Looking Back: why it's still worth bracing against the cold in Icewind Dale

Icewind Dale was Black Isle’s attempt to bash out a quick action RPG in Baldur's Gate's Infinity Engine. Because they were the studio who'd built Fallout, however, they failed miserably: accidentally making a coherent world of Faerun's northern wastes, and filling its dungeons with tangled networks of tactical battles.

It’s still one of the best mistakes you can play on the PC today.

On paper, Icewind Dale was certainly a less ambitious prospect than Baldur’s Gate. Where BioWare’s first RPG had stitched its isometric maps together into a patchwork open world, Black Isle designed a largely linear run through a set series of dungeons. The player would return between each escapade to the same town to restock on potions and buy new spell scrolls. And that was about it.

But Icewind Dale was the product of a development team enjoying themselves, and it showed. Though Dragon Age mimics its overhead tactical camera, Icewind Dale’s battles are superior - the kind of encounters only designers who know their combat engine inside-out can muster.

Black Isle had come straight from helping out on Baldur’s Gate, and knew what made its real-time implementation of D&D tick: it was fast and satisfying, enlivened by screen-shaking critical hits - but a thwack of the space bar paused the chaos and made it a thoughtful affair.

Trent Oster, the lead on Icewind Dale’s Enhanced Edition, describes the game’s battles as “combat puzzles”: scuffles with suicide skeleton warriors who explode in shards of ice when popped with a well-placed arrow; trolls who need to be finished off with fire damage; and the lizard priests backing them up, acting out complicated spellcasting routines that could scupper the player’s advance if left undealt with.

Last year’s Enhanced Edition comes with a Story Mode that’ll let you plough through these fights like so much snow, but on normal difficulty you’ll need to concentrate. Some areas recall Doom and its monster closets - trapping the party into situations beyond their comfort spells and formations and forcing them to work out a plan for survival.

The toughest battles are an exercise in intense micromanagement - prioritising enemies, interrupting spells, countering clouds of suffocating gas, and never letting your hand move more than an inch away from that space bar.

Changing enemy types and scenarios mean there’s no falling into a favoured technique either - the area-of-effect spells that cleared the room when you were level five can only do half the job at level ten.

Good preparation helps. A scripting system similar to that in the upcoming

Battlefleet Gothic: Armada allows players to customise the behaviour of each party member down to the smallest detail. Want your wizard to pull the cord on that self-destructive fireball once their health drops below ten percent? You can do that.

Icewind Dale’s fiction might have it that six adventurers roll up to a cave and spend a long night ridding the place of its pests, but the reality is much more methodical: many of its fights are designed with the intent that you be slaughtered in seconds, have a long think about how to counter the status effects you’ve been pummelled with, and return after reshuffling your spellbook.

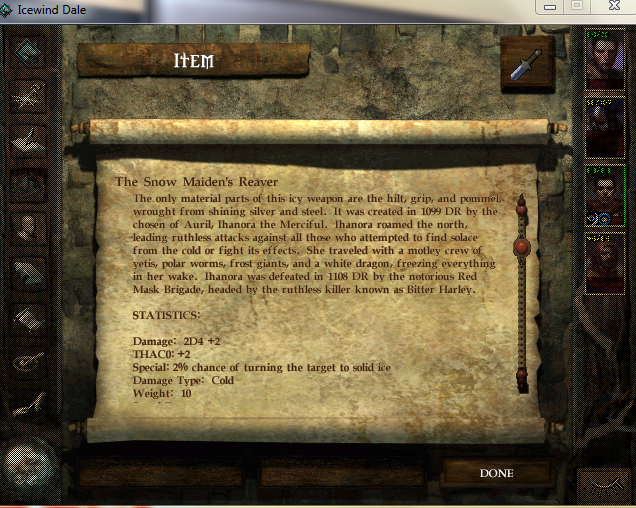

There’s a huge catalogue of D&D spells to pick from - far more than would sensibly be designed and implemented in the average digital RPG. It’s a tactician’s dream: for every tricky situation, there’s bound to be the perfect hex awaiting the player patient enough to trawl through the descriptions. Icewind Dale turns magic into the academic pursuit always implied by the bookkeeping and solitary lifestyle.

The dungeons are exquisitely gruelling. Perhaps more than in any other Western RPG, they capture the Tolkien-like process by which a party of near-strangers enters the maw of a mountainside and emerges, some days later, as an exhausted but hardened unit.

One dungeon in particular goes several levels down, uncloaking deeper and more dangerous depravities as it goes on and on. Once you step blinking back into the snow, it’s as if each goblin arrow has chipped away at your stoney adventurers, gradually revealing them for who they are. By the end of the game, you’ll have a walking, talking Testudo formation with stats and skills to covers for each others’ failings.

Two years later, Black Isle would release Icewind Dale II. If anything it was misnamed - taking its players away from the ice for what Avellone calls a “Forgotten Realms world tour”.

But this first game was about as grounded as RPGs get. While the plot does eventually spiral into an inter-dimensional grudge match, it never leaves the Ten Towns - the frozen region in the north of Faerun.

The sense of locality yields some wonderfully subtle world-building. The starting town alone, Easthaven, manages to pack subsistence, stoicism, religion and the stench of drying fish into an isometric drawing.

Later, in an extended bout of forensic storytelling, you get to pick through a Elven stronghold that fell tragically after the breakdown of its relationship with its dwarven allies. And then you'll traipse through the dwarven city and uncover their side of the story of how things went wrong. It’s like trudging through an epic poem punctuated by punch-ups with spectral orcs.

Icewind Dale also remains to my knowledge the only RPG in which you can have an argument with a skeleton about the problem of proactive foreign policy.

Tasked with finding the source of a warmth-quenching power that threatens to strangle civilisation in the Dale, you’re reduced to cracking open the crypts of known ancient evils in the area. More than once, your tenuous lines of inquiry end with a ticking off from an especially animated undead warrior about the audacity of storming into a tomb under false pretences. If its release date didn’t say different, I’d be convinced Icewind Dale was an allegory about the search for WMDs.

Despite the game’s overt combat focus, Black Isle clearly took role-playing very seriously in everything they did. Memorably, one map in the game can be turned from a dialogue hub to a wholly hostile area if you happen to have a paladin leading the party.

And the six-person character creation process is, while demanding, everything a D&D fan wants. It presents an opportunity not only for unstoppable combinations of multi-classed killers, but also high-concept parties. If you’ve an

imagination like Chris Avellone’s, perhaps all six will be red-robed wizards of Thay, unearthing powerful artefacts in the elven ruins around the Ten Towns. Or maybe the two bringing up the rear are slavers, and the rest their unwilling dragon-fodder.

There are dark patches in Icewind Dale’s otherwise gleaming white landscape. The idea of failing the dice roll to learn a spell and spending the rest of the game without it is likely to offend modern sensibilities. And there are at least a couple of cruel difficulty spikes: bosses only touchable with +3 weapons, and no in-game guide to explain as much. There’s no doubt that this is a game most-enjoyed by those who’ve already played another one, Baldur’s Gate. And that’s one time-consuming entry requirement.

But the new Enhanced Edition pulls in all the class and race options from Beamdog's other updated RPGs, turns once-broken multiplayer into convincing co-op, and blows up the game's maps to the highest resolutions - where the tangible cold of the Dale can be properly appreciated.

It’s a game that should have been simple, throwaway and quickly forgotten. But Black Isle simply didn’t have it in ‘em.