccentric, ridiculous mentality of an adventure game player to discover in real life that the usefulness of a tool is not limited to the use for which it was made, that seemingly insurmountable obstacles sometimes have lateral bypasses, and that there are amazing parts all around us that can be cobbled together into delightful, unexpected wholes.

My kids might be better off if they’d learned those lessons in shop classes or by camping in the woods or from fiddling with the transmission on a car, but in the absence of learning by doing in real life, we can all at least develop the

aspiration or

anticipation of doing in reality by practicing in fantasy.

JK: On the importance of art within adventure games, and on artist Victor Pflug’s work on

Primordia?

Mark Yohalem: I think adventure games historically were at the cutting edge of visuals, not just in terms of technology but also in terms of aesthetics. There are obvious examples of spectacular beauty, from EGA games like

Loom or

King’s Quest IV (especially the day-night cycle for Tamir), to VGA games like

The Legend of Kyrandia II and

Simon the Sorcerer II and

Space Quest V, from cel animated SVGA games like

Curse of Monkey Island and

King’s Quest VII and

The Whispered World, to even FMV games like

Phantasmagoria and

Under a Killing Moon, to games with utterly unique looks such as

Grim Fandango or

Machinarium. It’s actually hard for me to think of any genre with art that is at once so diverse and so beautiful.

That tradition is carried on by indie adventure games today. Look at

Paradigm,

Dropsy,

STASIS,

Gibbous, and

Theropods – they’re all point-and-click adventures made by tiny teams, they look nothing alike, and they are all breathtakingly beautiful.

I guess you can ask, “Well, there are a lot of beautiful adventure games, but is that beauty really ‘important’ to adventure games?” – which seems to be your question. In some sense, it’s not important. After all, there are also adventure games that are quite ugly but also quite good

(Maniac Mansion, for instance) and interactive fiction adventures with no art at all that are magnificently evocative (

Photopia, for instance). But the additive value of beauty is really not quantifiable. It clearly has long been a hallmark of the genre. I suppose you can make an ugly cathedral (I’ve seen a few) and people can still practice faith and find hope inside, but that doesn’t disprove or even discount the importance of the otherworldly beauty of light and weightless that other cathedrals offer. So I’d say that beautiful art is very important to adventure games, even if not necessary.

As for Vic’s art, I think it is a shining part of that proud tradition – his work is instantly recognizable as

his (even if people don’t know who he is!), and while it is consistent with the design language of the 1990s, it has its own beautiful dialect. Vic’s characters are imbued with such personality and his backgrounds with such a richness of history, that they do much of the storytelling for me. One thing in particular that I love about his art is their Romantic quality – the way in which they take something beautiful, depict it in ruins or decay, and show how the process of decay actually reveals more that’s beautiful about it, the way that a burst pocket-watch reveals its inner workings or a weathered castle comes to peace with the countryside rather than dominating it or an old scholar’s face shows the wisdom that he’s earned. My favorite example of that in

Primordia is the interior of the courthouse, but that may just be because I’m a sentimental lawyer.

Vic’s art and my writing seem to work well together because both of us are, by coincidence, interested in the overlapping gray area between life and machine, beauty and horror – when I’m writing about robots dreaming of being humans or humans being reduced to what Chaplin called “machine men” in

The Great Dictator, Vic is painting machines with organic lines and organisms with mechanical parts. The ambience I want to capture in my stories is dark but hopeful, and I think Vic’s characters and settings are perfect for that. His people (and I include the robots in this) are often ugly and sad but still brimming with personality and humanity, and his scenes inevitably show a world where people built with care and have worked hard to keep things from crumbling.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)