Congratulations you just described the classics.The character sprites are kinda derpy, the FX like fireballs etc look cheap as hell, and the backgrounds are so smudgy.

Try again.

Congratulations you just described the classics.The character sprites are kinda derpy, the FX like fireballs etc look cheap as hell, and the backgrounds are so smudgy.

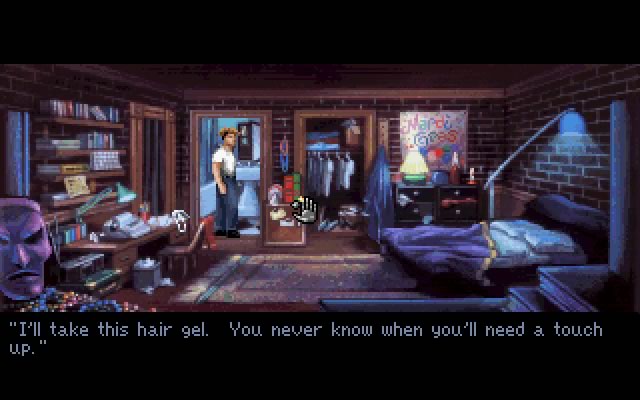

"Old adventure games had bad art" is the new "old adventure games consisted of nothing but illogical puzzles." The classics were (and are) beautiful.Congratulations you just described the classics.The character sprites are kinda derpy, the FX like fireballs etc look cheap as hell, and the backgrounds are so smudgy.

Well in that case I certainly wouldn't have loved Primordia much."Old adventure games had bad art" is the new "old adventure games consisted of nothing but illogical puzzles." The classics were (and are) beautiful.

reductive "technically true" statement

big words in big quotation marks that ultimately say nothing

Brooklyn or da Bronx, I forget which.wait what where is this

Me: Finally, at least some dissenting opinion.Matt: I played as an actor, and was … pleased but unwowed?

Me:Matt: I think it’s got a lot to do with the way I haven’t practiced much pointing and clicking. I’ve got fond memories of chatting with all the characters, but my most enduring one is agonising over how to heat up a cup of hot water.

Matt: I had a walkthrough open almost the entire time. My brain is not wired up for adventure in adventure games.

Me: Finally, at least some dissenting opinion.Matt: I played as an actor, and was … pleased but unwowed?

Me:Matt: I think it’s got a lot to do with the way I haven’t practiced much pointing and clicking. I’ve got fond memories of chatting with all the characters, but my most enduring one is agonising over how to heat up a cup of hot water.

Matt: I had a walkthrough open almost the entire time. My brain is not wired up for adventure in adventure games.

What Works And Why: Story structure in Unavowed

Learning lessons from episodic television

What Works And Why is a monthly column where Gunpoint and Heat Signature designer Tom Francis digs into the design of a game or mechanic and analyses what makes it good.

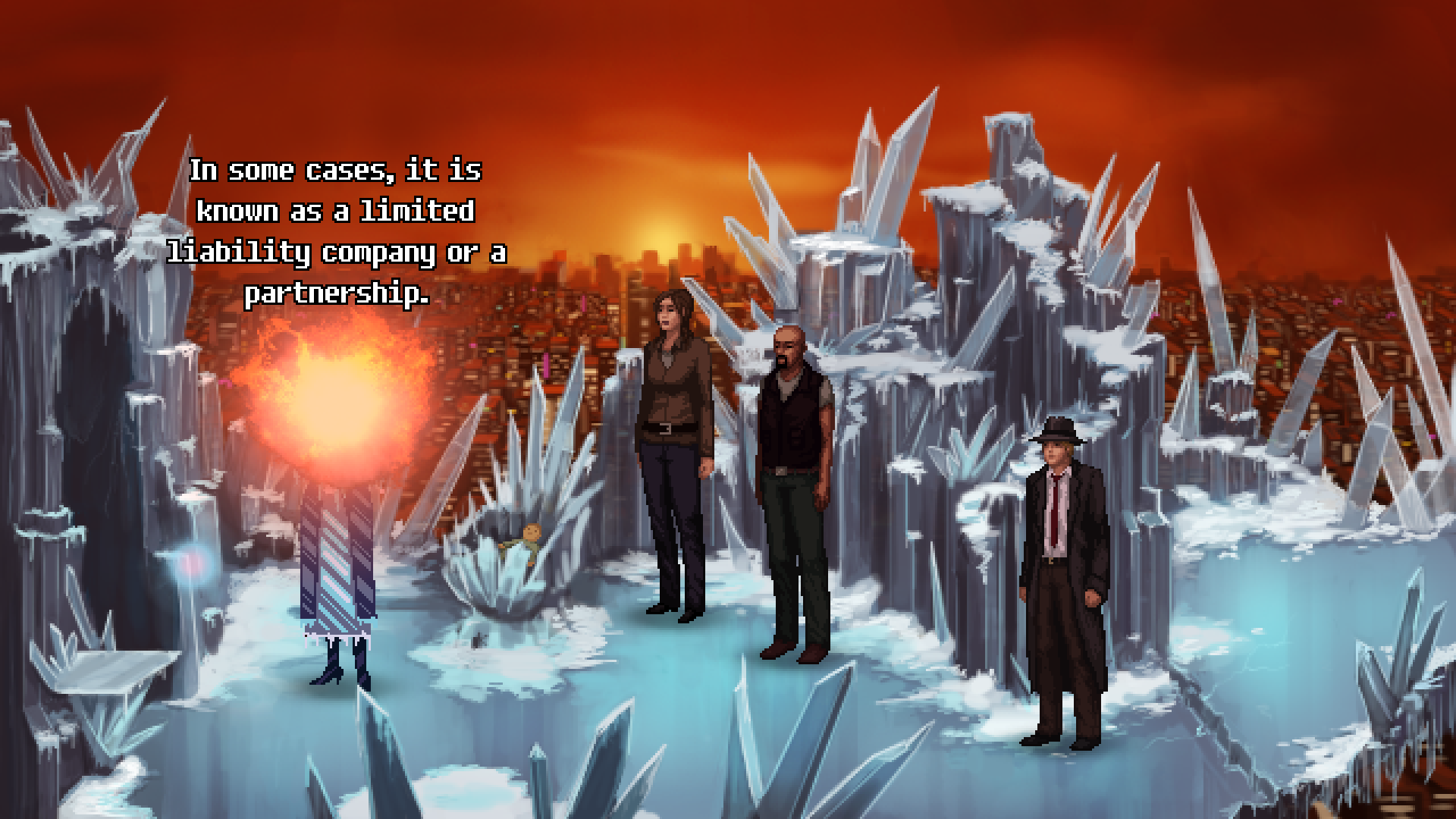

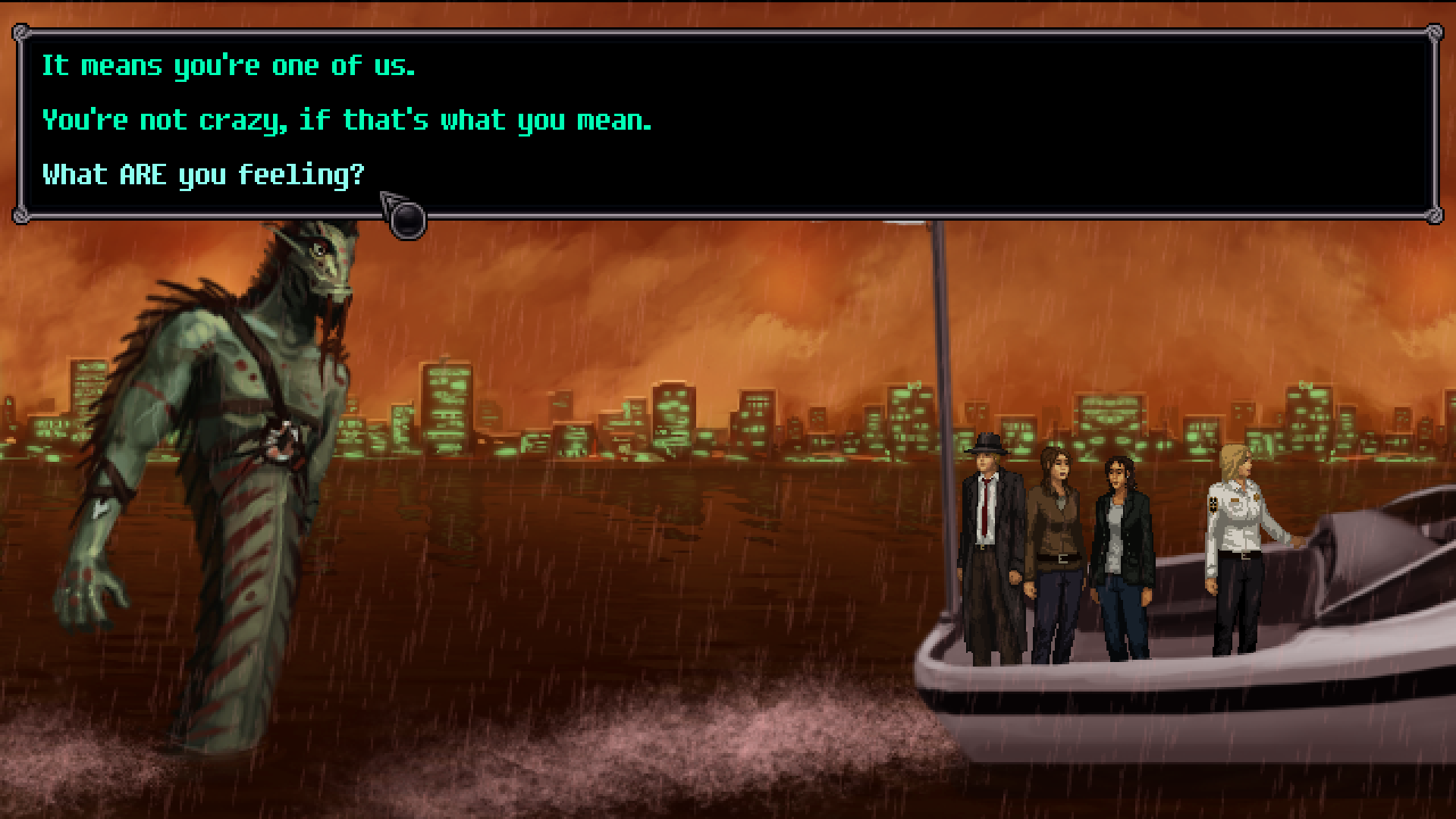

Unavowed is a point-and-click adventure from Wadjet Eye, who made the Blackwell series and The Shivah. I haven’t played those games, and I don’t usually like point-and-clicks. But Unavowed gripped me from start to finish. It has a few mechanical modernisations over other adventure games, but most of what sucked me in was just the story, and the way it’s told. It’s a glowing example of how to hook someone who doesn’t normally have the patience for the genre, and I want to pick apart how it does that. I’ll avoid spoilers beyond the basic premise.

You’ve been possessed. But you’re better now. You’re saved by a small team of supernatural investigators, whom you promptly join, and together you investigate yourself. Your former, demon-possessed self, whose actions you only remember in brief, involuntary flashbacks.

So the structure is this:

That loops repeats six or seven times, and it’s extremely compulsive. Why?

- Doing some mystical research back at base gives you leads on a few locations your possessed self visited

- You choose which one to go to, and who to take with you

- You have flashbacks to the terrible things you did there

- You piece together what happened, and who’s in trouble because of it

- You end up having to make some excruciatingly tough choice about how to resolve it

- You go home, talk about what happened, and pick a new lead to investigate next

It unfolds in chapters

Each cycle of this feels like a self-contained little adventure, with its own emotional climax, but each also reveals a bit more about the central mystery behind them all. That’s an addictive balance to strike, and a familiar one: it’s how most TV drama works.

The episodes feel like self-contained adventures because they each have their own arc. They start with their own mini-mystery: that flash of what your demon-self did, and the question of why. Mechanically, the way you investigate this is pretty rote: talk to everyone, then talk to everyone again to see if any of those chats unlocked new topics in the other ones. There are a few puzzles that expect you to really think about what’s going on – most of which I got stuck on – and the rest are simple, satisfying work.

All of what makes it work comes from the story: as you learn more about what happened, you’re able to confront people with this information, catch them in a lie, pressure them to own up. The tension and stakes escalate with your understanding of what happened, building towards a climax where you have all the facts, and you’re in a position to decide the fate of the person – or being – at the center of it all.

I remember a great game writing tip from interactive fiction writer Emily Short: if you really need the player to read a particular line of dialogue, put a choice on it. When they realise they actually have to make a decision, they automatically pay attention. The climaxes of Unavowed’s episodes turn this up to eleven: you’re being asked to make massive decisions, with an entire life or eternity in the balance. So you soak up everything you can about the situation, explore every dialogue option, and truly consider the characters and emotions in play. That has the the knock-on effect that you’re now much more engaged with the story in general.

There’s obviously a line to be drawn from here to BioWare’s games, which were an explicit inspiration for Unavowed. But in pure structure terms, Unavowed makes even better use of this pattern: without combat to slow it down, or the genre expections of an 80-hour journey to fulfill, the story powers along at an addictively brisk clip. You make about six of these life-altering decisions in the course of an 8-hour game.

It’s a good mystery

A good mystery has to be more than an unanswered question. I’ve written a bit about why Prey’s intro succeeds at this and Mankind Divided’s fails. Unavowed’s central mystery has some big things going for it:

It’s about you: in a mystery, this is an easy shortcut to get us to care a bit more. If we were investigating the actions of some guy called Neil, that’s of less immediate interest to me than finding out what my own character did while demonically possessed. Especially if I chose that character’s name, gender and profession, as you do at the start of Unavowed. It also gives a convenient reason for you to be fed intriguingly incomplete clues more or less whenever it’s narratively interesting for that to happen, through flashbacks. And it adds an interesting twist of guilt to your conversations with the survivors of your past self’s actions.

The question is ‘why’: trying to figure out who had done all these terrible things would be a lot less interesting (it was Neil). Figuring out how would be cool if they were somehow impossible, but in a supernatural setting nothing really is. Why, though, has inherent mystique. It implies there’s a hidden logic you’re not seeing, it teases that it might be possible to figure it out just by reasoning, and it’s always faintly sinister.

The clues are shown not told: the flashback conceit is convenient in another way – it lets you see what happened rather than being told about it second-hand. In fact, Unavowed is able to take this one stage further: you actually play the flashbacks, a nod to you sharing a body with the culprit. It’s a minor level of interactivity, but again it makes you pay so much more attention than if this was just someone’s long monologue recounting these events.

It starts with a bang

I won’t detail anything beyond the very first scene, but Unavowed is one of very few game stories to hook me in a few minutes flat. Its opening scene is a slightly hammy rooftop confrontation, but from there it jumps straight to a flashback that already reflects choices you just made, and escalates to shocking extremes with whiplash speed. It’s such a startling break that you half expect it to turn out to be a dream, but Unavowed earns its drama honestly, and you spend much of the game unravelling the consequences.

The dramatic start, intriguing mystery, and brisk episodic structure are things I’d love to see games learn from Unavowed. I don’t really need more games about demonic possession, but there are other ways to drip-feed clues, show instead of tell, and make a mystery feel personal.

So it's technically a bad game but you enjoy the delivery regarless

So it's technically a bad game but you enjoy the delivery regarless

If you put it like that I would say that it's a good interactive story, bad adventure game.

I didn't think it was possible for WEG to go even lower than the retardo-on-a-stick that was Shardlight, but by Jove, Unavowed has done it. Its plot and characters are comparably idiotic, sometimes I'd say even more so, although it still doesn't have anything on escaping GitMo by dropping an anvil on the head of a guard, but it's certainly a much worse fucking game. In fact, it's not a game. It's a walking sim with dialogues.

And the way that the only two things that are supposed to make this shit "stand out", i.e. "party composition" and "moral choices", don't matter absolutely fucking at all in the end is one of the biggest slaps in the face I've received from an ~interactive entertainment product~ (no, I'm not calling it a game, fuck you) in recent years. As I said in the LP thread for this garbage, Dave Gilbert might as well just personally jump out of the screen at the final showdown and spit in your eye.

I'm done with Wadjet Eye. None of the things they've released/published/whatever since 2012 that I played was worthwhile, in fact everything that they have thrown out in the last 6 years was nothing but nonsense and garbo.

I wish them all the best with their new audience.