Introduction

There's a good chance you know Obsidian Entertainment's Josh Sawyer as the lead designer on Fallout: New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity. But if you've been following the man's career, you might also know him as a bit of a history buff.

As such, it's no surprise that following Microsoft's acquisition of Obsidian, which resulted in greater freedom to experiment with more unorthodox projects, he jumped on the opportunity to direct a very much historical title in Pentiment.

The game itself is described as a narrative-driven adventure focusing on character development, heavily stylized art, and choice-driven storytelling in early 16th-century Bavaria. And with it being the latest Josh Sawyer production, we simply had to check it out.

All the World's a Game

Pentiment, the game's title, is derived from pentimento, a not exactly commonly used word defined as "a reappearance in a painting of an original drawn or painted element which was eventually painted over by the artist."

As far as titles go, this one is surprisingly apt, since the game's themes all revolve around this idea of old and long-since-buried things reemerging on the surface and wreaking all sorts of havoc.

The title makes sense if we look at the game's central decades-spanning mystery surrounding a series of murders in Tassing, a fictional Bavarian town, and the Kiersau abbey neighboring it.

It makes sense when we start delving into Tassing's history which stretches all the way from pre-Roman times and to around the invention of the printing press when the latter starts to gradually push the abbey's renowned book-writing scriptorium into irrelevance.

It also makes sense once we involve ourselves in the lives of Tassing's commoners and get a chance to watch generations change, children grow up and older people pass away or become progressively crankier.

And it even makes sense on a personal level for our protagonist Andreas Maler, initially a young painter with a lot to look forward to in life, but eventually a man with plenty of regrets and things he wouldn't mind forgetting.

When it was originally revealed, Pentiment was positioned as a narrative RPG following in the footsteps of Disco Elysium. It was later rebranded into a narrative adventure. Games like Night in the Woods were mentioned among its inspirations. In fact, at some point, Pentiment makes a not-so-subtle nod to Dear Esther, a title you might know as a fairly prominent example of a "walking simulator."

And so, here we come to the rather tricky hurdle of defining what a game even is and whether Pentiment qualifies. Which is only slightly easier than defining what an RPG is.

It's generally accepted that for a piece of interactive fiction to be considered a game, it needs to have express or implied failure states. Pentiment doesn't go easy on us here, as it seems that even if you don't engage with the game in any way other than mindlessly clicking on its perpetually highlighted hotspots, eventually you'll end up solving its central mystery.

If all you care about is learning whodunit, then chances are you'll be disappointed by the lack of agency in figuring it out. However, if you engage with the game on its own terms, you'll soon realize that it's the journey, not the destination that matters here.

Throughout the game, Andreas, being an artist instead of a detective, will have to balance his crime-solving hobby with his professional duties at the abbey. And with Pentiment being set in the simpler times when people lived in communities and interacted with their neighbors on a regular basis, Andreas will also be building friendships and rivalries with the townsfolk.

And it's precisely those parts where you have plenty of room for failure. Once you become a part of Tassing, you'll be able to influence it in various, oftentimes unpredictable ways. Maybe you'll decide that you want to help out some family that's been kind to you or maybe you'll take it upon yourself to expose some crook. But making that happen can actually be quite tricky.

Moreover, it can be hard to predict how your actions will end up affecting Tassing and its inhabitants in the long run. And with the way the game is structured, you'll get plenty of opportunities to face the consequences of your choices.

On the more gamey side of things, this also results in a system where people remember their interactions with you, so when you have to pass a persuasion check with them, all your previous actions are taken into account along with your character's skills.

And the great thing about this is that you never know if and when you'll need to persuade any particular character, or what this check will be concerning, making it pretty much impossible to metagame your interactions, at least during your first playthrough. And this, in conjunction with the game's frequent autosave system, leads to organic playthroughs where chances are, you won't succeed at everything you do. And this makes Pentiment very much a game.

Another issue that may be preventing some from giving Pentiment a fair shot is its historical nature. It's very easy to look at a historical title and assume it wouldn't be very fun on account of its critical lack of ale-guzzling dwarves or fireball-flinging robe-wearing geriatrics.

A big exception to this in the realm of RPGs is Warhorse Studios' Kingdom Come: Deliverance which takes place in medieval Bohemia circa the 15th century. And it just so happens that the events of Pentiment transpire in roughly the same area about a hundred years in the future. So, in a way, what with these two games both being based on real history, Pentiment can be seen as a sort of continuation of Kingdom Come: Deliverance.

You'll get to see the changes in the way people lived, experience the increasing influence of the Renaissance period, and stumble upon frequent references to the events depicted or mentioned in Warhorse's open-world masterpiece. And that alone may very well be worth the price of admission.

The Devil in the Details

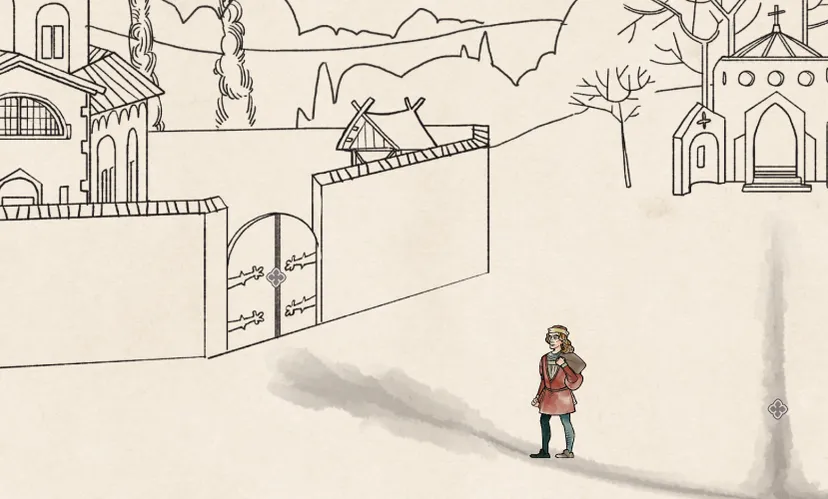

The game itself is presented as this medieval illuminated manuscript. Illuminated in this context refers to all the fancy borders and drawings on the margins, and not the act of shining a torch on a page.

As such, Pentiment's visuals are drawn in the rather odd but instantly recognizable style of those old manuscripts, with the game's action positioned as an illustration on a page. And if that alone wasn't enough, at any moment, you can press a button and pull the camera back to see more of a page with all the silly drawings of lopsided cats our ancestors loved so much.

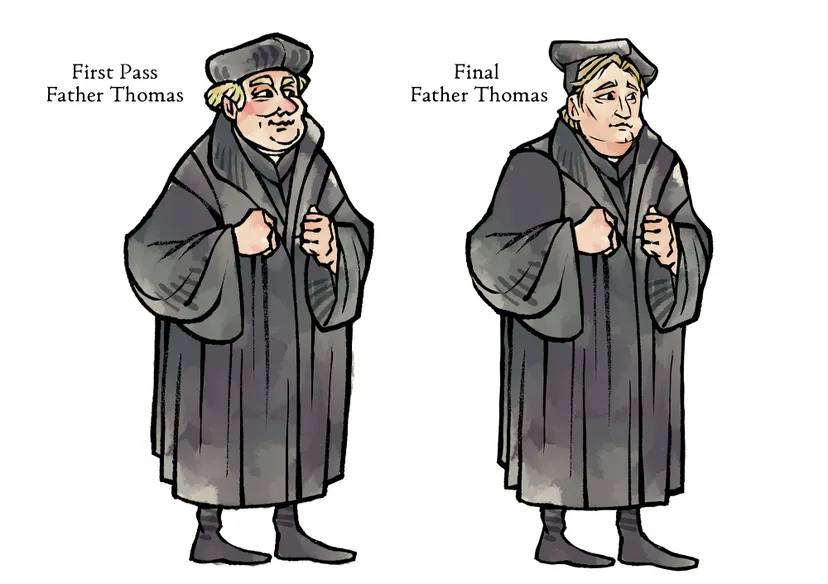

The game then takes this approach a step further and whenever you encounter an older character, they're drawn to look faded and less detailed than their younger counterparts. And whenever you get into a discussion about some book, like the Aeneid, your characters will step from their own pages and into the pages of the book in question and spend some time there.

Being positioned as a book, Pentiment is separated into three acts. The first act deals with a murder of a nobleman and the ripples it sends through the community. The second takes place seven years later and revolves around the growing rift between Tassing and the abbey. And finally, the third advances the clock a whopping eighteen years and delves into the history of Tassing. The later acts are punctuated with elaborate murders as well, but there they serve more of a supporting role to the bigger story.

The third act also lets you play as a new character, which works more than it doesn't. So even though this change happens a touch too abruptly and could probably have been executed better, it also has some really clever moments where you'll be examining the same objects you did as Andreas, but you'll get a completely different perspective on them. And that balances out some shaky developments and a rather forced resolution of the whole murder plot.

In general, the game's first act is the most expansive and full of options. In fact, at first, it may feel overwhelming with all the characters it keeps introducing and all the places you can visit and investigate. But then, the following acts feel significantly more linear.

But in a way, this also makes thematic sense, because, during the game's early stages, you're basically a stranger in Tassing. You're not familiar with the streets or the people living there. But once you get to know all these people and involve yourself in their lives, Tassing starts to feel smaller, cramped even.

Initially, though, you'll just be playing as a young artist trying to help his friend who's been accused of murder. If you've seen any police procedurals in your life, you probably know that to prove someone's guilt in a murder investigation you need to establish means, motive, and opportunity.

Not having the luxury of dozens of seasons of Law and Order at his disposal, Andreas takes a more cavalier approach to his investigation. He mostly focuses on the means and motive parts of the equation, while opportunity becomes but a distant afterthought for him.

This starts to make sense when you consider that Andreas is not the detective on the case, and he's actually forced to solve the murder before that detective arrives. As such, cross-referencing alibies and establishing corroborating statements is not something you'll get to do.

In fact, while you'll eventually get whoever was orchestrating the murders, you'll never know for sure if the people you accuse are the actual perpetrators. The way the game is set up, several people could have committed the murders, and a major aspect of the game is figuring out if you want to put the heat on whoever you feel is most likely to be the killer or someone whose guilt will affect the community in the least negative way.

This is further complicated by the fact that you can't physically follow all the leads at your disposal. Now, the game doesn't have an actual time limit to prod you along. Instead, each day you have is separated into several segments. And while most of your actions are free, certain legs of your investigation, like unearthing a grave or eavesdropping on a secret conversation, advance the clock several hours.

You usually have a decent number of options in how to spend your time, and so you'll be forced to decide if you want to continue digging in a certain direction, or instead spread your attention between all the suspects and then make an educated guess with what you've got.

Assisting you with all this will be an assortment of skills presented as backgrounds and cultural touchstones. These are generally determined by the places you've lived before your arrival in Tassing and the subjects you've studied over the years.

So, for example, being able to read French, on account of spending some time in France, will help you out in certain situations, but at the same time, it will preclude you from being able to decipher Italian texts.

By the looks of it, there aren't any random rolls or skill checks in the game. You either know something or you don't. And when it comes to persuasion, it's all about your skills as an orator and your previous interactions with the character you're trying to persuade.

Another notable thing about Pentiment is the way it presents its dialogue to you. The game has no voice acting of any kind, but instead, it elevates its text-based conversations to a new level.

This is very much welcome, as for years, RPG dialogues have not merely been stagnating, they've actually been regressing. We went from Planescape: Torment's complex dialogue trees to Mass Effect's dialogue wheel, and then to its simplified version in Fallout 4.

But then, games like Disco Elysium seem to have reminded people that there's still a lot that can be done with plain old text. And Pentiment is a great example of that.

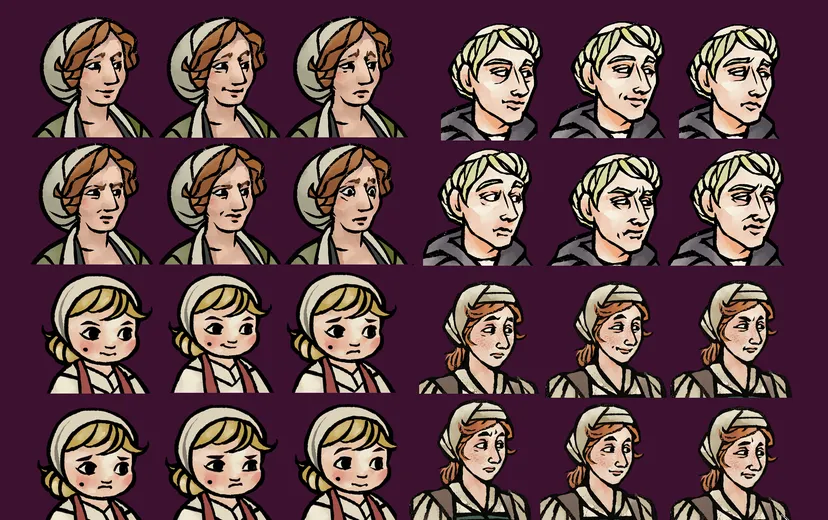

Keeping in tune with the game at large, whenever a character speaks in Pentiment, it's presented as a piece of parchment gradually being filled with writing. You get different fonts depending on who the character you're talking to is. Peasants and other barely literate people have their own simplistic scribbles, educated people write in a more legible way, monks impress you with their gothic font, while people working in the printing press business type out their words instead of writing them.

As that happens, you occasionally get typos that get fixed right before your eyes to simulate less-than-perfect speech. Parchments get covered in ink blots whenever a character is getting really steamed. And if you assume someone's level of education, but then realize you've misjudged them, the font they speak in will change from that point onward. It all absolutely oozes style and gives you a better feel for the characters than any voice acting.

This being an Obsidian title, it also uses the hyperlink system popularized by the likes of Pillars of Eternity and Tyranny. But here it's taken one step further. Whenever you click one of those links, an explanation of some term, person, or point of interest appears on the book's margins.

All of it looks really cool, but when taken in conjunction with the way Pentiment seems to know its own themes, its competent storytelling, and how everything in the game is set up and connected, you can't help but be impressed.

Sure, there's room for discussion about whether Pentiment is an actual game, but if we concede this point, then with the way it's executed, it may very well be the best Obsidian title since at least Fallout: New Vegas.

Technical Information

As we've already established, Pentiment's visuals are quite impressive. And with the way the game is structured, it's hard to decouple the visuals from the UI that's also presented in the same manuscript style. As such, while the menus can be a bit fiddly and slow to navigate, on account of them being stylized as bookmarked parts of a physical journal, just the fact that said journal is not a series of minimalistic transparent windows elevates it way above many of its contemporaries.

The game's audio is also a joy to listen to, be it the soundtrack, the background noises, or the sounds of a quill writing the game's dialogue. Now, by the looks of it, not everyone enjoyed the latter, and as a result, following a recent patch, you can now make the dialogue appear instantaneously.

In fact, the game has a decent number of accessibility options that pretty much everyone can enjoy, like scalable text size. The weird thing about Pentiment's options menu is that you can only access certain options once you've started a game. Another annoyance in that area is a lack of graphics options. You get a vague visual quality slider and that's it. And, this being a Unity Engine game, it's important to point out that there doesn't seem to be any way to enable VSync or limit the game's FPS number. Thankfully, Pentiment doesn't seem to suffer from Unity's propensity to turn your GPU into a jet engine, but it still would've been nice to have those options.

Another frequent Unity quirk - game saves taking forever - doesn't seem to be present here, and perhaps that's why you only get autosaves that happen during scene transitions and no quick or manual saves.

Being originally developed as an Xbox Game Pass title, Pentiment was designed with a controller in mind, and as a result of that the default keyboard and mouse control scheme is far from ideal. When keys like [ and ] see prominent use in your game, you must know you've messed up. Thankfully, the abovementioned patch also added a new option that allows you to navigate the menus using the mouse, and that makes things significantly more pleasant.

Finally, the game seems to be fairly well-polished and the only bugs worth mentioning include a rare couple of game logic lapses where characters go through certain conversations twice.

Conclusion

With its stylish presentation, tight and competently told story, and numerous advancements in the realm of video game dialogue, you would be remiss not to play Pentiment purely on account of it lacking the usual trappings of an RPG.

If you like historical settings, murder mysteries, and touching personal stories, then Pentiment is definitely a game for you regardless of how you want to classify it.