-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Gold Box SSI's Gold Box Series Thread

- Thread starter Saxon1974

- Start date

I only played the Forgotten Realms games back then and Treasures, but I plan to do Buck Rogers and Krynn at some points. I remember I wanted to do Buck Rogers years ago, the setting seemed a cool update to BR in general, but then I went ahead and read M. S. Murdock's Martian Wars trilogy, and that was so bad it soured me on playing the games. I actually want to read the Dragonlance novels for Krynn as well, but I wonder whether that is a good idea or not.

The first Buck Rogers game is fantastic! You will enjoy it.

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

I was thinking about this over the last couple of days. Some of the other better authors in the Forgotten Realms/Krynn settings:As Cael noted above, the writing by other authors ranged from mediocre to bad, and the average quality of TSR's fiction publishing tended to become worse over the years. The Krynn trilogy of Gold Box games does tie in to plot and setting of the early novels, so you might benefit from reading the original Chronicles trilogy and possibly the sequel Legends trilogy also written by Weis and Hickman, though if you find that you don't particularly care for the former then you might as well skip the latter and just read a plot summary.

Richard A Knaak - Legend of Huma

Douglas Niles - Maztica Trilogy, Moonshae Trilogy

R A Saltavore - Cleric Quintet, Driz'zt (of course)

Elaine Cunningham - Daughter of the Drow Trilogy

The others you can take or leave, it is really up to your taste, but I'd really give the Maztica trilogy a go. It is the Spanish-Waterdhavians conquering the Aztec-Nexalans in Mexico-Maztica :D

FYI, we have a thread about the FR novels: http://www.rpgcodex.net/forums/index.php?threads/forgotten-realms-novels.117754/

And about TSR novels: http://www.rpgcodex.net/forums/index.php?threads/tsr-novels.115449/

P.S. Elaine Cunningham is fucking cancer.

And about TSR novels: http://www.rpgcodex.net/forums/index.php?threads/tsr-novels.115449/

P.S. Elaine Cunningham is fucking cancer.

Last edited:

Grauken

Arcane

There are like a fuckton of FR novels, who has time for that. Just heard that the Dragonlance setting was more so than other settings strongly shaped by the novels, so I thought it would be a good idea.

Grauken

Arcane

So, Gateway was enjoyable. Not very hard. First few levels were best in terms of challenge, when I was scrounging for every gold piece and who to level up, but at level 3 to 4 I started to swim in money and since it's easy to rest almost everywhere, almost no fights that provided much of a challenge. Well, the final fight was challenging, regenerating boss my ass and all those annoying shambling mounds. Had to take the cowards option and let the undead take him out after 4 of my chars died and wasn't too enthusiastic to fight the low level mobs to reach him again. Still, its a fine game with lots of stuff to do. Probably do Treasures next, can't get all the nice loot I got in Gateway let go to waste

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

You need to abuse the stupid rule they put into all GB games that was never in the original PnP: Stinking Cloud. They make the save, they get a penalty of -2 to everything. They fail the save, they are paralysed. Instant kill on the next hit.So, Gateway was enjoyable. Not very hard. First few levels were best in terms of challenge, when I was scrounging for every gold piece and who to level up, but at level 3 to 4 I started to swim in money and since it's easy to rest almost everywhere, almost no fights that provided much of a challenge. Well, the final fight was challenging, regenerating boss my ass and all those annoying shambling mounds. Had to take the cowards option and let the undead take him out after 4 of my chars died and wasn't too enthusiastic to fight the low level mobs to reach him again. Still, its a fine game with lots of stuff to do. Probably do Treasures next, can't get all the nice loot I got in Gateway let go to waste

Stinking cloud was never that powerful, but in the GB games, it is the best spell you'll get for a very long time. Abused that to kill dragons, who are very vulnerable to it, for some reason.

Against the shambling mounds, the most effective way is to use the wand of defoliation. You can hit up to two mounds easy per use, and it takes away about half max health per use. I recall clearing out everything to the final boss. I just can't remember what items I was using. I seem to recall Ice Storms being flung around, but can't remember if it was this game or another. Those kill shamblers also.

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

Dragonlance was actually a homebrew setting that Tracy Hickman, Margaret Weis and their friends were using. Raistlin was actually one of the player characters who roll extremely badly for his Con stat, or so the story goes. They built the setting based on it, and that's why the first trilogy set there was so much better than the rest of the Dragonlance stuff.There are like a fuckton of FR novels, who has time for that. Just heard that the Dragonlance setting was more so than other settings strongly shaped by the novels, so I thought it would be a good idea.

Grauken

Arcane

I wish they made some Ravenloft/Planescape/Dark Sun Goldbox games. Could have been glorious

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

Dark Sun came too late for GB. They tried using an updated engine, but it never became big.I wish they made some Ravenloft/Planescape/Dark Sun Goldbox games. Could have been glorious

Ravenloft is difficult to GB. It is not really a combat oriented campaign setting, more of a horror and sneaking setting. You don't want the big guys noticing you or you're toast, and cutting a massive swath through their minions is almost certain to do that. Any if you ignore that, you'll have the fans up in arms about not following the setting.

Planescape is... weird. I am not sure if GB could convey the craziness that is Planescape. Part of Torment's draw was the way that engine could convey the (relatively) alien background. That is beyond GB's ability, I think.

Grauken

Arcane

Yeah, the 1st Dark Sun game was excellent, sadly the 2nd not so much. At least for Ravenloft there are some FRUA modules, so whenever I run out of Goldbox games I'll always can try these.

Incantatar

Cipher

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2012

- Messages

- 456

I just now discovered Gold Box Companion. http://personal.inet.fi/koti/jhirvonen/gbc/

That makes PoR a lot less tedious. Time to replay!

That makes PoR a lot less tedious. Time to replay!

ProphetSword

Arcane

I wish they made some Ravenloft/Planescape/Dark Sun Goldbox games. Could have been glorious

There are Unlimited Adventures modules set in these settings. Depending on the module and the designers, they might even be up to Gold Box standards.

There's some good work out there to be seen if you want to explore it from a lot of different settings:

Grauken

Arcane

Yeah, I plan to play some modules, but first I want to play all the Goldbox games I haven't yet, which is both Krynn and the 2x Buck Rogers one. Then probably take on the Realm, thought not all one after another, as I can see burning out on the engine that way easily.

Grauken

Arcane

As much as I enjoy playing Goldbox games, they have next to no or only terrible dungeon crawling. Obviously that was never the intention of these games in the first place, but it just struck me how bad they are at it when they try. Found a spinner in the cavern below waterdeep in treasures, and all I could think was this is probably the only spinner in the whole game. There was none in gateway. It's all about cities strung along a plot and tactical battles, which is fine and good, but I think they missed the chance in adding some good dungeons as well.

Grauken

Arcane

Yeah, those. I mean the engine clearly support most of the stuff you would expect in dungeon crawling, yet at most the existing dungeons are 1-level affairs that don't offer a lot of challenge or interesting level design or the usual stuff you find in a Wizardry games. I could see how the tactical battles at the frequency you fight in Wizardry could get exhausting, but I think the dungeons could have been somewhat more involved and clever designed and also with whole damn map not shown at the outset. I wonder who had the brilliant idea to show the whole map in almost all levels.

Area View is lame, unless it's a place the party is supposed to know.

As for dungeon design, I think things like spinners and such are more appropriate for more abstract games like blobbers.

Gold Box games are more about encounter design than level design and mapping challenges. But there are som fun maps like the Lighthouse in Dark Queen.

As for dungeon design, I think things like spinners and such are more appropriate for more abstract games like blobbers.

Gold Box games are more about encounter design than level design and mapping challenges. But there are som fun maps like the Lighthouse in Dark Queen.

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

Play the Krynn series. The Temple at Hawksbluff, for example, is about 4 floors. The lighthouse octavius mentioned is 12+ floors. Even the outposts in Champions is 2 levels.Yeah, those. I mean the engine clearly support most of the stuff you would expect in dungeon crawling, yet at most the existing dungeons are 1-level affairs that don't offer a lot of challenge or interesting level design or the usual stuff you find in a Wizardry games. I could see how the tactical battles at the frequency you fight in Wizardry could get exhausting, but I think the dungeons could have been somewhat more involved and clever designed and also with whole damn map not shown at the outset. I wonder who had the brilliant idea to show the whole map in almost all levels.

Dorateen

Arcane

I've always been fond of Yarash's pyramid on Sorcerer's Isle. Teleportation traps/navigation were more frequent in Gold Box dungeon design.

Also, the Red Tower of Marcus in Pools of Darkness is an enjoyable multi-level affair.

Also, the Red Tower of Marcus in Pools of Darkness is an enjoyable multi-level affair.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 100,857

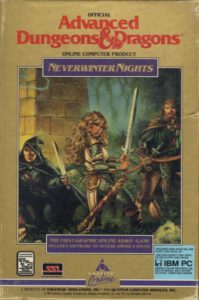

The Digital Antiquarian is doing a series on the history of multiplayer games. Here's his writeup on the original Neverwinter Nights: https://www.filfre.net/2017/12/game...e-web-part-3-the-persistent-multiplayer-crpg/

Another of the big single-player CRPG franchises, however, would make the leap — and not just to multiplayer but all way to a persistent virtual world like that of MUD or Island of Kesmai. Rather than running on the industry-leading CompuServe or even the gamer haven of GEnie, this pioneering effort would run on the nascent America Online.

Don Daglow was already a grizzled veteran of the games industry when he founded a development company called Beyond Software (no relation to the British company of the same name) in 1988. He had programmed games for fun on his university’s DEC PDP-10 in the 1970s, programmed them for money at Intellivision in the early 1980s, been one of the first producers at Electronic Arts in the mid-1980s — working on among other titles Thomas M. Disch’s flawed but fascinating text adventure Amnesia and the hugely lauded baseball simulation Earl Weaver Baseball — and finally came to spend some time in the same role at Brøderbund. At last, though, he had “got itchy” to do something that would be all his own. Beyond was his way of scratching that itch.

Thanks to Daglow’s industry connections, Beyond hit the ground running, establishing solid working relationships with two very disparate companies: Quantum Computer Services, who owned and operated America Online, and the boxed-game publisher SSI. Daglow actually signed on with the former the day after forming his company, agreeing to develop some simple games for their young online service which would prove to be the very first Beyond games to see the light of day. Beyond’s relationship with the latter would lead to the publication of another big-name-endorsed baseball simulation: Tony La Russa’s Ultimate Baseball, which would sell an impressive 85,684 copies, thereby becoming SSI’s most successful game to date that wasn’t an entry in their series of licensed Dungeons & Dragons games.

As it happened, though, Beyond’s relationship with SSI also came to encompass that license in fairly short order. They contracted to create some new Dungeons & Dragons single-player CRPGs, using the popular but aging Gold Box engine which SSI had heretofore reserved for in-house titles; the Beyond games were seen by SSI as a sort of stopgap while their in-house staff devoted themselves to developing a next-generation CRPG engine. Beyond’s efforts on this front would result in a pair of titles, Gateway to the Savage Frontier and Treasures of the Savage Frontier, before the disappointing sales of the latter told both parties that the jig was well and truly up for the Gold Box engine.

By Don Daglow’s account, the first graphical multiplayer CRPG set in a persistent world was the product of a fortunate synergy between the work Beyond was doing for AOL and the work they were doing for SSI.

I realized that I was doing online games with AOL and I was doing Dungeons & Dragons games with SSI. Nobody had done a graphical massively-multiplayer online game yet. Several teams had tried, but nobody had succeeded in shipping one. I looked at that, and said, “Wait, I know how to do this because I understand how the Dungeons & Dragons system works on the one hand, and I understand how online works on the other.” I called up Steve Case [at AOL], and Joel Billings and Chuck Kroegel at SSI, and said, “If you guys want to give it a shot, I can give you a graphical MMO, and we can be the first to have it.”

The game was christened Neverwinter Nights. “Neverwinter” was the area of the Forgotten Realms campaign setting which TSR, makers of the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop RPG, had carved out for Beyond to set their games; the two single-player Savage Frontier games were also set in the region. The “Nights,” meanwhile, was a sly allusion to the fact that AOL — and thus this game — was only available on nights and weekends, when the nation’s telecommunications lines could be leased relatively cheaply.

Neverwinter Nights had to be purchased as a boxed game before players could start paying AOL’s connection fees to actually play it. It looked almost indistinguishable from any other Gold Box title on store shelves — unless one noticed the names of America Online and Quantum Computer Services in the fine print.

On the face of it, Neverwinter Nights was the ugliest of kludges. Beyond took SSI’s venerable Gold Box engine, which had never been designed to incorporate multiplayer capabilities, and grafted exactly those capabilities onto it. At first glance, the end result looked the same as any of the many other Gold Box titles, right down to the convoluted interface that had been designed before mice were standard equipment on most computers. But when you started to look closer, the differences started to show. The player now controlled just one character instead of a full party; parties were formed by multiple players coming together to undertake a quest. To facilitate organizing and socializing, a system for chatting with other players in the same map square had been added. And, in perhaps the trickiest and certainly the kludgiest piece of the whole endeavor, the turn-based Gold Box engine had been converted into a pseudo-real-time proposition that worked just well enough to make multiplayer play possible.

It made for a strange hybrid to say the least — one which Richard Bartle for one dismisses as “innovative yet flawed.” Yet somehow it worked. After launching the game in June of 1991 with a capacity of 100 simultaneous players, Beyond and AOL were soon forced by popular demand to raise this number to 500, thus making Neverwinter Nights the most populous virtual world to go online to date. And even at that, there were long lines of players during peak periods waiting for others to drop out of the game so they could get into it, paying AOL’s minute-by-minute connection fee just to stand in the queue.

While players and would-be players of online CRPGs had undoubtedly been dreaming of the graphics which Neverwinter Nights offered for a long time, smart design was perhaps equally important to the game’s long-term popularity. To an even greater degree than Island of Kesmai, Neverwinter Nights strove to provide a structure for play. Don Daglow had been interested in online gaming for a long time, had played just about all of what was available, and had gone into this project with a clear idea of exactly what sort of game he wanted Neverwinter Nights to be. It was emphasized from the get-go that this was not to be a game of direct player-versus-player conflict. In fact, Beyond went even Kesmai one better in this area, electing not just to ban such combat from certain parts of the game but to ban it entirely. Neverwinter Nights was rather to be a game of cooperation and friendly competition. Players would meet on the town’s central square, form themselves into adventuring parties, and be assigned quests by a town clerk — shades of the much-loved first Gold Box game, Pool of Radiance — to kill such-and-such a monster or recover such-and-such a treasure. Everyone in the party would then share equally in the experience and loot that resulted. Even death was treated relatively gently: characters would be revived in town minus all of the stuff they had been toting along with them, but wouldn’t lose the armor, weapons, and magic items they had actually been using — much less lose their lives permanently, as happened in MUD.

One player’s character has just cast feeblemind on another’s, rendering him “stupid.” This became a sadly typical sight in the game.

Beyond’s efforts to engender the right community spirit weren’t entirely successful; players did find ways to torment one another. While player characters couldn’t attack one another physically, they could cast spells at one another — a necessary capability if a party’s magic-using characters were to be able to cast “buffing” spells on the fighters before and during combat. A favorite tactic of the griefers was to cast the “feeblemind” spell several times in succession on the newbies’ characters, reducing their intelligence and wisdom scores to the rock bottom of 3, thus making them for all practical purposes useless. One could visit a temple to get this sort of thing undone, but that cost gold the newbies didn’t have. By most accounts, there was much more of this sort of willful assholery in Neverwinter Nights than there had been in Island of Kesmai, notwithstanding the even greater lengths Beyond had gone to prevent it. Perhaps it was somehow down to the fact that Neverwinter Nights was a graphical game — however crude the graphics were even by the standards of the game’s own time — that led to it attracting a greater percentage of such immature players.

Griefers aside, though, Neverwinter Nights had much to recommend it, as well as plenty of players happy to play it in the spirit Beyond had intended. Indeed, the devotion the game’s most hardcore players displayed remains legendary to this day. They formed themselves into guilds, using that very word for the first time to describe such aggregations. They held fairs, contests, performances, and the occasional wedding. And they started at least two newsletters to keep track of goings-on in Neverwinter. Some issues have been preserved by dedicated fans, allowing us today a glimpse into a community that was at least as much about socializing and role-playing as monster-bashing. The first issue of News of the Realm, for example, tells us that Cyric has just become a proud father in the real world; that Vulcan and Dramia have opened their own weapons shop in the game; that Cold Chill the notorious bandit has shocked everyone by recognizing the errors of his ways and becoming good; that the dwarves Nystramo and Krishara are soon to hold their wedding — or, as dwarves call it, their “Hearth Building.” Clearly there was a lot going on in Neverwinter.

The addition of graphics would ironically limit the lifespan of many an online game; while text is timeless, computer graphics, especially in the fast-evolving 1980s and 1990s, had a definite expiration date. Under the circumstances, Neverwinter Nights had a reasonably long run, remaining available for six years on AOL. Over the course of that period online life and computer games both changed almost beyond recognition. Already looking pretty long in the tooth when Neverwinter Nights made its debut in 1991, the Gold Box engine by 1997 was a positive antique.

Despite the game’s all-too-obvious age, AOL’s decision to shut it down in July of 1997 was greeted with outrage by its rabid fan base, some of whom still nurse a strong sense of grievance to this day. But exactly how large that fan base still was by 1997 is a little uncertain. The Neverwinter Nights community insisted (and continues to insist) that the game was as popular as ever, making the claim from uncertain provenance that AOL was still making good money from it. Richard Bartle makes the eye-popping claim today, also without attribution, that it was still bringing in fully $5 million per year. Yet the reality remains that this was an archaic MS-DOS game at a time when software in general had largely completed the migration to Windows. It was only getting more brittle as it fell further and further behind the times. Just two months after the plug was pulled on Neverwinter Nights, Ultima Online debuted, marking the beginning of the modern era of massively-multiplayer CRPGs as we’ve come to know them today. Neverwinter Nights would have made for a sad sight in any direct comparison with Ultima Online. It’s understandable that AOL, never an overly games-focused service to begin with, would want to get out while the getting was good.

Even in its heyday, when the land of Neverwinter was stuffed to its 500-player capacity every night and more players were lining up outside, its popularity was never all that great in the grand scheme of the games industry; that very capacity limit if nothing else saw to that. Nevertheless, its place in gaming lore as a storied pioneer was such that Interplay chose to revive the name in 2002 in the form of a freestanding boxed CRPG with multiplayer capabilities. That version of Neverwinter Nights was played by many, many times more people than the original — and yet it could never hope to rival its predecessor’s claim to historical importance.

The massively-multiplayer online CRPGs that would follow the original Neverwinter Nights would be slicker, faster, in some ways friendlier, but the differences would be of degree, not of kind. MUD, Island of Kesmai, and Neverwinter Nights between them had invented a genre, going a long way in the process toward showing any future designers who happened to be paying attention exactly what worked there and what didn’t. All that remained for their descendants to do was to popularize it, to make it easier and cheaper and more convenient to lose oneself in a shared virtual world of the fantastic.

Cael

Arcane

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2017

- Messages

- 22,670

Krynn series and Savage Frontier series.Which of the Gold Box games are worth a play, and how did they stand the test of time?

Krynn is level 1 to 40. The last game is definitely crazy with the set piece combats.

Savage Frontier is far lower level. You'd reach the level caps very easily, though. Fun unique magic items for its time.

They are not too bad, but bear in mind that Gold Box is less RP and more tactical combat.